From the Chicago Reader, September 25, 1987. — J.R.

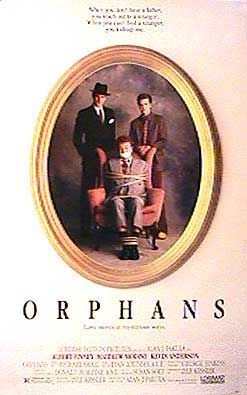

ORPHANS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Alan J. Pakula

Written by Lyle Kessler

With Albert Finney, Matthew Modine, Kevin Anderson, and John Kellogg.

Although the conventional Hollywood wisdom about adapting plays into movies is that plays should be “opened up,” the practical effect of this is often roughly equivalent to letting the air out of tires: the air may circulate more freely, but the wheels no longer turn. Fortunately Alan J. Pakula is a sensible enough man to recognize this danger, and the best thing that can be said about his movie of Orphans is that, by and large, he has allowed the original play to remain a play. Indeed, only by respecting the integrity of the original has he managed to adapt it into a fairly successful movie.

A contemporary play set in the present, Lyle Kessler’s Orphans has a distinctly uncontemporary, even old-fashioned flavor to it. Largely concerned with intense family relationships and feelings — between brothers, and between father and sons — it has virtually no traces of sadomasochism, which alone suffices to make it unfashionable as theater in this post-Pinter era. In a time when Sam Shepard’s laconic Marlboro ads are experienced as existentially authentic, and Wallace Shawn’s intricate lacerations and varieties of self-loathing are regarded as cathartic, Kessler’s primal depictions of brotherhood and fatherhood, without the usual smirking ironies, are simple and direct to the point of embarrassment.

Tricked out with key words like “encouragement” and “justice” that recur as pivotally as “pipe dream” in The Iceman Cometh and “mendacity” in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the language of Orphans evokes the last 40 years or so of American theater — the poetic effects that we associate with plays by Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, and William Inge, as well as the Method psychodramas that Elia Kazan would pound out of their familial tensions, polishing their simpler platitudes into bright, golden doorknobs waiting to be turned. “You can’t keep out the night,” says one of Kessler’s characters; “it comes in under the door, through the cracks.” For better and for worse, the resonance of such a line seems predicated on the fact that we’ve heard its near-equivalent countless times before.

The story centers on two orphaned brothers — the older one a petty thief named Treat (Matthew Modine), the younger one a recluse named Phillip (Kevin Anderson) — who inhabit a squalid, isolated house in Newark. Phillip, an apparently illiterate wild child who apparently has been confined to the house by Treat because of his apparent allergies, is totally dependent on his older brother, who relates to him alternately as a stern, protective, nurturing parent and as an older playmate in manic games of hide-and-seek.

Into this grubby and quasi-infantile world comes Harold (Albert Finney), an alcoholic and small-time Chicago gangster on the lam with an attache case full of money. Treat brings him to the house one night with the intention of kidnapping him for a ransom, but before long Harold has appointed himself the father of both orphans — first winning the confidence of Phillip, and then using his authority to win over the resisting Treat as well, under the pretext of hiring him as a bodyguard. (Having grown up in an orphanage himself, Harold fondly regards Treat as another “Dead End Kid.”) Before too long — an ellipsis of time serving as a break between acts in the original play — Harold’s powerful civilizing influence has transformed the house as well as the clothes and appearance of Treat and Phillip. By the time he is fatally gunned down by another gangster near the story’s end, he has convinced Phillip that he can strike out on his own — that he can leave the house without suffering an allergic attack — and in the process has obliged Treat to consider a different relationship to both his brother (who has already surreptitiously taught himself to read) and the world outside.

When the play first opened at a small Los Angeles theater called the Matrix, Harold didn’t die at the end; Kessler only arrived at this conclusion in the course of rewriting the ending some 25 times, before the play reopened here at Steppenwolf. From here the play went on to productions in New York and London, both of which included Kevin Anderson (who came from Steppenwolf), and the latter of which included Albert Finney (who also produced the English version). All versions of the play were confined to a single room in the house, and one imagines that the principal obstacle to making it into a movie was the conventional wisdom cited above–the impulse either to spread the action out over acres or to declare the work unadaptable.

