From the Chicago Reader (June 10, 2005). — J.R.

It seems like hardly anyone in the U.S. ever saw Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle, despite its enormous success elsewhere, apparently not so much because kids had trouble with it as because of the adult suits handling it. But Roger Ebert gave this film only two and a half stars while assigning Mr. and Mrs. Smith three stars the same week (June 10, 2005), suggesting that one of us was probably wrong — or maybe just that Japanese kids and I are both helplessly out of touch with the American mainstream as defined by some grown-ups. — J.R.

Howl’s Moving Castle

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and Written by Hayao Miyazaki

With the voices of Jean Simmons, Christian Bale, Lauren Bacall, Blythe Danner, Emily Mortimer, Josh Hutcherson, and Billy Crystal

The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Robert Rodriguez

Written by Rodriguez and Racer Rodriguez

With Cayden Boyd, Taylor Dooley, Taylor Lautner, George Lopez, Jacob Davich, David Arquette, and Kristin Davis

Mr. and Mrs. Smith

no stars (Worthless)

Directed by Doug Liman

Written by Simon Kinberg

With Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Vince Vaughn, Adam Brody, Kerry Washington, and Keith David

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Sometimes movies earmarked for kids are a lot more nuanced, sophisticated, and mature than the ones that are allegedly for grown-ups. As a nonparent, I often avoid PG fare, but Howl’s Moving Castle and The Adventures of Sharkboy & Lavagirl in 3-D suggest that maybe I shouldn’t. Conversely, during the two long hours of Mr. and Mrs. Smith, a deeply stupid and offensive action comedy-romance, I kept feeling I was being addressed as an obnoxious, heartless, and nihilistic grade-school brat.

Admittedly, Angelina Jolie in a dominatrix outfit breaking the neck of a wealthy client isn’t preteen fare, which is presumably why Mr. and Mrs. Smith is rated PG-13. But you have to be jaded to imagine anyone over 12 enjoying this. The studio must have reasoned that Jolie and Brad Pitt are movie stars, so anything they do would be seen as fun and attractive–-and what could be more fun and attractive than their trying to kill each other and just about everybody else in the movie? According to Simon Kinberg’s infantile script–-originally written as an MFA thesis at Columbia University (I kid you not) and not in any way a remake of the 1941 Alfred Hitchcock comedy with the same title–-the two have been married for five or six years, each unaware that the other is working secretly as an assassin for a rival organization until they’re assigned to bump each other off.

Maybe Kinberg and director Doug Liman were trying to be satiric, but the results are strictly generic. The only major character besides the Smiths is Pitt’s wimpy boss (Vince Vaughn), and no matter how many thoughtless murders the Smiths commit or how many lies they tell we’re supposed to slobber over them as if they were deities. By contrast, every character in Howl’s Moving Castle–-derived from an English novel by Diana Wynne Jones–is both lovable and seriously flawed, and though a war does rage around them, the only villains are the faceless forces on both sides that keep it going.

There are heroes as well as villains in Robert Rodriguez’s Sharkboy & Lavagirl, written with his son Racer, but the movie is mainly about a boy named Max (Cayden Boyd) whose overactive imagination gets him in trouble. The title characters and the 3-D sections, set mainly on the planet Drool, are products of Max’s fantasies, though the characters are based on people at his home and school. As in The Wizard of Oz and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T., we encounter both the twisted dream characters and the original models.

Sharkboy & Lavagirl can be obvious, as when a defense of the imagination quickly becomes preachy. People who’ve seen Rodriguez’s Spy Kids movies may find the tacky, low-budget effects suggesting a kind of Kmart surrealism a bit worn, along with his nonviolent scenario; nothing’s scary, and everything’s so light it’s on the verge of evaporating. Yet I’m still charmed by Rodriguez’s low-tech, antistudio ideology, a mainstay of his best work since the 1993 El mariachi. The landscape and weather on Drool consist largely of literary conceits and puns writ large–-a Stream of Consciousness flowing through a land of milk and giant cookies, a Train of Thought that keeps jumping off its tracks, a brainstorm attack, a banana split boat. Underlying everything is an unabashedly Luddite vision in which electricity is the villain–in the form of Mr. Electricity (George Lopez), a transmogrified version of Max’s teacher Mr. Electricidad, hobbling around on mechanical legs.

