The following is a slightly revised and rearranged dialogue recorded for a podcast in January 2014 and reworked a little over a year later for a book by Justin Bozung about Norman Mailer’s films, then cut from the book due to a lack of space the following year. –- J. R.

JUSTIN BOZUNG: My first question for you is, Why in the hell are you and I the only two people in the world that love this film?

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM: Well, we aren’t quite the only two — there’s also my friend Mark Rappaport, who, like Mailer, is both a filmmaker and a writer. But it’s true, there aren’t many others. And I can’t speak authoritatively about why other people don’t like the film, but I will say that I’ve never been a fan of Mailer’s three previous films. And I use the word “film” deliberately and advisedly, because Tough Guys Don’t Dance is above all a movie; it’s the only thing of his that has some resemblance to Hollywood. And he has a flair for it.

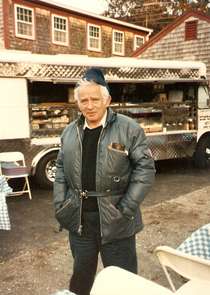

I saw what I believe was one of its first screenings, soon after it was (probably) shown at Telluride, at the Toronto Film Festival. The only time I ever met Mailer was at the press conference there, and I recall saying that it proved he could have made a really interesting film out of his An American Dream novel, which is linked to Tough Guys in several ways. I read that as a serial when it appeared in Esquire in installments, and I’ve always had mixed feelings about it, although I did enjoy some of its cliffhangers. I should also confess that I don’t like the novel of Tough Guys Don’t Dance at all.

BOZUNG: Right — I got that impression from your initial review of the film. I think you said that it was Mailer’s worst book.

ROSENBAUM. Well, I haven’t read all of his books, but it’s certainly the worst one that I’ve read, a tiresome and sluggish potboiler. It’s a tricky thing—I think Mailer is often at his best as a writer when he’s working very close to the edge of delirium, when at any moment it can spill over and become absurd and ridiculous. Ancient Evenings, which I’ve only sampled, is very much in that vein. The notable exception to this rule in The Executioner’s Song, which may even be his best book and isn’t at all like that. I thought it was interesting in the making-of documentary on the Tough Guys Don’t Dance where he takes the rap for the one thing he now considers to be a very disastrous mistake in the film. It’s the scene where Ryan O’Neal is yelling, “God, man, God, man…” (Laughing) Which is hilarious because of how he sees that moment as excessive, unlike everything else in the movie. In the final analysis, I think he winds up agreeing with everyone else about that scene because it isn’t funny. I don’t know why he didn’t just come out and call it a black comedy.

Tough Guys needs to be seen as part of a very special group of offbeat and “excessive” films produced by Cannon over the same period, all of which are hyperbolically personal home movies, in a way — literally in the cases of both Mailer (who shot much of the film in his own house) and John Cassavetes’ Love Streams (1985), which used Cassavetes’ own house. And it’s very nearly that in Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear (1987) — and also, at least spiritually, in Raúl Ruiz’s Treasure Island (1985), which is no less personal.

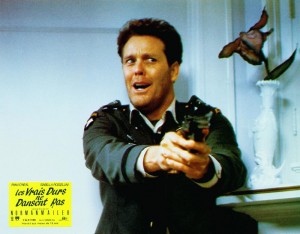

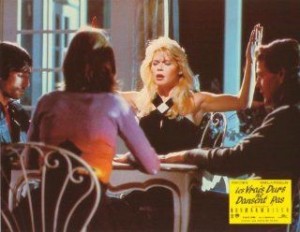

It’s interesting the Mailer calls it a horror movie and a murder mystery, but he doesn’t call it comedy, which is what it is, essentially — and very clearly a comedy in its closing portions. A very black comedy — and there are many things that signal that. Like the mocking use of “Pomp and Circumstance” on the soundtrack when they’re dumping the corpses in the water. Or when Madeline [Isabella Rossellini] shoots Regency [Wings Hauser] off-screen and there’s the line, “Never call an Italian small potatoes” — that’s not something you can possibly take straight. And the very last thing you hear in the film is hysterical laughter…. There is so much hyperbole and excess that people don’t know how to process it; they feel flummoxed — which I assume is why the movie isn’t liked by many people.

What I originally wrote was that the film was like a Russ Meyer film except that instead of the women having big breasts, the men have big egos. But I was wrong, because in fact, all the characters have big egos, women and men alike. I don’t know if it’s fair to call it camp, conscious or otherwise, because that tends to diminish it. But it is very baroque, as the Russ Meyer movies are.

Another film that’s baroque — and it’s a film that everyone else in the world prefers to Tough Guys — is David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986). At the Toronto press conference, Mailer even admitted liking the film and consciously referencing it in one or two shots. But on my list of 1000 favorite films in my book Essential Cinema, I include Tough Guys Don’t Dance and I don’t include Blue Velvet, maybe because of the extreme puritanism at the heart of Lynch that doesn’t hamper Mailer in the same way. It’s not that there isn’t an aspect of puritanism in Mailer. There’s a desire to be disreputable that even goes beyond David Lynch. (Laughing) But there’s nobody who’s innocent in Tough Guys Don’t Dance whereas Blue Velvet is predicated on ideas of innocence.

