From the Chicago Reader (June 14, 1996). — J.R.

Films by Abbas Kiarostami

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

This month is an unusually rich one at the Film Center, especially for work that’s generally unavailable. Every Thursday there’s a classic film noir, with the rarely screened ultraminimalist Murder by Contract (1958) a particular highlight. Every Friday and Tuesday there are features by the late mannerist maestro Jean-Pierre Melville — an innovative director of French art movies (The Silence of the Sea, Les enfants terribles) who eventually became a specialist in American-style gangster films (Le doulos, Second Breath, Le samourai) and a homoerotic cult favorite of Quentin Tarantino and John Woo. (Catch Melville’s 1965 Second Breath this Friday and marvel at the bizarre sensibility and consummate craft that combine to lovingly duplicate the texture of a cheesy, nondescript Columbia Pictures noir of the 50s.) And best of all is a program devoted to Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami, including his four major features, over the next two weekends.

Both the Melville and the Kiarostami retrospectives are close to being complete. The missing Melville titles are 24 Hours in the Life of a Clown (his only short film, 1946), When You’ll Read This Letter (1953), and The Elder Ferchaux (1962), but no less than 11 features are showing this month. Omitted from the Kiarostami retrospective are three features — The Experience (1973), The Wedding Suit (1976), and The Report (1977) — and around half a dozen shorter works from the 70s, some of which are said to be lost, but seven features and nine shorts are included. (I especially regret the absence of The Report — a highly uncharacteristic melodrama about marital discord that I haven’t yet managed to catch up with.)

Five of the Kiarostami features have shown at the Film Center before, but everything else is a Chicago premiere. In many respects the short films — many of which I first saw last August at the Locarno film festival — are the real revelations in the series. Most of these works are conceptual and experimental pieces having something to do with children, and many of them have a fascinating relationship to Lehrstücke, or “learning-play,” a form closely identified with Bertolt Brecht. This isn’t to suggest that they’re political in the sense that Brecht’s learning-plays are, that they critique either the state of Iran or the state of Islam; but they often critique the state of cinema — that is, cinema as a partially self-contained system of beliefs, practices, and power relations. In this respect, a statement by Kiarostami recently cited by critic Godfrey Cheshire seems pertinent: “We can never get close to the truth except through lying.” Clarifying how and why the cinema lies is a central part of his enterprise.

As Brecht wrote in 1936, in an essay on pre-Hitler German drama, the learning-play “holds that the audience is a collection of individuals, capable of thinking and of reasoning, of making judgments even in the theater; it holds [this audience] as individuals of mental and emotional maturity, and believes it wishes to be so regarded.

“With the learning-play, then, the stage begins to be didactic….The theater becomes a place for philosophers, and for such philosophers as not only wish to explain the world but wish to change it.”

The main Kiarostami films I have in mind are Two Solutions for One Problem (playing June 22 and 23 with Life and Nothing More…, also known as And Life Goes On…) and So Can I (both 1975), Toothache (1980), Regularly or Irregularly? (1981), The Chorus (1982), and Fellow Citizen (1982). These films — unlike such charming documentary-style narratives as Bread and Alley (1970), Recess (1972, playing June 15 and 16 with Homework), and Solution (1978, playing June 15 and 16 with Close-Up) — are didactic and philosophical, whether they take the form of lessons or investigations.

