Both of these very short pieces were written in 2002 for Understanding Film Genres, a textbook that for some unexplained reason was never published. Steven Schneider commissioned them. — J.R.

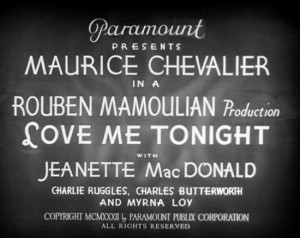

Love Me Tonight

There are two distinct aesthetics for movie musicals, regardless of whether they happen to be Hollywood or Bollywood, from the 1930s or the 1950s, in black and white or in color. According to one aesthetic– exemplified by Al Jolson (as in The Jazz Singer) or the team of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers (as in The Gay Divorcee or Top Hat–a musical is a showcase for talented singers and/or dancers showing what they can do with a particular song or a number. According to the second aesthetic, exemplified by Guys and Dolls —- the two leads of which, Marlon Brando and Jean Simmons, aren’t professional singers or dancers — the musical is a form for showing the world in a particular kind of harmony and grace and for depicting what might be called metaphysical states of being. The leads are still expected to sing in tune, of course, but notions of expertise and virtuosity in relation to their musical performances are no longer the same.

Most musicals, of course, partake of both aesthetics. Singin’ in the Rain features the superb dancing of Gene Kelly, but his title number also shows him in a kind of graceful harmony with the weather — projecting a particular kind of exuberance that relates to an entire city street as well as his own body and the elements. Jean Hagen is ridiculed as a strident “amateur” when it comes to her voice as an actress in talkies—though paradoxically and ironically, the real Jean Hagen dubbed the sweet singing voice assigned to the heroine, Debbie Reynolds, reversing the movie’s fictional premise that Reynolds was dubbing Hagen.

One might argue that musicals which record live and undubbed singing and its accompaniment—-as the earliest talkie musicals did—–are conceived as containers for particular performances, whereas musicals that work with prerecorded songs come closer to metaphysical statements. A superb early example of the latter is Love Me Tonight (1930), which recorded its entire Rogers and Hart score before shooting started—–a score featuring a French pop singer (Maurice Chevalier) and an operatically trained American singer (Jeanette MacDonald) who had already costarred in three stylish musicals made by Ernst Lubitsch at Paramount (The Love Parade, Monte Carlo, and One Hour With You), as well as many other singers as unskilled as Brando or Simmons, such as C. Aubrey Smith, Charles Ruggles, and Charles Butterworth.

Love Me Tonight was directed by Rouben Mamoulian, a Russian-born Armenian who became famous in 1927 for directing Porgy on the New York stage—along with Porgy and Bess, the Gershwin opera-musical derived from it, eight years later. Between Porgy and Porgy and Bess, he directed Love Me Tonight, which begins with an adaptation of the “Symphony of Noises” that he created on Catfish Row at the start of Porgy, transposed to Paris waking in the early morning—–a metaphysical statement if there ever was one, with every move of a sweeping broom, workman’s drill, and carpet beating in a city neighborhood cleverly orchestrated into a musical whole. Carrying this principle much further, the movie offers rhyming couplets in its dialogue (as did another superbly stylized Rogers and Hart musical with Al Jolson three years later, Halleluah, I’m a Bum), as well as an early song, “Isn’t It Romantic?”, that travels like wildfire across a whole country—–from a tailor (Chevalier) in his shop to his customer to a cab driver to the driver’s fare (who happens to be a songwriter), from the songwriter riding on a train to a troop of marching soldiers in the countryside to a band of Gypsies—–finally reaching a fairy-tale princess (MacDonald) on the balcony of her chateau. As critic Tom Milne once pointed out, the whole film transpires like “one long, unbroken production number.” And equitably moving all the way from a working stiff to royalty—–before the plot brings Chevalier to the same chateau, to get paid for bills run up by the Vicomte de Vareze (Ruggles), the Princess’s brother—–anticipates the subsequent romance between the leads in musical terms. Impersonating a nobleman, Chevalier successfully courts the Princess until his imposture and real profession is revealed.