BOZUNG: It’s difficult for me to digest your comparison simply because of the timeline. Mailer’s book came out a good year before Lynch started shooting Blue Velvet — yet, you can’t deny the coincidences. Both films feature music by Angelo Badalamenti, both star Isabella Rossellini. Blue Velvet opens up with Jeffrey’s father having a stroke, and Tough Guys ends with Regency suffering a stroke…

ROSENBAUM (laughing): I’m sure it made its mark on Mailer before he shot his own movie. The reason why I think Tough Guys is a better film is that it doesn’t pretend to exist in a world of corrupted innocence — everyone is already corrupt from the get-go, despite the fact that Mailer’s mentality sometimes resembles that of a ten-year-old boy perceiving this corruption. It’s amazing how much of American culture in the arts is tailored to and comes from the mentality of ten-year-old boys. It’s in the politics, too. Look at John McCain “seriously” discussing, without any trace of irony, the “good guys” and the “bad guys” in the Middle East, as if it were all an episode in Star Wars or a Roy Rogers western. Maybe because Mailer doesn’t even admit that the idea of innocence exists anywhere in his world is the reason why I find Tough Guys more palatable than Blue Velvet, where there’s a kind of false naiveté predicated on the desire to remain a child. Lynch is more moralistic in his own way, but that also means he’s more simple-minded. In Mailer’s world there are only different forms of corruption — another cliché, to be sure, but for me a more potent one.

BOZUNG: You also mentioned Mailer’s An American Dream earlier. I also see a certain analogy with Tough Guys. Both of the lead characters are in the middle of an existential dilemma, and the dialogue in both is almost Shakespearean…

ROSENBAUM: Again, I haven’t read all of Mailer’s books — I haven’t read The Naked and the Dead, for example. But in the ones I’ve read, every line is pretty fancy, and that’s probably also true in the ones I haven’t read. The there are those weird lines like, “You’re knife…is in…my dog.” (Laughing.) People don’t even say, “Shut up” in this film — they say, “Shut”. It’s all very movie-like — that is to say, performative, as his previous films were, but this time with real direction rather than cinéma-vérité shooting and simply catching things on the fly. The dialogue and the banter go out of their way to do something different and not be clichéd. And there’s also a cinematic intelligence there. One shot that really impressed me is when the camera retreats past the file cabinets in Regency’s office. It’s very powerful, and there are other places that show a real cinematic intelligence.

BOZUNG: Do you ever get the feeling that Tough Guys could be a sort of oneiric dream film? There’s an interview with Mailer that was published around the time of the film’s release where Mailer says that films should be “spooky, dream-like, and visceral”. We get that same aesthetic approach and philosophy with Bergman and Kubrick…. Do you think that was what Mailer was going for with the film?

ROSENBAUM: Well, I don’t want to address his intentions. It’s always a problem when you begin to discuss intentions in any art form. But the film, in terms of the qualities that it has, is very dreamlike. There’s obviously a debate going on inside Mailer between the rational and the irrational, which is also a key element in Maidstone. In the making-of documentary on the DVD, he talks about how if he could re-work the film now, he’d put all the flashbacks at the beginning of the film. Which is a horrible idea, actually. The point is, the flashbacks and how they figure in the film as a whole, don’t make sense at times, such as when the Southern zillionaire [Wardly Meeks III] recounts the story even though he wasn’t actually present at the events shown. It’s very noir-like. It has a surrealistic and fantasy-laden quality as well. He’s borrowing from sources like The Godfather (1972) and Blue Velvet — but also stuff from earlier on in the ‘40s too. It’s as much a noir as it is a horror film.

BOZUNG: It has always reminded me of The Maltese Falcon [1942] in how our protagonist is surrounded by all of these corrupted people who are circling around…

ROSENBAUM: Yes, but not only that film — there are many others involving murder mysteries. Yet most of those films have the aesthetic of being laconic, and this isn’t at all like that. This is very baroque and wordy, but even so, it certainly owes a lot to both Chandler and Hammett.

BOZUNG: Tough Guys also has a very supernatural aura about it. All the characters are steeped in their supernatural beliefs.

ROSENBAUM: That’s right. Which is an aspect that Mailer took very seriously. I don’t. But you see that in Ancient Evenings as well. It’s funny, because in a way he’s very New Age.

BOZUNG: I was watching an interview with you on YouTube recently, and I was curious to hear how much of an influence Mailer has had on you as a writer. You mentioned in the video interview about how when you first started out as a critic you would use the word “I” in your film criticism — and Mailer has often been criticized for doing the same thing in his work.

