This originally appeared in the January 10, 2001 issue of the Chicago Reader. It seems worth reprinting as a kind of adjunct to my overview piece about Oshima, written for Artforum in 2008 and also available on this site. –J.R.

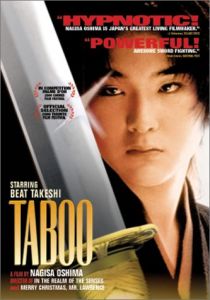

Taboo

****

Directed and written by Nagisa Oshima

With Beat Takeshi (Takeshi Kitano), Ryuhei Matsuda, Shinji Takeda, Tadanobu Asano, and Yoichi Sai.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Mark your calendars. Over the next six weeks, the Music Box is offering three eye-popping masterpieces from Asia. This is a welcome sign–-as is the popularity of the breezy Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon in the multiplexes–-that American theaters and audiences are finally recognizing that a lot of the best movies come from the other side of the planet and that there’s as much diversity among them as there is among ours.

Yi Yi, which opens March 2, is a three-hour feature set in contemporary Taiwan. It was just voted best picture of the year by the National Society of Film Critics, the first foreign-language picture to receive this honor since Akira Kurosawa’s Ran 15 years ago. Its writer-director, Edward Yang, is one of the two or three undisputed masters of Taiwanese cinema, and the Film Center gave us a full retrospective of his work in 1997. But Yi Yi is the first of his features ever to receive American distribution.

Chunhyang, which opens February 2, is a passionate love story set in the 18th century–-a stirring bit of storytelling and an operatic musical of sorts, at once modernist and traditional. It has the most vivid colors I can recall seeing since Hollywood sold off much of its Technicolor equipment to Korea, and it’s directed by the most respected old master in Korean cinema, Im Kwon-taek, who’s made close to 100 films since 1962. (His Fly High Run Far took fifth place on my 1995 ten-best list.)

The third masterpiece, opening this week, is Taboo, the most mysterious and least readily classifiable of the trio. It’s another period film, set in 1865, and it’s written and directed by the man many critics would call the greatest living Japanese filmmaker, Nagisa Oshima. Now 69, he made In the Realm of the Senses and Empire of Passion in the mid-70s and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence in 1982. Since then he’s released only one feature besides Taboo, the 1986 Max Mon Amour, filmed in France; it’s not one of his best films, and it’s barely known in this country. But then it’s difficult to find even his best work here; I’ve seen only about half of his 22 theatrical features (mainly the later ones), only one of his 22 TV documentaries, and none of his three TV dramas or three short films.

I’m honoring the request of New Yorker Films to refer to Taboo by its English title, but according to a Japanese friend, “taboo” isn’t an accurate translation of its original title, Gohatto-–a somewhat old-fashioned term that means “against the law” or “against the laws.” (One fascinating aspect of the Japanese language from a Western perspective is its lack of distinction between singular and plural nouns, which injects ambiguity into many titles.) Still, Taboo seems an appropriate title, given that throughout his career Oshima has been known, inside as well as outside Japan, as a taboo breaker.

I spent a couple of weeks in Japan in December 1999 as a guest of the Japan Foundation, whose foreign visitors’ program generously allows guests to decide where they go and whom they see. Oshima was the only person I mentioned who couldn’t meet with me, because his schedule was too busy. In spite of his reputation as a radical iconoclast, he’s perhaps best known in Japan as a TV talk-show host and guest. I saw him once on TV during my visit, and my guide’s translation of some of his remarks made him seem like a rough equivalent of Oprah Winfrey. When I later asked leftist film critic Tadao Sato if being on TV had forced Oshima to compromise his politics, he replied that, on the contrary, it had enabled him to express his political positions to a wider audience.

At the time of my visit, Taboo had already been screened for the press, though it hadn’t opened; throughout my trip it received favorable comments from practically all of the Japanese critics I met. Oshima had suffered a minor stroke in the mid-1990s when he was on a speaking tour in the United Kingdom, leaving the right side of his body paralyzed and delaying the start of shooting (he directed from a wheelchair). The filming was all done in Kyoto, using a few temples for some of the exteriors and the Shochiku studio that specializes in period films for everything else. I visited the studio–-the same one where Kenji Mizoguchi filmed The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums in 1939–-and spoke to the production designer for Taboo, Yoshinobu Nishioka, a modest and charming old master who’s worked on everything from Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu to Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge and self-deprecatingly described his work on the latter as “a bit much.” But he seemed justifiably proud of his work on Taboo.

Shochiku was the studio where Oshima started his film career in the mid-50s, before breaking violently with it in 1961 to become an independent, and the producer of Taboo is the son of a studio official from the time when Oshima worked there–-so the mythic resonance of Oshima returning to his origins wasn’t lost on anyone who’d followed his career. Yet Taboo is anything but a characteristic Oshima movie. (A Kyoto film academic who’d followed the shooting told me that Oshima’s direction focused on the placement and moves of the camera rather than on the actors, many of whom, like Takeshi Kitano, are among the most popular in Japan and were accorded a fair amount of autonomy.) The simple fact that it’s a period film distinguishes it from most of Oshima’s work, though both In the Realm of the Senses and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (arguably his last two major films) are also period films, albeit set in the 20th century. Taboo is also like the former film in that it links eros with death, and it’s like the latter in that it explores homosexuality within a military context. A more important quality distinguishes this film from many of his others: one doesn’t ordinarily associate his work with poetry and style, yet Taboo is above all a triumph of poetic style.