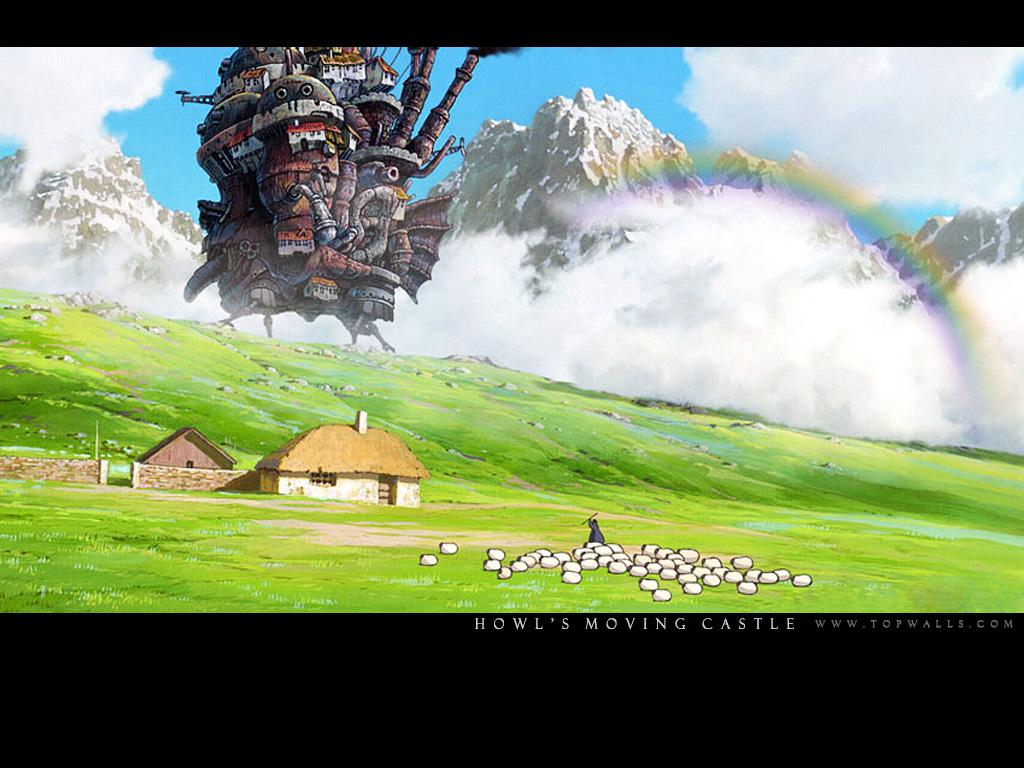

The castle in Howl’s Moving Castle is a weirdly animated amalgam of thing, creature, and place. So is much of the rest of Hayao Miyazaki’s wonderful movie–-whether it’s a flame named Calcifer (the voice of Billy Crystal), a scarecrow named Turnip, the endless stretch of steps leading to the royal palace, or a spectacular paradisiacal meadow. Everything and everyone is undergoing perpetual transformation in this enchanted universe, where magical spells serve either to clarify or to conceal certain traits but people, things, and places persist.

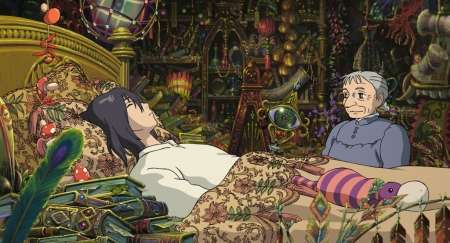

Most radically changed is Sophie, the heroine, who’s transformed by the obese Witch of the Waste (Lauren Bacall) from a withdrawn 18-year-old hatmaker (Emily Mortimer) into Grandma Sophie (Jean Simmons), the castle’s take-charge housekeeper. Grandma Sophie’s romantic feelings for Howl (Christian Bale), the young wizard and master of the moving castle, periodically make her look 18 again–to us and to herself, if not to the other characters. The greedy Witch of the Waste, who’s made herself young, is returned to senile old age as a punishment, but then she’s unexpectedly adopted and even indulged by the household of the moving castle. Howl, a sloppy if handsome cartoon prince, goes from being a brash warrior to an angry pacifist while periodically sprouting wings and undergoing other physical transformations.

Miyazaki, now in his mid-60s, has a refreshing and persuasive way of relating youth to old age and callowness to wisdom. Rather than presenting them succeeding each other and fighting for supremacy, he shows them coexisting peacefully. And he does this with characters so nuanced and real one keeps discovering new things about them at every turn.

A recent daylong reunion of my grammar-school class gave me back a few flashes of myself as a child. Howl’s Moving Castle did the same thing, bringing back images from dreams I’d long forgotten–dreams of distant lands and immense aerial vistas. I can’t swear these were dreams I had as a kid, but it’s irrelevant, because in some way we’re always children when we dream. And as adults we’re always rediscovering and revising our childhood–-which is related to why Grandma Sophie keeps recovering her 18-year-old self and then teaching that self a thing or two.

According to Richard James Havis in The Hollywood Reporter, Howl’s Moving Castle has already made $192 million in Japan, yet its success in the U.S. is uncertain. “Plotting is so multifaceted that it will confuse children,” he writes, “and it lacks the clear-cut heroes and villains typical of animation.” Does this mean he thinks Japanese children are more sophisticated and less easily confused than American children? Or that the $192 million paid for just Japanese grown-ups?

I’m less concerned about kids anywhere finding joy in this movie than I am about American adults who worry about the absence of clear-cut heroes and villains. Especially if they think the ones like those in Mr. and Mr. Smith are preferable–-as so many Hollywood honchos apparently do. Those honchos often claim to be taking their cues from American audiences, but I suspect more and more that this is a ruse. I suspect they make movies like Mr. and Mrs. Smith because, whether they realize it or not, they hate us and want to see their worst assumptions about us confirmed. The uncommon respect shown both kids and adults in Howl’s Moving Castle–-and its distaste for violence and war–-is an ideal rebuttal.

Published on 10 June 2005 in Chicago Reader, by jrosenbaum