One of my first long reviews for the Chicago Reader (September 11, 1987). Reseeing the movie almost three decades later, shortly before being flown to New York to be interviewed about it for a Japanese documentary, I liked it even more, and would give it four stars if I was reviewing it today. — J.R.

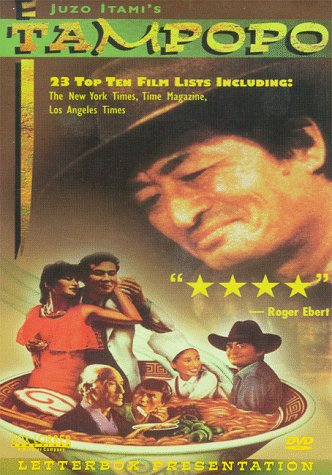

TAMPOPO

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Juzo Itami

With Tsutomu Yamazaki, Nobuko Miyamoto, Koji Yakusho, Ken Watanabe, Nobuo Nakamura, and Mariko Okada.

True, we eat to preserve ourselves from dying. But cooking, the moment of preparing foods . . . is a pause in the most relentless of natural processes, a moment when the process is retarded, when the food exists as itself, no longer a dead thing, not yet assimilated to a living thing. It exists in a moment out of time, and can therefore become a source of esthetic pleasure — small, fleeting, often deceptive, yet a true esthetic object. So brief is its moment of objectivity, this bit of food, that it quivers with the life it came from and with the life it goes toward — and yet, always, it partakes of a stillness that transforms time. The raw stuff has become food — worked upon, transformed by love and care, made proper with a name — and it is a part, if of a stew, of all other stews ever made and ever yet to be made. It partakes of the true Platonic stew. It is a miracle made by a cook to circumvent decay and death, in the quiet knowledge that the task is impossible.

Is that not a true task, and an admirable one? — Paul Schmidt

Tampopo, the second feature of Japanese satirist Juzo Itami, is a comedy about opening a noodle restaurant and about “the last movie” we see when we die — two subjects the filmmaker finds intimately interconnected. More precisely, it is about food and sex and death, implying a metaphysical continuum, and about obsession, which equally implies a well-ordered universe, a world without irrelevance.

No less importantly, Tampopo is a social satire about contemporary Japan — a fact that proves to be more intimidating than the film’s philosophical dimensions, because we never can be confident that we’re catching all the meanings. Even though Japan has clearly bypassed us in economic importance and technological influence, we remain a lot further from Japanese culture than Japanese spectators are from the West. One strong indication of this is Tampopo itself, which abounds in sly digs at the ways in which Western styles of life and thought have invaded Japan. Examples of the latter range from countless Hollywood parodies — a fistfight establishing friendship à la Howard Hawks, a sentimental song among vagrants suggesting John Ford, a cowboy hat worn in a bathtub evoking Dean Martin in Some Came Running, a training regime out of Rocky — to the flashy French dress worn by the eponymous heroine (Nobuko Miyamoto, the director’s wife) when she goes out to eat with Goro (Tsutomu Yamazaki), her principal mentor in noodle preparation.

The film charts Tampopo’s eventual mastery of the art of ramen (Chinese noodles — a Japanese fast-food craze roughly akin to pizza in the U.S.), but there is nothing remotely Zen-like about her progress. Looking straight at her target throughout–unlike the Zen archer, who hits every bull’s-eye only after he learns to look away from it — Tampopo is closer in her maniacal persistence to The Hustler‘s Fast Eddie (Paul Newman), who says at one point, “Anything can be great–bricklaying can be great — if a guy knows what he’s doing and why and can make it come off.” Her fanatical single-mindedness gently mocks the Japanese belief that there is one correct way of doing things, a notion that Itami has ridiculed elsewhere (in The Funeral, his first feature, he showed middle-class mourners studying instructional videotapes on how to behave correctly at a burial). But at the same time, he gives Tampopo’s obsessive quest for the perfect noodle a distinctly American inflection, making her the sister of Fast Eddie and other all-American diehards.

So when Itami calls Tampopo a “ramen Western,” he may be referring to something more than a Hollywood genre. In a recent interview with Clyde Haberman in the New York Times, he points out that noisily slurping noodles in Japan is not only socially permitted, but virtually required. Consequently, when we see a prissy teacher of table manners (Marika Okada) in Tampopo instructing her female pupils in a restaurant in how to slurp spaghetti silently, only to be disrupted by a man doing the reverse at a nearby table, the movie is incidentally making fun of yet another kind of Western influence.

