This is one of the first hatchet jobs that I wrote for the Chicago Reader, which ran on October 2, 1987. — J.R.

FATAL ATTRACTION

no stars (Worthless)

Directed by Adrian Lyne

Written by James Dearden

With Michael Douglas, Glenn Close, Anne Archer, Ellen Hamilton Latzen, and Stuart Pankin.

“A profoundly uninteresting married yuppie lawyer (Michael Douglas) has a weekend affair with a profoundly uninteresting unmarried yuppie book editor (Glenn Close). The latter proves to be insane and makes the former’s life a living hell as soon as he ends the relationship, and the plot gradually turns into a sort of upscale remake of The Exorcist, with female sexuality (personified by Close) taking over the part of the Devil, and yuppie domesticity (personified by Douglas, wife Anne Archer, and daughter Ellen Hamilton Latzen) assuming the role of innocence. While billed as a romance and a thriller, the movie strictly qualifies as neither. The major emotions appealed to are prurient guilt, hatred, and dread; and with director Adrian Lyne shoving objects like a knife, a boiling pot, and an overflowing bath in the spectator’s face to signal that Something Awful’s Going to Happen, he can’t be expected to display any curiosity about the motivations of the spurned antiheroine, who eventually becomes, simply, an extraterrestrial robot killer. The perpetrator of the original screenplay is James Dearden, although apparently the minds of producers Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing, faced with dissatisfied preview audiences, are responsible for the totally dehumanized finale.”

The above capsule review can be found in Section Two of this paper. One reason for reproducing it here is to indicate all I would have wanted to say about this film had I seen it at an advance press screening three weeks ago. As luck would have it, I was away at the Toronto Festival of Festivals at the time, and caught up with the movie last week at the Biograph, by which time it was clearly the top grosser not only in Chicago, but also in most other major cities across the country. None of this has altered my opinion, but it has made me more curious about the film and its effect on audiences — enough so to make me brave the weekend crowds and see it a second time.

When The Exorcist came out in 1973, a good many critics were comparably perturbed about the film’s mass appeal, as well as by the peculiar behavior of audiences in relation to it. This was the period of Watergate and gas rationing. Some writers compared the lines at the gas pumps to the lines for the movie, and one of them, Elliott Stein, noted that few spectators seemed to be enjoying the film in any traditional way; he compared their alternately bored and avid responses to those of audiences at porn films, waiting restlessly for “the good parts.”

Some of this seems relevant to the odd tension I felt both times I attended Fatal Attraction, but it surely doesn’t suffice to account for the movie’s popularity. As was the case with The Exorcist, the audience of Fatal Attraction can be said to be primed for shocks and jolts, and some sense of guilt and anxiety clearly plays a role in establishing this nervous expectation. But The Exorcist had a little girl masturbating with a crucifix, howling obscenities, spewing out green bile, and rotating her head 360 degrees, among other highlights, while Fatal Attraction offers nothing much in the way of sex or violence that can’t readily be found elsewhere. At best there’s some slightly steamy sex when the lawyer and book editor make it next to a kitchen sink, and later inside a freight elevator; a little bit of gore when she attempts suicide by slashing her wrists, and boils his daughter’s pet rabbit in a pot, and jabs herself several times with a knife; and perhaps a bit of materialistic outrage when he finds that she’s poured acid over his car.

Yet if one can postulate some relationship between the appeal of The Exorcist and the feelings of disequilibrium caused by both Watergate and the energy crisis, it seems no less plausible to link the popularity of Fatal Attraction to the fear and moral confusion brought about jointly by feminism and the AIDS epidemic. The sense of retribution connected to the hero’s weekend fling is so palpably present in the threat posed by his ex-lover that the movie can tap into undercurrents of public hysteria about both subjects without having to allude to them even obliquely, much less deal with them. Apart from the ex-lover’s diatribes about the hero’s selfishness, and her remarks, after becoming pregnant, about wanting to be a single parent — both of which may be seen as parodies of feminism, as the character’s mental illness becomes increasingly apparent — the movie keeps itself squeaky-clean as far as AIDS and feminism are concerned. But that doesn’t prevent it from milking to the utmost some of the baser emotions aroused by these issues.

