From the Chicago Reader (September 8, 1989). — J.R.

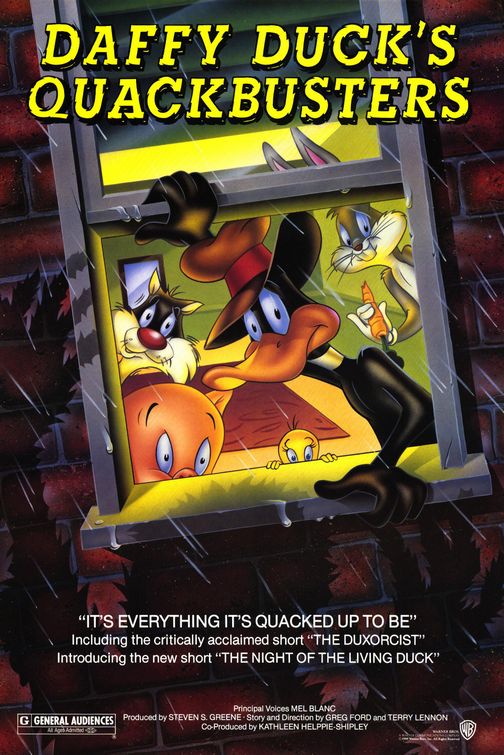

DAFFY DUCK’S QUACKBUSTERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Greg Ford and Terry Lennon

With Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny, Porky Pig, Tweety Pie, Sylvester the Cat, J.P. Cubish, and the voice of Mel Blanc.

It seems more a matter of confusion at Warner Brothers than either poetic justice or business acumen that has denied this triumphant new cartoon feature a theatrical opening in Chicago, although it has recently become available here on video. After a limited if successful run in a New York theater last fall and several scattered theatrical play dates elsewhere in the U.S., Daffy Duck’s Quackbusters has entered the vast no-man’s-land of new features that are available for the most part only on tape, never having received the mainstream attention routinely accorded to other, mainly inferior, Hollywood releases.

Recycled Hollywood classics are very much in evidence right now, in a variety of forms, but this postmodernist conflation — consisting of nuggets from nine earlier Warner Brothers cartoons, two more-recent ones, and a generous amount of new material — displays a critical intelligence and a creative energy that were not apparent in such previous compilations as The Bugs Bunny/Road Runner Movie, The Looney, Looney, Looney Bugs Bunny Movie, Bugs Bunny’s 3rd Movie: 1001 Rabbit Tales, and Daffy Duck’s Movie: Fantastic Island. The principle behind all these earlier efforts was basically cut-and-paste — i.e., string together a bunch of old cartoons with a few new linking segments designed to give them a crude continuity–which meant that the only real function of any new material was to provide setups for the old stuff. Quackbusters, which is much closer to intricate interweaving than cutting and pasting, is more a fresh effort that uses some old material as part of its design. A feature that involves some careful rethinking of the Warners cartoon tradition, it manages to create a new whole so seamlessly constructed that it is nearly impossible for any nonspecialist to tell where — apart from up-to-date topical references — the old animation leaves off and the new animation begins. (The blurb on the video box states that 60 percent of the animation is new.)

The authors and directors of this enterprise are a film critic, curator, and programmer who specializes in Hollywood animation (Greg Ford) and an animator (Terry Lennon). What they bring to it is a conscientious expertise and connoisseur’s appreciation of the best in Hollywood cartoons, as well as an anxiety about messing around with a legacy that is significantly reflected in their plot. The nefarious Daffy Duck inherits the fortune of millionaire J.P. Cubish and uses it to launch a ghostbuster business, hiring Bugs Bunny and Porky Pig as his “associates” (i.e., fall guys), with Porky’s pet cat Sylvester appropriated as an office pet. But the ghost of Cubish expects Daffy to conduct his business honorably, with the ethics of a public benefactor; consequently, every time Daffy begins to display venal and sneaky behavior, the piles of paper currency resting in his Acme office safe immediately shrink in size. The resulting trauma for Daffy — leading to some enjoyably pointed satire of the progreed slant of the Reagan/Bush agenda — recalls the plight of the hero in Balzac’s novel La peau de chagrin, who comes into possession of a wild ass’s skin that makes all his wishes come true but shrinks, along with his life expectancy, whenever it grants a wish.

Not wanting to squander, corrupt, or debase their own Warners legacy, Ford and Lennon have a difficult tightrope to walk — particularly because their own aspirations are entrepreneurial and creative as well as scholarly and custodial. They not only want to guard and sustain the treasured legacy of the classic Warner Brothers cartoon; they also want to adapt and project its virtues into the present and future — which means, in effect, that they’re launching a new business to exorcise contemporary demons while being haunted by the ghosts of vintage cartoons.

Quackbusters was preceded by two all-new cartoon shorts fashioned by Ford and Lennon, The Duxorcist and Night of the Living Duck, both of which are incorporated into the new feature, and both of which, as their titles make clear, feed off relatively recent cycles of horror films, just as Quackbusters itself feeds off Ghostbusters. Night of the Living Duck, which now starts off the feature as a teaser and prologue, was originally intended by the filmmakers to be incorporated into the story proper — just after Daffy is publicly humiliated on TV, and prior to the demolition of the building in which his office is located. (If it had been placed there, one imagines that it would have functioned more as a Walpurgisnacht interlude within the overall scheme of the plot.) The Duxorcist, on the other hand, is now firmly integrated within the Quackbuster plot as the one instance in which Daffy has to go out on an assignment rather than send one of his stooges.