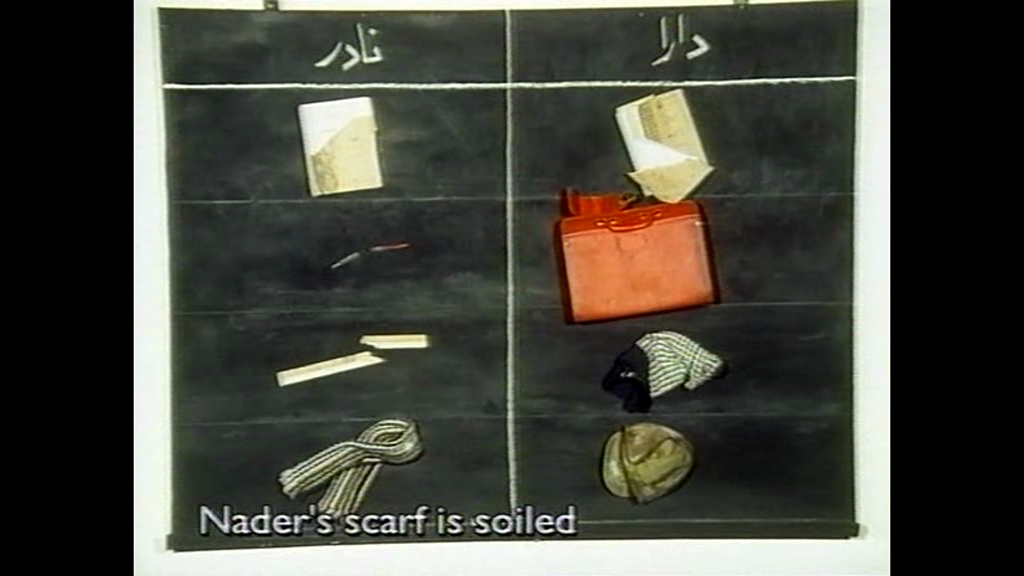

In Two Solutions for One Problem, where, significantly, the opening credits are written on a blackboard, two little boys at school become the protagonists in an extended moral lesson. When Nadar returns Nara’s notebook with its cover torn, Nara has two options: one entails revenge (leading to escalating acts of violence), the other involves using glue (maintaining their friendship). The morality of this five-minute movie is simple, but the comedy and mise en scène are dazzling as each boy in perfect deadpan rips up something belonging to the other — a curious kind of demonstration combining the rigor of experimental filmmakers Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet with the surefire physicality and methodical serial progressions of Laurel and Hardy. And later, when the behavioral choices are magically codified on the blackboard in parallel columns that contain objects as well as words, the lesson is virtually translated into rebus form.

In So Can I a comparable dialectic is set up involving the movements of animals in clips from animated cartoons and the efforts of two little boys to ape the gestures. Here again the concept is ultrasimple, but the illustration entails the creation of an abstract space that contrives to combine a classroom, animated film footage, and other settings where the imitated gestures are played out. (Alas, the payoff shot in the final gag — a cut from a live-action airplane taking off to the confounded expression of a boy unable to duplicate that maneuver — was missing from the print shown at the Film Center two weeks ago.)

In The Chorus — a straight, lyrical narrative involving a grandfather who periodically takes off his hearing aid while going for a walk and after returning to his apartment — the lesson becomes a strictly acoustical demonstration of what a particular neighborhood of Tehran sounds like with and without such assistance. In Fellow Citizen — a pure documentary detailing the encounters of a traffic cop informing drivers that they can’t proceed in one direction — the maintenance of the same camera angle throughout gives a strict formal pattern to the investigation. Toothache — a simple piece of didacticism about dental hygiene — becomes both a narrative about the tooth care of three generations of males in the same family and a documentary exhibition of one little tyke with a toothache howling in pain throughout the demonstration.

In Regularly or Irregularly? [also known as Orderly or Disorderly], the most philosophically profound of the shorts, we get alternate documentary takes of kids arriving at a playground or boarding a bus and pedestrians crossing the street in patterns that are initially chaotic and then formally ordered, “irregular” and then “regular.” The roles played by the filmmakers in controlling these patterns remain ambiguous, but their hilarious offscreen critiques of the chaos make brilliantly clear how much everyday deception is involved in fashioning documentaries — in the preparatory work as well as in the cut-and-paste editing — a theme that’s elaborated on years later in Homework (1989) and Close-Up (1990).

The much more conventional 1985 First Graders — the only Kiarostami film I dislike, which showed at the Film Center last week — traffics in the same sort of deception criticized by the later films by refusing to acknowledge either the presence of the filmmakers or the power they enjoy in recording the responses of six-year-old boys sent to the principal’s office, in a school located in one of the poorest sections of Tehran. Evocative at times of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, First Graders places far too much emphasis on the paternal “wisdom” of the principal as he dispenses justice, which implicitly valorizes Kiarostami’s position.

This sort of tainted relationship between filmmaker and subject begins to be acknowledged and critiqued in Homework, in which Kiarostami films himself interviewing schoolboys about how they do their homework. In the very act of cutting to reverse-angle shots of himself and his cameraman — shots that obviously require the services of an additional cameraman, who isn’t acknowledged — Kiarostami begins to foreground some of the implicit contradictions of his own lying in his pursuit of documentary truth. But it’s only in Close-Up — one of two philosophical peaks of his oeuvre (the other is Life and Nothing More…) — that he begins to fully deconstruct the documentary form itself and the whole “state of cinema” in the process.