The advantage of including nonprofessional singers in the relay of “Isn’t it Romantic?” is to prove that anyone can become part of the musical universe—–a sense of sharing basic to many Depression musicals that made everyone in the audience feel included. Later on, the same kind of democratic mixture of singers is effected in two other pivotal songs, “Mimi” and “The Son of a Gun is Nothing But a Tailor,” as they freely pass through the castle’s household, gaining many different kinds of comical and musical inflections from nobility and servants alike. Indeed, as the latter song’s title suggests, some version of class warfare is being waged inside this playful musical, which pits working-class pop culture (Chevalier) against aristocratic “high” culture (MacDonald) inside a operetta-fantasy version of contemporary Europe as dreamt by America. During an era in which class barriers were every bit as unbridgeable for most people as they are today, the notion of a magical form of class mobility in which music and love ultimately counted for more than money was irresistible to an audience that couldn’t afford luxuries. (Significantly, Paramount’s press book for Love Me Tonight called Chevalier “The Aristocrat of the People”. And as musical scholar Rick Altman has pointed out, the Princess and her chateau is identified with the past, the tailor and Paris with the present.)

Making fun of itself throughout, Love Me Tonight revels in the sort of absurdities that such a fantasy entails, especially at the film’s climax. Leaving the chateau in disgrace as a son-of-a-gun tailor. Chevalier takes the train back towards Paris, until the Princess, assuming the usual male role, gallops desperately ahead of him, and stops the train dead in its tracks.

Suggested Reading: Mamoulian by Tom Milne, Bloomington and London: IndianaUniversity Press, 1969; The American Film Musical by Rick Altman, Bloomington and Indianapolis: IndianaUniversity Press, 1987.

Postscript (October 21, 2008): Chris Schneider (apparently no relation to Steven Schneider) has emailed me the following:

“I loved your piece about Love Me Tonight, the one that was recently posted in your site.

There’s is one small error, though, which should be cleaned up on the next occasion that you use the Mamoulian portion of the article.

You mention how Jean Hagen’s voice was used for Debbie Reynolds. Yes, but … it was only the *speaking* portion of that scene that used Hagen (the “our love will last till the stars turn cold” stuff). The singing employed the voice of one Betty Noyes.

Here’s a link to a page about movie dubbers put together by someone I trust:

http://www.barbaralea.com/Dubbers/dubberslist.html

IMDb lists Noyes, too.

Doesn’t prevent me from admiring the overall piece you had written, however.”

*****

Mulholland Drive

Starting with Blue Velvet, David Lynch has often gravitated (in Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks, Lost Highway, and Mulholland Drive) towards neonoir—–a visual style which, like noir itself, can’t be called a genre because, in spite of contemporary settings, “it looks backward to an imaginary past,” as James Naremore has put it, imposing our own agenda on the 1940s and 1950s. The original noirs weren’t called that in the U.S. when they were new; this was a French term for those crime thrillers that only started gaining currency in the U.S. during the 1970s. And calling films that imitate them neonoirs imposes our own view of their models over the way they were understood in their own times.

What makes Mulholland Drive–originally conceived as a TV pilot and rejected as such, then expanded after some French producers stepped in—especially satisfying as neonoir is its take on a subject, contemporary Hollywood, that Lynch knows something about. His affection, moreover, for his two heroines gives these characters a density that is rare in his films. Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), an aspiring actress from the sticks, and Rita (Laura Elena Harring), the amnesia victim she takes on as friend and lover, are both blank slates and unspoiled hopefuls in the narrative who eventually prove to have dark, corrupted twin selves showing the potentially ruinous effects of FunCity. What neonoir styling does for these four characters is root them in a city nostalgically fixated on its own past.

Suggested reading

Hoberman, J. and Jonathan Rosenbaum, Midnight Movies, 2nd edition, New York: Da Capo Press, 1991, pp. 214-251 & 322-324 (on Lynch’s early career).

Naremore, James, More Than Night: Film Noir in its Contexts, Berkeley/Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998, pp. 273-275 (on Lost Highway).

Nochimson, Martha P., “New York Film Festival 2001,” Film-Philosophy, Vol. 5, no. 30, October 2001 (on Mulholland Drive).