Ironically, according to interviews, it was not Pakula but Kessler, the playwright, who originally wanted to “open up” the action in the movie adaptation. But while they have added a few scenes in exteriors, the claustrophobic interiority of the material remains the same. We follow Treat pulling off some street thefts at the beginning, and later see him outside the house negotiating with a fence to sell the stolen goods. We also see his initial encounters with Harold in a train station and a bar. But apart from a couple of other significant exceptions involving Phillip, Pakula keeps us inside the house for the remainder of the film, and it is possible that the play’s overall sense of confinement may even have been intensified through the use of close shots, camera movements, and extended takes.

By insisting on this approach, Pakula locks horns with a theoretical dilemma about the differences between stage and movie naturalism, and for all its considerable impact the film comes across in a peculiarly divided way. Considering the degree to which film tends to absorb all the other arts, we tend to forget that each art has developed at a different pace — abstraction in painting, for example, is considered less avant-garde today than abstraction in literature or film — and that what we mean by naturalism in the theater is hardly identical to what we mean by naturalism in movies. Because of this discrepancy, Orphans is paradoxically most persuasive when it is least naturalistic in conventional movie terms. In fact, it is only when it reaches for conventional movie naturalism that it registers as unconvincing, forced and false.

One example of this is the house itself. In ordinary movie terms, it is too disheveled before Harold’s arrival and too neat afterwards to be convincing. Yet one can easily accept these extremes as soon as one places an invisible proscenium arch, unconsciously or otherwise, over the proceedings. And the shock of the house’s transformation between the play’s two acts is handled no less effectively in the film with a simple shot transition. One is grateful for the avoidance here of a more “cinematic” device, such as a montage sequence that would have shown the gradual changes from squalor to domesticity — a sop to movie naturalism that would have eliminated the shock altogether.

What Pakula and Kessler have described as the “parable” or “fairy tale” aspect of the plot fits hand in glove with its theatricality. And thanks to the remarkable power of its three main actors, Orphans can work as a spellbinder even when it seems to be taking place on Mars. The capacity of theater to construct an alternate universe is vitally connected to the necessity that its action be confined and circumscribed like a formula in a test tube. To bring this universe in contact with what passes for “the real world”– that is, the everyday world that movies traditionally try to present — is to risk diluting the formula and breaking apart its components. One of the most interesting things about Pakula’s film is its willingness to take that risk without sacrificing the concentrated, hothouse intensity of the original. While some of Pakula’s decisions are unfortunate, the overall success of this screen adaptation is startling — a shotgun marriage that works.

It seems especially odd that Pakula should be the one to accomplish this. His major limitation as an artist is his tendency to sacrifice the integrity of an overall structure for the jazzy impact of localized effects. The same set of reflexes that led to his reductive adaptation of Sophie’s Choice–turning William Styron’s novel into a Meryl Streep vehicle, and riding roughshod over the delicate balances between the three major characters for the sake of shameless Oscar-mongering — have been less ruinous here, but they take their toll nevertheless. It is one thing for the camera to follow Treat in his excursions outside the house — his edgy relation to the outside world is, after all, important to his character — and quite another to follow Phillip, whose relation to the exterior world is a good deal more abstract and theoretical and needs to be entrusted exclusively to the spectator’s imagination. Pakula clearly understands this in principle, but when Phillip leaves the house for the first time, the director can’t resist the rhetorical flourish of an overhead shot showing the character’s rapturous enjoyment of his newly found freedom — a God’s-eye view that elevates the viewer’s superior position in relation to Phillip to the point of pomposity, and violates the sense of offscreen (or offstage) space that is so central to our perception of him.