To get a better idea of some of the things that Fatal Attraction is saying (and doing) to its audience, it may help to recall the last film that coproducers Stanley R. Jaffe and Sherry Lansing, both former studio chiefs, worked on together: Kramer vs. Kramer. A yuppie film avant la lettre, this drama about single parenting placed nearly all its empathy and interest in the father, Dustin Hoffman, while the absent mother — played by Meryl Streep just prior to her stardom — was mainly kept in the wings, emotionally as well as physically. The nuclear family of Fatal Attraction is certainly at the dead center of its values, as is amply demonstrated by the film’s final shot — a lingering caress of the camera over a framed portrait of father, mother, and daughter. But even though Beth (Anne Archer) and Ellen (Ellen Hamilton Latzen) figure importantly in the plot, the center of identification remains Dan (Michael Douglas) throughout. It is his anguish — Douglas clenching and unclenching his jaw muscles with the same masochistic frenzy we associate with his father, Kirk — that guides the storytelling, and the suffering of his family at the hands of his ex-lover mainly functions as a means for escalating his own anger and violence.

And how does Glenn Close’s character figure in this structure? Her name, Alex Forrest, provides the beginning of a clue: a man’s first name, and a last name suggesting a dense thicket in which a man might lose his way; put them together and you get a precise conflation of the two principal male fears regarding feminism — the phallic woman and female sexuality. It might seem slanted to identify female sexuality exclusively with this character, as I do in the capsule review quoted above, and not at all with Beth, a sexy and attractive woman in her own right. But the movie shoves us in that direction early on — while incidentally making an affair for Dan seem justifiable and desirable — by having him return home from walking the dog one night to find Beth in bed with Ellen.

A fuller notion of what the characters represent can be gleaned from the places where they live. When the film opens, the Gallagher family inhabits a comfortable apartment on Manhattan’s upper west side; before long they move to a house in a Westchester County suburb, and an entire scene with their friends is devoted to explaining what this means in terms of upward mobility. It is only after Alex invades this latter turf that the film assumes the full dimensions of a horror story (and Borkian nightmare), although it already comes close to this when Dan finds that she’s poured acid on his car — her first infringement on his precious property.

Alex, on the other hand, lives in a loft downtown in the meat-packing district, and a good deal of expressionist lighting and smoke is expended to make the most of all that this implies in mythic terms. (Remember After Hours?) The dinginess of her building and the infernal yellow lights on the street outside conspire to make her Lucifer even before her madness becomes fully apparent, while the further association of her character with rain doesn’t so much douse the hellish fumes as make them more vaporous. Whether Alex qualifies as a yuppie, as I claimed in the capsule review, is perhaps open to debate; but arguably, if she didn’t come across like one at the publishing party where Dan first meets her, he probably wouldn’t be interested.

Intriguingly enough, the most resounding commercial flop of the last couple months was a picture that took a reverse position toward Manhattan yuppies, including a lawyer hero. This was Madonna’s underrated comedy Who’s That Girl, which ridiculed most of the same values that Fatal Attraction treats as sacred. (The Rolls Royce convertible that was gradually trashed over the course of the movie was the occasion for euphoric sight gags, not teeth-gnashing and portentous music.) Whether this means that the fans of Fatal Attraction are all yuppies at heart is another matter; while the ideological thrust of the film is unmistakable, it would be much too facile to assume that the picture’s success is predicated on a simple endorsement of what the audience already thinks.

People, after all, go to movies for fun rather than sermons — one reason, perhaps, why the playful satire of Who’s That Girl wasn’t much appreciated — and it can’t be argued that Fatal Attraction preaches anything overtly. But all movies are dream scenarios of one kind or another, and part of what appears to be drawing people to this one is the heavy undertow of sexual guilt and anxiety that it exploits. The economic trappings are to some extent merely reflections of what is routinely expected from Hollywood, and they become more blatant here mainly because what the movie chooses to ignore — Alex’s mind and background (as opposed to her behavior) — throws them into high relief.