ROSENBAUM: Mailer did have an influence on me, although in fact, I think where he had the biggest influence — or at least the influence I was most conscious of — was where he never used an “I” at all. When I was writing Midnight Movies with Jim Hoberman in the early ‘80s, I was reading The Executioner’s Song, and it had a very pronounced and direct effect on at least a couple of chapters — on the chapter I wrote about David Lynch and on the one about Sal Piro and the Rocky Horror Picture Show cult. I was using the same kind of third-person storytelling narrative. Also, I tend to like long sentences and Mailer did as well. What I reject and don’t buy into is the ten-year-old boy macho stuff.

BOZUNG: Do you think that comes from his generation?

ROSENBAUM: Well, he was a mamma’s boy. I just find it childish. It also comes from insecurity. He worshipped Hemingway, and you get the same thing in Hemingway too. Some of it’s in Cassavetes as well — all that head-butting.

But I should also admit that the one time I met Mailer, I found him incredibly charming and seductive, and not at all like the blowhards he plays in his first three films. Even so, it’s always been difficult for me to take him at his own level of seriousness. A lot of the stuff he wrote about Marilyn Monroe, for instance, strikes me as ridiculous, and the same goes for most of his other forays into what might be termed film criticism and/or film theory, such as his review of Last Tango in Paris. His ideas about the existential actor, which seem to account for his first three features, seem tiresome, dated, and full of vanity. They’re vanity productions, in fact, although I realize that there are many people who feel the same way about Tough Guys Don’t Dance.

I admire Mailer’s willingness to stick his neck out and his ability to criticize himself, both of which have affected me as a writer, but I haven’t generally been all that sympathetic to his fiction — or his fiction parading as non-fiction, with the notable exception of The Executioner’s Song.

BOZUNG: For me, Tough Guys is a case study or a benchmark in how it could be seen as a film that re-organizes notions one could have about cinema. Mailer breaks so many rules with film itself and its structures. People have it in their heads that a film has to exist via a sort of Syd Field type of three-act structure, and if it doesn’t, then it fails as a film….

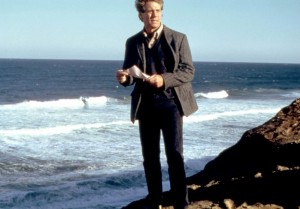

ROSENBAUM: In some ways, Mailer is a real craftsman — in this movie, in An American Dream, and in The Executioner’s Song. Tough Guys is a very intricately plotted film, even though the pacing in the novel didn’t work for me at all. And as Mailer himself says, the performances in the film are very good. But they’re also very weird. You can say that as a director Mailer encouraged them to over-act in the same way that he encourages himself to over-write. There is a kind of vision that he has of American sickness, and it makes it all poetically justifiable in a way.

The only point when you can say that craft is thrown out the window is at the end, when Madeline shoots Regency off-screen. We aren’t told how we get from there to the final sequence when Madeline and Tim are entering the zillion-dollar mansion. Regency’s death isn’t explained; we’re not supposed to worry about any of that. The film wants us to cut to the chase. It’s very ambiguous, and both mocking and cynical. It’s as if Mailer is saying, “It’s the American dream, they got what they wanted, and isn’t it creepy?” It’s not about redemption. Because everyone is corrupt from the start — and this is in Russ Meyer, too — it’s a very jaded view. These aren’t innocent people waiting to be destroyed, and that in itself is very unusual.

BOZUNG: The females in both Tough Guys Don’t Dance and in the world of Russ Meyer are extremely masculine entities…

ROSENBAUM: Yes, and it’s interesting to speculate how this seems to grow out of the war experiences of both Mailer and Meyer — the idea that everyone is corrupt and that the women are even more mythical and super-human than the men. Mailer admitted that the conception of the Isabella Rossellini character was always to be a masculine woman.

BOZUNG: For me, the musical cues are totally ironic and seem to play into that notion of “American sickness”.

ROSENBAUM: And there’s a similar ambiguity regarding whether something is supposed to be taken seriously or as camp in Blue Velvet. But I think what discredits Blue Velvet is all the stuff with the robin and the corrupted innocence suggested by it. I think Lynch intended this to be sincere, but after people took it as camp he allowed people to think of it in that way. I suspect that something similar might have happened with Mailer on Tough Guys Don’t Dance, which would help to explain why he resisted calling it a comedy.

BOZUNG: Looking back at the critical responses to it, it seems like there was a genuine struggle for the critics in trying to classify it. Ultimately, it’s a film that you can’t restrict to a single genre.

ROSENBAUM: Right — that’s an important part of its achievement. It has that particular exuberance, which is also characteristic of Mailer’s writing at its best. It’s also interesting because of that, because it’s rare when you get a real sort of transference of the qualities of a writer and a novelist to cinema. I think the film belongs with Mailer’s written works, quite unlike his previous features. An American Dream, like Tough Guys Don’t Dance, is based on ideas drawn from Hollywood. Even if he had those Hollywood ideas when he was making Wild 90 (1967), Beyond the Law (1968), and Maidstone (1970), they certainly don’t come across that way because of their shooting and editing styles. I think he was very smart to get John Bailey to shoot Tough Guys Don’t Dance, making it a classy movie. Maidstone may be about mise en scène, but Tough Guys actually has it.