Putatively a documentary, Close-Up (showing this Saturday and Sunday) is in fact a multifaceted critique of the documentary form. The real-life incident that provoked it — surprisingly similar to the real incident that inspired John Guare’s play Six Degrees of Separation — was the impersonation of a famous Iranian film director, Mohsen Makhmalbaf (Kiarostami’s only real peer), by an impoverished, out-of-work printer named Hossein Sabzian. Introducing himself as Makhmalbaf to a wealthy middle-aged woman on a bus, Sabzian got himself invited to her home, where he persuaded the entire Ahankhah family (mother, father, and grown son) that he planned to make a film in their house, using them as nonprofessional actors. Once his ruse was discovered the police were alerted, and they turned up with a reporter from Soroush magazine and arrested him. During his trial, Sabzian freely admitted that he undertook this fraud largely to be treated with respect, and the Ahankhah family was eventually persuaded by the judge to drop charges. (In the Manhattan incident that inspired Six Degrees of Separation a black youth persuaded a wealthy white couple that he was the son of Sidney Poitier and that his father wanted to cast them in the movie version of Cats; this youth was also arrested, but, if memory serves, the couple didn’t drop charges, and the youth certainly didn’t play himself in the play or movie.)

Having read about the incident, Kiarostami decided to restage every significant part of the story using all the real people. In other words, beginning with one lie, Sabzian’s impersonation, Kiarostami proceeded to generate several other lies — or at best half-truths — by getting all of the people to impersonate themselves and thereby promulgate their own versions of what happened. Close-Up begins with the Soroush reporter and two policemen getting into a cab to go to the Ahankhah residence and make the arrest. En route, the reporter cheerfully compares himself to Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci, clearly hoping his scoop will make him internationally famous (which is exactly what happened). As a result, one’s sense of a “manufactured” news event is quickly established on several levels at once. The reporter, Sab-zian, and Kiarostami are playing three different versions of the same game, each capitalizing on the awe and intimidation ordinary people feel about movies; by the time the film is over, every participant — including the family, the judge, Makhmalbaf, and the audience — has agreed to become an active part of the boondoggle.

Subsequent scenes show Kiarostami meeting Sabzian in prison, the various procedures leading up to the trial, and then a restaging of the trial itself, with flashbacks showing various stages of the fraud until we arrive at a replay of the opening scene of the reporter and policemen arriving at the house, this time told from Sabzian’s point of view. At the trial, Kiarostami explains, he’s using two cameras — one with a zoom lens to record the court proceedings, the other focused on Sabzian in close-up, which allows him to address Kiarostami (and therefore the viewer watching Close-Up). Kiarostami and his film are offering Sabzian a second court of appeal, and the restaging of the events leading up to the arrest from Sabzian’s viewpoint allows us to rethink what’s happening on his terms. As in Françoise Romand’s Mix-Up, Kiarostami may be trying to improve everyone’s mental health by restaging the events — offering psychodrama as therapy to several deluded or self-deluded individuals, with Sabzian singled out as both the prime pathetic victim and the main beneficiary. (The fact that he chooses to impersonate a film director rather than an actor surely tells us something about the difference between Iranian society and ours –including the relative prestige of artists in Persian culture, an issue touched on in the trial itself.)

Finally Kiarostami generates a new chapter in the story by arranging a meeting between Sabzian and the real Makhmalbaf, who gives Sabzian a lift on his motorbike to the Ahankhah residence, stopping on the way so a tearful Sabzian can buy the family a bouquet of flowers — all of which is filmed in long shot. Playing further with the documentary form’s rhetoric of actuality, Kiarostami even fiddles with the sound track carrying the conversation between Makhmalbaf and Sabzian so that the sound periodically shuts off — an effect that’s fictionalized on the same sound track by references to faulty wiring in the microphone. Clearly our desire to accept this manufactured effect as real becomes another version of the predicament of the Ahankhahs — not to mention the predicament of Sab-zian, whose obsession with Makhmalbaf’s poetic depiction of suffering in The Cyclist (a genuine appreciation of his art) is what sets in motion all the other forms of deception.

These momentary suppressions of the sound track echo a more obviously deliberate and sarcastic/ironic effect at the end of Homework that involves the chanted prayers of schoolboys — perhaps the closest thing to a political critique in his entire oeuvre. Within Close-Up the bouquet of flowers “rhymes” with a bouquet picked by the cabdriver during Sabzian’s arrest in the opening sequence — a poetic interlude that also includes a spray can rolling across the street, another playful motif that recurs later. Indeed, such recurrences point to how thoroughly Close-Up, like virtually all documentaries, consists of shaped as well as “found” material, even when apparent accidents like the rolling spray can are involved.