Reportedly, the ending originally shot for Fatal Attraction involved Alex committing suicide — a conclusion that would have made the film’s allusions to Madame Butterfly more functional — and the negative response to this in previews convinced the filmmakers to juice things up with some protracted bathroom mayhem, climaxed by Alex’s resurrection from the bathtub after being drowned by Dan. (Some critics have objected to this part of the film while praising the rest; speaking for myself, I was so bored and alienated by what preceded it that I was perversely grateful for this ludicrous over-the-top addition.) That this ending makes hash of most of the preceding story doesn’t seem to bother spectators much, because the logic of extra-added shocks is so well established by now in horror and s-f fare that it seems to have superseded the separate logics of story, character, and genre.

At one point, for example, the film briefly turns into a mystery, when Dan sneaks into Alex’s loft to search for something he can use against her (such as evidence that another man might be the father of her expected child). The only significant item he uncovers — a newspaper obituary of a man we assume was Alex’s father, which contradicts her earlier statement that her father is alive and well — is promptly forgotten by the movie, a red herring whose sole function appears to be its reiteration of the fact that Alex is capable of saying or doing anything. In any case, the abandonment of the mystery plot only confirms that the movie’s true focus depends on a complete indifference to Alex’s psychology; it is only as a grotesque cipher and a supernatural demon that she can contain the full measure of an audience’s loathing for the sexuality she represents.

Yet significantly, in line with last summer’s hit Aliens, it is another woman — Beth rather than Dan — who assumes the key macho role in the film’s two showstoppers, which elicited applause and cheers at both screenings I attended. The first occurs after Alex kills Ellen’s pet rabbit. Dan reveals the weekend fling to Beth in order to explain the tragedy, and, after she recovers from her hysterical response, he dials Alex on the phone to tell her that his wife now knows about their affair. He then hands the receiver over to Beth, who says, “This is Beth Gallagher. If you ever come near my family again, I’ll kill you” — a declaration that promptly brings the house down. In the final bloodbath Beth keeps her promise, and that brings on the second wave of cheers. In both cases, the general feeling is that the spirit of John Wayne lives on, in drag, and even if the Duke (or Duchess) couldn’t lick the Big C, you can bet that s/he can wipe out the twin menaces of AIDS and pushy women with one effective blast.

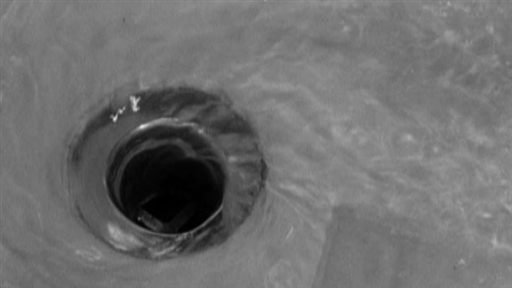

The movie’s ultimate logic, in other words, depends on external references to other movies rather than internal references to its own characters and plot. There’s even a reference to Psycho early in the bathroom scene — a lingering shot of water gurgling down the drain — to alert our salivary glands to the mayhem that’s on the way. Indeed, it is director Adrian Lyne’s penchant for telegraphing his punches well in advance — he pans slowly across a room to a telephone and then pauses, so we can all wait for it to ring — that keeps his audience in tow throughout. It’s a technique that he no doubt developed while turning out TV commercials in England (before going on to direct Foxes, Flashdance, and 9 1/2 Weeks), along with his method of turning up the sound track’s volume and adding bursts of caveman percussion during moments of rage and violence. This is the sort of thing Richard Schickel of Time must be talking about when he cites “Adrian Lyne’s elegantly unforced direction.”

Some other critics have compared this picture to a Hitchcock thriller. But while the Master of Suspense was certainly capable of working with an audience’s guilty feelings about illicit sex to generate tension, he always gave this tension a moral weight and a certain amount of moral ambiguity. If he shaped a narrative around a single character’s viewpoint, he wouldn’t deviate from that viewpoint for trivial reasons — as Fatal Attraction often does when it focuses on Alex alone, not to generate any further information about the character or plot, but merely to extend Dan’s glib incomprehension and hatred of her by other means, turning this into a universal principle so that it can also be experienced by the filmmakers and audience alike. Thanks to this determined ignorance and hostility, Fatal Attraction offers the same kind of fun as a lynching, with the similar satisfaction of a shared group endeavor when it’s over.