This appeared in the May 14, 2004 issue of the Chicago Reader, and occasioned one of the few thank-you notes I’ve received from a filmmaker for a review. I hope both Guy Maddin and those reading this will forgive me for immodestly reproducing his email: “Dear Jonathan: I usually try to avoid setting precedents that violate what should be a no-fly zone between critics and filmmakers, but I must say that your review of Saddest Music left me feeling understood at last!!! What a feeling. Thank you for supplying this euphoria. You also win bonus points for the Laura Riding discovery — I always liked her characters’ names. George Toles, who is terrified of reading reviews, will be thrilled to see his unsung name given its proper due. Not only that, you disabled Anthony Lane’s stinkbombs. A million thanks, Jonathan!! Warmest, Guy” — J.R.

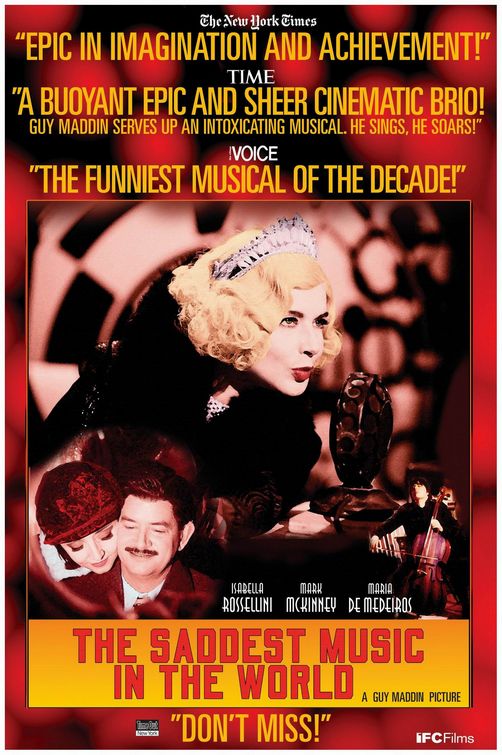

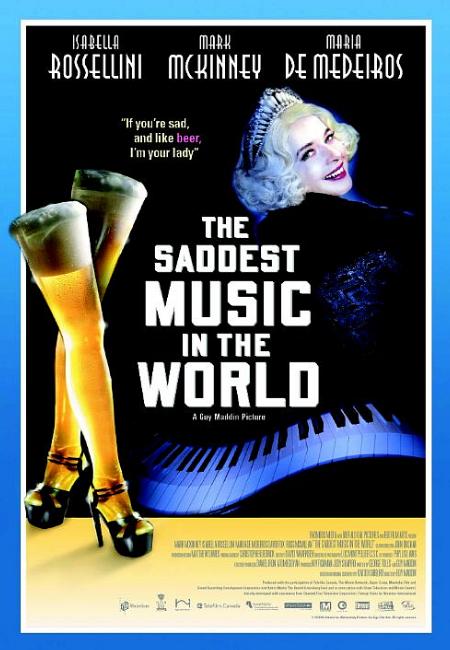

The Saddest Music in the World

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Guy Maddin

Written by George Toles, Maddin, and Kazuo Ishiguro

With Mark McKinney, Isabella Rossellini, Maria de Medeiros,

David Fox, and Ross McMillan.

To Guy Maddin, every contemporary story that feels true is at bottom an amnesia story. — screenwriter George Toles

When all the archetypes burst out shamelessly, we plumb Homeric profundity. Two clichés make us laugh but a hundred clichés move us because we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, celebrating a reunion. — Umberto Eco, “Casablanca: Cult Movies and Intertextual Collage”

Guy Maddin has reached a new expressive plateau with The Saddest Music in the World. It reprises the key elements of his previous work — the look and feel of scratchy late silents and early talkies (mainly black and white, with a few lush interludes in two-strip Technicolor) and themes involving Canada, amnesia and other forms of repression, war and wartime loss, oedipal conflict, mutilation, and unabated romantic despair — all touched with deadpan comedy and melodramatic excess. New to the mix are two glamorous international stars (Isabella Rossellini and Maria de Medeiros), some of the accoutrements of a Hollywood musical, a more clearly conceived and executed narrative, more apparent emotion, and a hilariously apt satirical allegory about Canada, the U.S., and the rest of the world.