As tacky as the effect is, along with a couple of related ones elsewhere, it is not nearly as disastrous as the sentimentalities and simplifications of Sophie’s Choice. Both films depend on a certain chemical balance between three leading characters, but the dynamics of each trio differ drastically. The beauty of Styron’s novel derives in part from the degree to which each character assumes his or her full meaning only in relation to the other two, like three simultaneous chords. The sentimentality of Stingo — like that of, say, Alyosha in The Brothers Karamazov — is bearable only in ironic counterpoint to the harsher and more immutable tragic destinies of the other characters, and Pakula fatally upsets this precarious balance by sentimentalizing all three of them.

Orphans, on the other hand, is more nearly a libretto for three actors than an autonomous text, and although the characters’ dependence on one another is important to the story, their separate identities are no less important. Treat and Phillip, unlike Sophie and Nathaniel, are virtually defined by their ability to change, while the more stolid identity of Harold is viewed less as tragic destiny than as a parental support and a sense of roots (his own orphaned childhood) that allows Phillip and Treat to grow. Certainly the conceptions of all three characters have their sentimental aspects — Harold’s alcoholism, for instance, is never allowed to interfere with his Rock of Gibraltar stature — but it is perhaps only in some of Modine’s psychodramatic excesses and in the aforementioned camera angles that Pakula has allowed these simplifications to take over.

Otherwise, the characters are kept alive and unpredictable through the careful counterbalancing of their separate acting styles. Albert Finney, American accent and all, gives a model demonstration of how to hold the screen with a minimum of fuss — a method of suggesting reserves of untapped energy that must be a lot harder to pull off than he makes it seem. (The fact that Harold is associated with Houdini is hardly accidental — it compounds the play’s use of offstage space by implying that Harold is himself an iceberg, most of whose resources are invisible to the naked eye.) Matthew Modine, by contrast, is an anthology of visible tics and staccato gestures — not at all like the alternately serene and smoldering Joker he played in Full Metal Jacket, but something more nearly like a Brando-derived character in a Scorsese movie, a live wire whose perpetual rage makes even his casual movements potential acts of violence. While Finney glides and Modine stabs and sputters, Kevin Anderson acrobatically flops, rambles, and swings like a monkey through the clutter of the house, halfway between the eccentric grace of the former and the nervous indecision of the latter; where Finney is mainly straight lines and Modine is tortured angles, Anderson is basically curves.

In one of the strongest set pieces — a play within a play staged by Harold to test Treat’s ability to hold back his anger, with Phillip enlisted as a provocateur — all three styles are whipped together into a furious psychodrama that restages the emotional dynamics of the trio in an almost dreamlike form. Like the multiplication of two negatives, this fusion of unrealities, a dream within a dream, creates a sense of truth at loggerheads with all the ordinary scenes taking place outside the house.

The odd thing about such set pieces is that, for all their primitive and primal, nonintellectual content, they restage some of the same fascinating contradictions that can be found in such films as Jean Cocteau’s Les parents terribles (1948) and Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge (1963). About the former, critic and theorist André Bazin once wrote that because Cocteau’s play was markedly realist, “Cocteau the filmmaker understood that he must add nothing to the setting, that the role of the cinema was not to multiply but to intensify . . . if the room of the play became an apartment in the film, thanks to the screen and to the camera it would feel even more cramped than the room on stage. What it was essential to bring out was a sense of people being shut in and living in close proximity. A single ray of sunlight, any other than electric light, would have destroyed that delicately balanced and inescapable coexistence.” In the more avant-garde An Actor’s Revenge–centering on an aging Kabuki actor in drag as he traipses through a fantasy environment where the stage and the world are often indistinguishable — Ichikawa offers a dazzling and definitive illustration of the principle that the most cinematic way of filming theater is to keep it as theatrical as possible.

It goes without saying that Pakula never approaches the purity of a Cocteau or an Ichikawa — either of whom, I’d wager, would have eaten ground glass before even conceiving of a scene like Phillip rolling around in the field in front of his house. What matters more, though, is that Pakula has allowed most of Orphans to retain its theatrical juices, regardless of the bizarre consequences, and thereby stumbles into the same fertile territory of Cocteau and Ichikawa that engages with many of the same contradictions. As an art film, Orphans may be only a halfhearted effort; but in terms of Hollywood it qualifies as a rare act of courage.