Loaded with intertextual high jinks, Night of the Living Duck begins with Daffy plowing through his collection of horror comics (an idea borrowed in part from Robert Clampett’s The Great Piggybank Robbery, which featured “Duck Twacy”), looking desperately for the comic that continues the story he happens to be engrossed in, when a grotesque alarm clock falls on his head. Then comes an extended dream sequence in which he finds himself in a nightclub as the featured performer, appearing before an exclusive clientele of famous monsters (including the Fly, the Mummy, the Texas Chainsaw Massacre zombie, Godzilla, the Creature From the Black Lagoon, a cyclops, Frankenstein and his bride, Dracula, the Blob, and — just to be perverse — Mad‘s Alfred E. Neuman). Daffy prepares for his number by drinking a bottle of “Eau de Tormé,” and then proceeds in Mel Tormé’s actual voice to sing a likable ditty called “Monsters Lead Such Interesting Lives,” before chatting with the guests and finally incurring Godzilla’s wrath; he wakes up amid his comic books and finds the comic he’s been looking for. Here, too, we find a plot that can be read in allegorical and auteurist terms in relation to Ford and Lennon’s predicament: a preoccupation with continuity (Daffy’s search for the missing comic book, the continuation of the adventure he is engrossed in), which leads to a meditation on the past of characters who now appear to be detached from their original movie contexts (roughly comparable to the clientele at the Ink and Paint nightclub in Who Framed Roger Rabbit — although according to Ford, he and Lennon dreamed up this sequence well before Roger Rabbit‘s release).

The remaining material in Quackbusters — all of it much older and often drawn from selectively rather than inclusively — consists of seven cartoons by Chuck Jones (The Abominable Snow Rabbit, Claws for Alarm, Daffy Dilly, Jumpin’ Jupiter, Punch Trunk, Transylvania 6-5000, and Water, Water, Every Hare) and one cartoon apiece by Friz Freleng (Hyde and Go Tweet) and Robert McKimson (Prize Pest). Some of these, including Claws for Alarm (Porky and Sylvester in a haunted house), Transylvania 6-5000 (Bugs in another haunted house), and Daffy Dilly (the cartoon that introduces J.P. Cubish), are shown either virtually complete or expanded with fresh gags. The matching of old material with new contexts is generally pulled off so smoothly that some transitions occur in mid-sequence or even, on occasion, in the middle of the articulation of a single gag.

At one point in the story, for instance, Sylvester is deposited by Daffy on the window ledge, at which point just about all of Hyde and Go Tweet, also featuring Tweety Pie, is soon under way (along with some fresh material); this ends with Sylvester crashing into a brick exterior, followed, in new footage, by his landing in mid-gag back in Daffy’s office. Elsewhere, a rather bizarre Chuck Jones novelty item from 1952 called Punch Trunk, about a miniature elephant five and a quarter inches tall, is scavenged for a few choice blackout gags relating to a possible Quackbuster assignment. It’s supplemented by an appearance by Daffy on “Zed Toppel’s Frightline,” where, in order to “placate the citizenry” as a leading “metaphysician” and get some free publicity, he scoffs at the very notion that such a creature exists — just as the selfsame elephant traipses across his desk, destroying his professional credibility in front of Toppel and millions of viewers.

Not all of the old material is equally brilliant — Jones’s The Abominable Snow Bunny, for example, is three times as funny as his Transylvania 6-5000 — but the new animation never seems inferior to the archival selections. While the earlier compilations generally attempted to turn the Looney Tunes characters into bland, all-purpose composites — the sort of Bugs Bunny that could stand in for all the various Bugs Bunnys concocted over the years by Tex Avery, Jones, Freleng, McKimson, Clampett, and company — these characters move freely between their many variants, leaping back and forth through about 40 years of cartoon history, without ever sacrificing any sense of character continuity because the transitions are made so carefully and conscientiously.

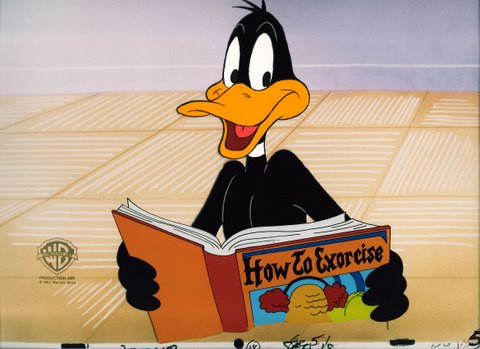

By the same token, one never feels that any of the slight deviations from the Warners tradition represents betrayal or dilution. For example, The Duxorcist features a succession of well-executed and hyperbolic gags that suggest Tex Avery’s 50s work for MGM rather than the more formally pristine work done by Jones, Freleng, McKimson, and others at Warners during the same period. But it is important to remember that Avery was himself a Warners animator between 1936 and 1942, and that he played a major role in developing Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, and Bugs Bunny during this tenure; so the incorporation of a few stylistic traits drawn from Avery’s subsequent work at a different studio — which, after all, grew directly out of his work at Warners — doesn’t really seem inappropriate. Similarly, the use of relatively contemporary topical references — like an exercise book by “Jane Fondue” and the hilarious, American Graffiti-style epilogue that tells us what the various characters are now up to (Bugs in Palm Springs, Porky and Sylvester still lost in the Superstition Mountains, J.P. Cubish still dead, Daffy back to work as a salesman or salesduck) — only encourages us to look forward to further adventures.