As usual with Maddin, I can’t even begin to furnish a synopsis without sounding hyperbolic and slightly breathless. The film is set in 1933, at the height of the Depression, in Winnipeg, Maddin’s hometown. Beer baroness Lady Port-Huntly (Rossellini), whose name appears to have been suggested by Laura Riding’s great 30s story “Reality as Port Huntlady,” announces a contest to find the “saddest music in the world” as a way to promote her brew. Hoping the imminent end of prohibition in the U.S. will create a new demand for her beer and inspired by the London Times‘s selection of Winnipeg for three years in a row as the “world capital of sorrow,” the self-styled Beer Queen of the Prairie invites musicians from around the world to compete for the $25,000 prize, appointing herself the sole judge. She even has a slogan: “If you’re sad and like beer, I’m your lady.”

Two countries compete at each preliminary session: alternating musical snatches are interrupted by Port-Huntly, operating a loud buzzer that suggests a tacky TV-game-show device, and the winner gets to slide down a chute into a huge vat of beer. Meanwhile radio announcers ad-lib about the proceedings as if they were sports commentators. When Siam competes with Mexico one of them remarks, “Nobody can beat the Siamese when it comes to dignity, cats, or twins.” Then Serbia goes up against Scotland, Canada against Africa, America against Spain. And it’s not surprising given Maddin’s flair for melodrama that when Serbia vies with America in the final playoff it’s also brother against brother.

What’s sad about Port-Huntly is that she’s missing her legs, amputated years earlier by an alcoholic surgeon named Fyodor (David Fox) after an auto accident caused by her lover at the time, Fyodor’s younger son, Chester Kent (Kids in the Hall’s Mark McKinney), who subsequently emigrated to the U.S. to become a flashy Broadway producer. (The character gets his name from the Broadway producer played by James Cagney in the 1933 Footlight Parade.) But there are even sadder cases. Fyodor, who loved Port-Huntly when he was drunkenly sawing off her good leg and then her mangled one and loves her still, enters the contest under the Canadian banner, playing “The Red Maple Leaves” on an upended piano keyboard to commemorate Canadian casualties in World War I. Chester, down on his luck but indefatigably cheerful, is competing as an American, accompanied by his nymphomaniac and amnesiac girlfriend Narcissa (Medeiros). And Fyodor’s older son, Roderick (Ross McMillan) — a Gloomy Gus cellist who emigrated to Serbia and has returned to compete as a Serbian, hidden behind an enormous black veil — is grieving inconsolably for his dead son (whose heart he keeps in a glass jar, floating in his own tears) and his missing wife, who went into an amnesiac funk when their son died; she of course turns out to be Narcissa.

“I’m not an American — I’m a nymphomaniac,” Narcissa announces to Fyodor, now driving a streetcar, shortly after she and Chester arrive in town. In an equally goofy non sequitur Roderick eventually confronts her with their tragic Serbian past by asking, “Nine million dead, Narcissa — and you won’t even remember one?” By contrast, when he recounts the source of one of his childhood grudges against Chester, his father reproaches him with, “Can’t you ever forget anything?” Compounding the grotesquerie, Fyodor, still hoping to gain the affection of Port-Huntly, makes prosthetic legs for her out of glass, filled to the brim with her beer. But her heart still belongs to Chester.

Chester — refusing to admit to any sadness of his own, even when a Gypsy fortune-teller on the outskirts of Winnipeg forecasts doom for him — is determined to offer the sadness needed for the competition “with sass and pizzazz.” He spells out his can-do philosophy early on: “Sadness is just happiness turned on its ass. It’s all showbiz.” This includes playing gigolo to Port-Huntly and buying up the disqualified musical acts and incorporating them into his own multicultural showstopper — a re-creation, in color, of the “Alaskan Kayak Tragedy of 1898”: East Indian chorines in short-skirted blue Inuit outfits spear papier-maché fish while dancing to the rousing strains of “California, Here I Come,” performed on banjo, panpipe, accordion, clarinet, violin, and sitar, with Chester conducting. Port-Huntly is so delighted with her new glass legs that she decides to make her first public appearance with them in the middle of this number; standing on a rotating glacier, cheerfully indifferent to conflict-of-interest issues, she sets the stage for an appropriately apocalyptic finale.

As more than one Canadian critic has noted, that Chester is Canadian and not American — despite his accent — only enhances the satirical implications of this setup. To be Canadian and consumed with self-hatred means to struggle with belonging to an American colony, existentially if not literally — the colonizing process that matters most is internal. It’s worth adding that just as the success of Port-Huntly’s musical Olympics will be determined by the American market — a fact underlined by the responses of an elderly American couple following it on the radio — the success of The Saddest Music in the World will depend largely on the response of American audiences.

