These two short articles were written for the catalogue of the fifth edition of the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in 2004. Both are about neglected filmmakers who are or were also longtime friends of mine–although neither, to the best of my knowledge, has ever seen any films by the other, and they met for the first time at the festival, where complete retrospectives of both filmmakers were being presented. (I first met Eduardo in Paris in 1973, shortly after he’d finished working as a screenwriter on Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau, and I first met Sara about ten years later in New York, shortly before I saw her first major film, You Are Not I, and decided to devote a chapter to her in my book Film: The Front Line 1983.) Her complete works apart from her 2017 Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat are now available in a wonderful two-disc package, which can be found here.

When I was asked to write these two pieces for the BAFICI catalogue, I opted to make them each exactly the same length (942 words) and to make them rhyme with one another in various other ways. (Note: the last three images in this post, which for me evoke certain aspects of some of the films by both filmmakers, are all paintings by Remedios Varos: Insomnio I [1947], La Despedida [1958], and Bordando el Manto Terrestre [1961.]) — J.R

Two Neglected Filmmakers:

Eduardo de Gregorio and Sara Driver (2004)

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Eduardo de Gregorio’s Dream Door

It must be a bummer to be an Argentinian writer and/or filmmaker and constantly get linked to Jorge Luis Borges. It must be especially hard if you’re Eduardo de Gregorio, whose first major screen credit is on an adaptation of “Theme of the Traitor and Hero” for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 feature The Spider’s Strategm.

I don’t mean to question the credentials of de Gregorio as a onetime student of Borges — just the appropriateness of a too-narrow understanding to impose on a singular body of work that owes as much to cinematic references as to literary ones, and one that indeed juxtaposes the two almost as freely as it juxtaposes different languages and historical periods (while including all the cultural baggage that comes with each of them). For if we agree with historian Eric Hobsbawm that the overall development from the 19th century to the 20th and then to the 21st is a gradual slide from civilization to barbarism, I believe we’ve arguably accepted not only an operating hypothesis of Argentinian culture in general and of Borges’ work in particular, both steeped in a particular kind of cultural nostalgia, but one of the most precious legacies of both. And considering how roomy the 19th century is, it’s obviously a resource that can be put to radically different uses.

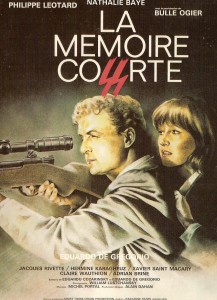

In the case of de Gregorio’s features and his participation as a writer in the elaboration of a few others, the literary tradition most in play is probably the Gothic — and especially one of the principal sites of that tradition, the Old Dark House, which crops up directly in The Spider’s Strategm (where it’s also known as Tara), Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974), Sérail (1976), Aspern (1984), Corps perdus (1989), and, more metaphorically, in my two favorites of de Gregorio’s own features, La mémoire courte (1979) and Tangos volés (2001). (In the heavy Langian menace of the former, it’s the tainted history of Nazism, functioning like an active form of decay inside a film noir in color; in the light, Renoiresque affection and swarming activity of the latter — appropriately overseen by a character named Octave, recalling Renoir’s own character in La règle du jeu — it’s the “old bright house” of a film studio.)

From another point of view, these houses in de Gregorio’s films function in much the same way as manuscripts, paintings, and films — as time machines that are also thresholds into alternate realities, which in Borgesian terms might be described as alternate fictions. For it’s important to recognize that what we call “reality” in de Gregorio’s universe is most often a matter of dialectical fictions: two scheming sexpots (Bulle Ogier and Marie France Pisier — whether they’re competing in Céline et Julie’s film-within-a-film or working in tandem in Sérail); the separate interests of art and commerce (in Sérail, Aspern, and Corps perdus); juxtapositions of the Anglo-American 19th century (via references to Collins, James, Poe, Stevenson, et al.) with the continental European or South American 20th — indeed, nearly always two or more separate national cultures interfacing and interacting across separate time frames and historical periods.

Basically a filmmaker of the fantastique — even when he’s rummaging around in a reasonable facsimile of real history in Aspern and an even more persuasive (if chilling) version of real history and politics in La mémoire courte — de Gregorio also participated in generating the other-worldly fantasies of Rivette’s Céline and Julie, Duelle, Noroît, and Merry-Go-Round (as well as the history of Jean-Louis Comolli’s 1975 La Cecilia), only the first of which is playing in this retrospective. All of these share with most of de Gregorio’s own features a universe where women, many of them divas, are often the ones in control. What they don’t share are the conniving and cynical men who try to deceive and outwit them — i.e., the heroes of Sérail, Aspern, and Corps perdus, played respectively by Corin Redgrave, Jean Sorel, and Tchéky Karyo. One thing that’s especially likable about Tangos volés — a film whose conscious influences include Hellzapoppin and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty — is the relative lack of malice in the male characters (played by, among others, Liberto Rabal, grandson of Francisco; Guy Marchand; Juan Echanove as Octave; and a little boy who irresistibly recalls Michael Chaplin in A King in New York) — although de Gregorio’s caustic wit is not entirely absent from his treatment of tangomania.

I’d like to conclude by citing a few other insufficiently recognized treasures in his work. There’s the only real performance as an actor (as opposed to cameo appearance) of Jacques Rivette, in La mémoire courte — which, combined with William Lubtchansky’s ravishing color cinematography and the paranoid intensity of the multinational script, makes this film, along with early Robert Kramer, one of the only true successors of Paris nous appartient (even if it gets cited as infrequently in Rivette’s filmographies as de Gregorio’s own performance in Straub-Huillet’s Othon gets cited in his). There are the interesting and varied ways of representing and evoking de Gregorio’s native Buenos Aires in absentia (in La mémoire courte, where it’s present only in documentary footage borrowed from coscreenwriter Edgardo Cozarinsky’s …; and in Tangos volés, where it’s entirely a matter of memory and pastiche) and perversely and dialectically shutting out most evidences of the city while actually filming there (in Corps perdus). There are three of Bulle Ogier’s most delicate and beautifully shaped performances, in Sérail, La mémoire courte, and Aspern. And finally, there’s the exhilaration as well as the heady vertigo of shuttling between eras and continents via what Tangos volés calls “la porte des songes” — a handy device for a nostalgic expatriate.