Adapted by Oshima from two sections of a historical novel (or two stories in a collection–-accounts differ) by a popular writer, Ryotaro Shiba, who died five years ago, Taboo is a haunting and dreamlike tale centered on a beautiful, androgynous, and narcissistic 18-year-old merchant’s son named Sozaburo Kano (newcomer Ryuhei Matsuda) recruited to become a samurai warrior in the Shinsengumi militia, a nationalist legion assigned to protect the shogun. At the Nishi-Honganji temple, Kano and another recruit–-Hyozo Tashiro (Tadanobu Asano), a low-level samurai from the Kurume clan–-are selected on the same day by Commander Isami Kondo (Yoichi Sai, best known as a film director) and lieutenant Toshizo Hijikata (Beat Takeshi, better known in the U.S. as writer-director-actor Takeshi Kitano, who also played in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence). Almost immediately, everyone shows an unusual, even obsessive interest in Kano. Tashiro tries more than once to seduce him and is rebuffed each time, though Kano admits at one point that he’s “never known a woman’s caress” and he later avoids sleeping with a prostitute when an officer tries to persuade him to. Tashiro also gets five days of detention as punishment after he sneaks off to watch Kano effortlessly behead a prisoner (”That’s how they test newcomers,” says Tashiro).

Rumors circulate about Kano and other men in the Shinsengumi, and whether this feverish speculation is the result of repressed homoeroticism or simple curiosity or some combination thereof is never made clear. Kano, who’s generally dressed in white (the color of mourning in Japan), seems to figure increasingly as an angel-of-death figure, though whether this is willed or inadvertent is also never made clear. We can’t even be sure that Tashiro is genuinely smitten with him––perhaps his sexual pursuit of Kano is a form of competition, an indication of his desire to be the one in power. Sometimes these ambiguities are discussed by the officers, sometimes they’re part of internal monologues delivered offscreen, and sometimes they’re expressed in the offscreen narration or in the extended silent intertitles that appear between certain sequences. Like the singing narrator of Chunhyang, who’s sometimes heard offscreen and sometimes seen performing in front of a live contemporary audience, these fascinating intertitles––often appearing in bunches and concentrating on codes and prohibitions relating to military conduct––are simultaneously traditional and avant-garde, harking back to silent cinema while adding yet another highly modernist form of ambiguity.

As Chuck Stephens points out in an informative article in Film Comment, most of the officers in the story, unlike Kano and Tashiro, are based on real people. Having film directors play the two most prominent ones only adds to the multilayered ambiguities––including the relation of all these uncertainties to Oshima himself, who’s heterosexual. (His problematic linking of sex and violence, often through rape, in his other films––examined by Maureen Turim in her valuable recent book about Oshima––is by no means restricted to gay characters.) “Contrary to popular opinion,” Stephens argues, “Gohatto isn’t really about Kano, or forbidden and perhaps fatal sexuality, or the passion of men for men. Gohatto––like Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence––is about the looks on Takeshi Kitano’s face.” I agree that the film is about those looks, but it’s also about the states of mind suggested by the decor, starting with the realistic use of temple exteriors and gradually evolving into an expressionist exterior landscape with artificial fog and highly theatrical yellow lighting, where the differences between objectivity and subjectivity, reality and imaginative projection, outside and inside, become increasingly difficult and even impossible to sort out. Certainly Takeshi Kitano’s face––and, in the stunning final sequence, his movements as he cuts down the upper half of a blossoming cherry tree––plays a pertinent role in all this ambiguity, and it’s clearly part of the film’s mystery that it raises the question of whether his performance, in keeping with the evolving decor, is naturalistic or expressionistic.

I would speculate further that part of the ambiguity may relate to the above-mentioned lack of a clear distinction between singular and plural Japanese nouns, and how that may reflect a lack of a clear distinction between individuality and community in Japanese life and thought, at least in relation to Western models. Significantly, in Japanese culture eroticism is both a potential zone for individual rebellion and a potential zone for conformity. Yasuzo Masumura (1924-’86), a fascinating film critic and highly erotic studio director who attended film school in Italy and went on to direct 54 Japanese features––celebrated by Oshima before he began directing and permanently repudiated only three years later––spent much of his career railing against Japanese conformity and defending individuality, yet in his films it’s often impossible to separate individuality from madness. The uncertainty in Taboo about sexual orientation and sexual passion––how they relate to individuality and groupthink, liberation and free movement, confinement and discipline, macho and feminine traits, life and death, health and obsession––seems cut from the same cloth.

Far from being a cinephile, Oshima virtually rejected Japanese cinema as a whole for political reasons around the time that he became an independent filmmaker. Traces of his rejection are apparent in the sociological approach of his 1995 documentary 100 Years of Japanese Cinema: he accords one clip apiece to Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, and Akira Kurosawa (and one still to Masumura) and four clips to himself, and he discusses most of the remainder of his work and very little of theirs–making it scandalous that the British Film Institute gave him the job of “representing” Japanese film history.

In spite of this scorched-earth policy, one of the biggest surprises of Taboo is that much of it registers as a multifaceted tribute to Mizoguchi––in its long takes; in its lyrical and nearly constant camera movements (typically very slow and often following semicircular paths around two men conversing, as if to compound the ambiguity in how we view their shifting relations); in the voluptuously theatrical, Kabuki-like entrance of the prostitute, dressed in flaming red as she approaches the camera; in the ghostly and atmospheric studio expressionism, with the lines separating reality and fantasy becoming increasingly vague; and even in a direct allusion in the dialogue to the literary source of Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (here given the English title Tales of the Moonlight and Rain). A chamber piece abetted by one of Ryuichi Sakamoto’s loveliest scores as it gradually drifts from narrative into a labyrinthine reverie, Taboo distills a kind of troubled poetry that ultimately asks if beauty is tied to evil and if desire is connected to death. Yet far from imposing these and related hypotheses as if they were foregone conclusions, the film is content to ponder them from a careful distance, letting the cherry blossoms fall where they may.