Close-Up is the most intellectually dense and in many ways the most subtle of the features playing in this retrospective, but I would single out Life and Nothing More… as the most beautiful, mysterious, and moving. Its overarching theme — the relations between filmmakers and ordinary people — is the same as that of Close-Up and Through the Olive Trees, Kiarostami’s most recent feature. (A just-completed feature concerning suicide is expected to premiere at the Venice film festival late this summer). Yet the role played by landscape in Life and Nothing More… and Through the Olive Trees is much more pronounced, and in both films Kiarostami proves himself a master of the “cosmic” long shot who periodically imposes physical distance as a form of philosophical detachment and humor. (Whether or not he’s been influenced by Jacques Tati in this respect, Kiarostami has been swimming in the same waters for the past quarter of a century — something that’s detectable in his earliest shorts.) Having written at length in the Reader about Life and Nothing More… in 1992 and Through the Olive Trees last year, I’ll deal with them only in passing here. But they’re as important as anything that’s happened in movies in the 90s.

In Life and Nothing More…, a filmmaker — actually an actor (Farhad Kheradmand), clearly standing in for Kiarostami — is returning with his little boy to the remote mountain area of Kiarostami’s 1990 feature Where Is My Friend’s Home?, a few days after an earthquake killed more than 50,000 people in the region, hoping to learn the fate of two of his child actors. As in Close-Up, this is a restaging of something that really happened; Kiarostami’s car, the locations, and many of the people he and his son met remain the same. Kiarostami’s stand-in carries no camera and is accompanied by no crew, so in this respect the film, for all its documentary aspects, is a conventional fabrication and not a wholesale unpacking of the documentary form the way Close-Up is. But the implied social distance between the middle-class filmmaker and the working-class people he encounters remains a constant, and the same thing applies in Through the Olive Trees, which returns to the same mountain area to examine the relationship between Kiarostami (played this time by Mohamad Ali Keshavarz) and one of his nonprofessional actors (playing himself) during the shooting of Life and Nothing More... And Farhad Kheradmand is on hand again as the actor playing Kiarostami in the previous film — which suggests the degree to which Kiarostami’s fascination with the paradoxes of truth and artifice in filmmaking has continued to enrich his work.

It isn’t the least bit surprising that Kiarostami isn’t mentioned in the 50 Greatest Directors cover story in the April 19 issue of Entertainment Weekly. Characteristically weighted toward figures whose work is already widely available and has recently turned a profit, this magazine’s pantheon also excludes such directors as Michelangelo Antonioni, Tex Avery, Stan Brakhage, Robert Bresson, John Cassavetes, Charlie Chaplin, Alexander Dovzhenko, Carl Dreyer, Louis Feuillade, Robert Flaherty, Samuel Fuller, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Joris Ivens, Chris Marker, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Ousmane Sembène, Michael Snow, Erich von Stroheim, Andrei Tarkovsky, and King Vidor — in other words, most of the history of film as an art. Yet it somehow makes room for Woody Allen, Tim Burton, Francis Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Sidney Lumet, and Oliver Stone. Since Entertainment Weekly‘s agenda, like that of Premiere and the New York Times, is to ratify what’s already popular and to declare that the rest isn’t worth bothering with, it couldn’t possibly entertain putting an undistributed filmmaker on the list. (Through the Olive Trees technically has a distributor, Miramax, but it regularly dumps or hides many of its best releases; for instance, it bought the color restoration of Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête in 1994 but has yet to release it anywhere. Since it’s part of Miramax’s brief to pick up foreign films to prevent other distributors from carrying them, the spectator clearly matters least in such transactions.) Significantly, when one of the leading film critics in New York had the temerity to place Through the Olive Trees at the top of his ten-best list last year, he became the laughingstock of his editors — none of whom of course had seen Kiarostami’s film, but all of whom were apparently scandalized by the thought that an Iranian movie could be given such privileged treatment.

Outside the peculiar ideological constraints of this country’s mainstream Kiarostami’s importance to the history of world cinema seems a little less outrageous. “When Satyajit Ray died I was quite depressed,” Akira Kurosawa has said. “But after watching Kiarostami’s films, I thought God had found the right person to take his place.” Jean-Luc Godard ranks Kiarostami’s work much higher than Kieslowski’s, and in Paris a couple of weeks ago I turned on the TV in my hotel room and found a feature-length documentary about Kiarostami in progress. To get a taste of this giant in Chicago you’d better hightail it to the Film Center this weekend or next; don’t think you’ll be able to catch up with him later on video or cable, because the American mainstream has firmly established that he doesn’t exist.