***

Sara Driver’s Dream Dog

It must be a bummer to be a woman surrealist — a tradition that is rarely acknowledged to exist, at least among American and European writers and filmmakers. In Mexican painting, there’s Frida Kahlo and Remedios Varo. But when it comes to fiction writers like Shirley Jackson or Flannery O’Connor, other affiliations such as “gothic” or “southern” always take precedence, much as “feminist” does when it comes to Jane Campion, Chantal Akerman, or Leslie Thornton. Possibly all of this is due to the abiding sexism of André Breton, Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dali, and other talented, macho Latin ideologues, but it seems in any case that David Lynch and Raul Ruiz are automatically deemed honorary members of the club while Sara Driver is usually deprived of any tradition at all, except maybe “weird” and “independent”.

I have to admit, though, that she makes things difficult — and difficult in the best sense — by being so contrary, even when it comes to only three extended narrative films to date. While we can readily speak about the surrealist “worlds” of a Buñuel, a Lynch, or even an Akerman (at least if we think of Belgian surrealism), the three films of Driver, even if we can easily call them all surrealist as well as “Driveresque,” clearly take place in three distinctly different worlds. That doesn’t mean that there aren’t various stylistic, thematic, and temperamental connections between them going well beyond the recurrence of various collaborators. Think of the dense and hyperactive soundtracks of all three, the downscale milieus, the trancelike rhythms, the layered relation of distant past to present (bringing to mind the fact that Driver spent her junior year in college abroad, studying archeology in Athens), the depictions of bullying power-mongers and solitary children, the dreamy passivity of seemingly hapless protagonists and the prominent attention given to their dreams, and chaotic eruptions of various kinds occurring in the midst of their compulsive routines, leading to the major plot developments in all three cases.

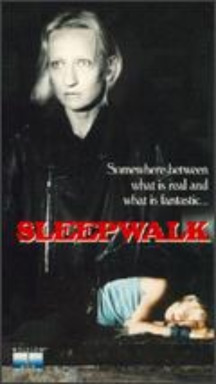

Perhaps an even more singular common trait in You Are Not I (1982), Sleepwalk (1986), and When Pigs Fly (1993) is the simultaneous urge to follow characters conceived in unabashed fantasy terms — a schizophrenic (Suzanne Fletcher) who can think herself into the social identity of her sane sister (Melody Schneider), a Caucasian mother with a Chinese son (Dexter Lee), two ghosts (Marianne Faithful and Rachel Bella) who move around with a rocking chair and its owners (Maggie O’Neill and Alfred Molina) — while charting their various interrelations with the world and each other with a great deal of plausibility. Put another way, she knows how to get the poetic and the prosaic, the supernatural and the mundane, to rub shoulders with one another. (Two perfect performances — Fletcher’s poetic fixity in You Are Not I, Molina’s mundane nonchalance in When Pigs Fly — form the center of each film.)

Still, the differences between Driver’s three films are huge, each one confounding many of the expectations set up by its predecessor. (The same is true of her 1994 short video documentary The Bowery — a fond, factual tribute to her own Manhattan neighborhood, narrated by local historian Luc Sante, that also manages to encompass a morbid, surrealist “Oddatorium” and references to “ghosts,” “a magic place,” and a “wonderland”.) Even though it begins like the way that Psycho ends, and is never entirely removed from mainstream horror, You Are Not I — an adaptation of a Paul Bowles story, made for a masters thesis in film school, that is surprisingly faithful (aside from the fact that a highway accident replaces a train wreck) — registers unapologetically like an art film, and so, in a very different way, does Sleepwalk (this time working closer to Jacques Rivette than to a Georges Franju, integrating choreography rather than literary narration into the mise en scène). Yet When Pigs Fly is informed at every turn by the character types of popular commercial cinema, Hollywood romantic comedy in particular; even the principal avowed influence is Topper.

Another significant distinction: the fantasy elements in You Are Not I can ultimately be traced back to the American tradition of Poe which associates them with mental derangement, and the fantasy elements in When Pigs Fly can apparently be related to Irish folk tales as well as the generic staples of Topper. But even though Sleepwalk is set in its entirety in the neighborhood of lower Manhattan where Driver lives, the film belongs more to the free-wheeling trappings of what the French call “fantastique” — which includes surrealism without being limited to it — than to any particular national or ethnic tradition. Could this be because the Bowery is itself a cultural melting pot, like much of New York? Significantly, the Chinese text being translated by the heroine derives from four separate fairy tales: one Chinese, one African, one by the Brothers Grimm, and one made up by Driver herself.

There’s also a shift from unbridled ferocity in the Bowles adaptation to a kind of fairy-tale malice (such as the loss of fingers and hair) on the edges of the much gentler Sleepwalk to a juxtaposition of wife-beating and murder with slapstick in the still gentler When Pigs Fly. Meanwhile, the same irreverence that can virtually start the latter film off with a dog’s giddy musical dream to match his master’s, and can later use a performance of Thelonious Monk’s “Misterioso” as a pretext for a lyrical theme park ride (and Marianne Faithful as a pretext for a lovely rendition of “Danny Boy”), can also, in the earlier Sleepwalk, use the Chinese Year of the Dog as a good excuse for making a passing executive bark in the street.