More generally, to be Canadian means to be somewhat lost in terms of identity, which is why Maddin keeps returning to the theme of amnesia — though remembering everything can be just as much of a curse in his tormented universe as remembering nothing. (When Narcissa appears in Chester’s first competitive music number, warbling “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” the smell of her roses sends Roderick into a traumatic, red-tinted flashback, and he relives her telling him of their son’s death.)

Not counting his 2002 ballet film Dracula: Pages From a Virgin’s Diary, this is the first story idea Maddin didn’t come up with himself. Instead, an unfilmed script by novelist Kazuo Ishiguro served as the starting point for Maddin and his usual screenwriting partner (and former teacher) George Toles; an interview with Maddin and Toles in the fall 2003 Cinema Scope reveals that the original was set in London in the 90s and had nothing to do with Canada. Maddin notes that he eliminated the political allegory of the original, whose concerns “were almost entirely about the Third World [countries], comparing them almost to street beggars the way they desperately need charity from the ‘have’ nations.” Toles, who hails from America but lives in Winnipeg, concedes that “there is something to the notion of competitive sadness, people trading away their tragic histories for image, and falsifying genuine tragedy.” He adds, “Also, I’m a powerful Bush hater.”

Yet in his essay about working with Maddin that concludes his 2001 collection A House Made of Light: Essays on the Art of Film, Toles speaks eloquently about the advantages of writing scripts intuitively: “It is frighteningly easy for an evolving narrative to perish under the weight of excessive premeditation or analytic control — the wrong kind of knowing. The imagination is like an oversensitive friend, who can regard any form of inquiry into its secrets as a terrible slight, and who can go into hiding without any warning when it feels betrayed.” This suggests that the implicit commentary in The Saddest Music in the World about the American colonization of Canada is more felt than intellectualized, making it all the more persuasive.

Shot on a variety of film formats that were blended to create a luxuriant, dreamlike, and otherworldly expressionist atmosphere in 35-millimeter, The Saddest Music in the World develops the ongoing Maddin project’s affectionate form of ridicule, making it comparable to Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures. This is most apparent in the way it evokes, develops, and celebrates more than mocks some of the emotional extremes of commercial cinema — making the term “camp” inappropriate, despite the comedy. For instance, some of the musical numbers — Chester’s showstopper, a commercial for Port-Huntly’s beer with a 30s montage sequence — have parodic aspects, but others include ingenious variations on Jerome Kern’s “The Song Is You” that give this plaintive anthem its full emotional resonance. Even the postmodernist and slightly anachronistic way Maddin sometimes mixes his visual effects — such as using a deep-focus 40s noir composition in the midst of a 30s setting with the mazelike bric-à-brac of a Josef von Sternberg interior — has an emotional logic that shows him to be anything but a dilettante. The grief expressed in the story is too keenly felt to be a target of derision; the facts may be cruel and monstrous, but the laughter provoked by them is almost always sympathetic and tender.

The mutilation of Port-Huntly seems inspired by some of the silent films of Lon Chaney, which Maddin wrote about in the winter 2003 issue of Cinema Scope. Chaney was a mainstream “A-list performer” with about 40 starring film roles during the 20s, among them a dozen features that Maddin dubbed “disfigurement allegories,” in which amputated limbs or other physical abnormalities reflect or stand in for “profoundly painful inner wounds.” Maddin writes about Chaney in language that reeks of the mime of silent cinema and the extreme emotions it often trafficked in: “Riding the extreme parabolas of passion permitted by the wild genres in which he worked, he compelled his countenance to seethe, simmer, glower, yearn, lust, and quake in compound permutations of startling virtuosity, creating readable and emotionally complex sentences with the syntax of his features.”

The New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane recently saw fit to scoff at Maddin for being a member of what he called the “derrière-garde” — a curious cause for complaint given that it’s difficult to imagine Lane seeing an avant-garde film and almost impossible to imagine him reviewing one. The truth is, it’s Maddin’s great triumph that he’s a traditionalist to the core, a trait that might seem odd only because the mainstream rarely sees film tradition going back further than three decades — for most of today’s young cinephiles “the movies” started with Jaws, The Godfather, and Star Wars. But Maddin’s style traces the art all the way back to the 19th century, so that, to paraphrase Marlene Dietrich in Touch of Evil, “It’s so old it’s new.” In this respect, he’s much closer to Roderick than Narcissa — condemned to remember in a universe ruled by amnesiacs.