Tampopo’s quest concerns food, but neither sex nor death; a widowed mother, she is a career woman through and through. Instead, the three obsessions are combined in the nameless gangster in a white suit (Koji Yakusho), accompanied by his equally white-clad mistress (Fukumi Kuroda), whose story is interlaced with Tampopo’s. We meet him in the opening scene, when he sits down with his moll in the front row of a movie theater, before a sumptuous array of food. Facing the camera, he proceeds to address us, attacking the practice of eating during movies and similar kinds of distractions, and then describing “the last movie” we see when we close our eyes just before we die — another form of savoring that, like eating and moviegoing, requires total concentration.

Periodically through the course of the film, we encounter the dandy and his mistress, exploring the hedonistic delights of sex and food combined — the erotic possibilities of salt, lemon juice, sour cream, eggs, and seafood are among the highlights. Finally, he’s shot down in the street. Joined by his mistress, he enjoys one last conversation about slicing open wild boars for the yams that they ate — a meal that they never got around to sharing — then closes his eyes and bids her adieu because “my last movie is starting.”

This stylish pair make an interesting contrast in social class with the working-class milieu of Tampopo and Goro (a truck driver). But the gangster and his moll aren’t the only upper-class characters or narrative digressions in the movie. Like Buñuel’s equally satirical The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Phantom of Liberty, which are largely concerned with the same obsessions, Tampopo playfully and delightfully breaks free from the convention of following a single story, spinning out clusters of mini-plots and incidental characters whose narratives illustrate other aspects of food, sex, and death, both individually and in various combinations. After the gangster dies, Tampopo’s restaurant opens and Goro drives away in his truck; the camera pans from the highway to a mother suckling her baby on a park bench, and the film’s circle is complete. For a baby, sex and food, love and nourishment, are indistinguishable; it is only proper adults who learn to segregate them — which is one possible reason why Itami makes his hedonist hero a gangster, and segregates him from the rest of the movie.

Other digressions are like miniature essays on subthemes, such as food and deception (two con artists trying to fleece one another in a restaurant), food and poverty (a visit to friendly gourmet vagabonds in a park), and food and guilt (a man rushes home to his dying wife and asks her to fix dinner; she promptly does so, serves him and the kids, and drops dead with a smile; the father tearfully demands that the crying kids continue to eat, out of respect for their mother). Because many of the actors are well known to Japanese audiences, and some are associated with classic directors — Goro was the kidnapper in Kurosawa’s High and Low, the teacher of table manners was the heroine’s kid sister in Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon, while the older of the two con artists, Nobuo Nakamura, was an Ozu regular since Tokyo Story and also played in Kurosawa’s Ikiru — we can’t hope to follow all of the nuances and implications that helped to make this movie a hit in Japan.

But the wealth of Itami’s humor and invention is such that we never have a chance to feel deprived. His stylistic palette and sense of fun are so wide-ranging that he can oscillate between brightness and darkness to articulate one gag (milking the climactic suspense when Tampopo’s mentors finally sample her perfect noodles, before giving their verdict), and plaster his actors with beet red makeup to punch home another (the embarrassment experienced by conformist executives in a French restaurant when their knowledgeable younger colleague orders differently from the rest of them). One restaurant scene shows a swallowed bone being retrieved with a vacuum cleaner; while we’re still recovering from that, the customer whose life is saved shows his gratitude by treating his saviors to a special meal, one which involves cracking open and bleeding a turtle on the spot.

To all appearances, Itami’s shocks and eccentricities are neither surrealist commando tactics like those of the late Shuju Terayama nor political challenges like those of Nagisa Oshima, but simply the means of a filmmaker trying to tease out the fullest potentialities of his subject matter. The Funeral was equally satirical without being as formally adventurous, and reportedly the same thing applies to A Taxing Woman, Itami’s third feature, a comedy about tax evasion, slated to appear shortly at the New York Film Festival. (Itami seems to be carrying on a family tradition — he’s the son of Mansaku Itami, a pioneer scriptwriter and director known for his mockery of feudalism in period films made in the 30s.) But it’s important to bear in mind that the most valid formal innovations are generally those that spring into being in order to express an otherwise inexpressible content; the often unorthodox inventiveness of Tampopo registers like the dividend of a filmmaker who has found his ideal subject. A gourmand and amateur gourmet cook, Itami has also been a commercial artist, magazine editor, amateur welterweight boxer, band organizer, essayist (one of his collections, Listen, Women!, sold over a million copies), talk-show host, translator (of William Saroyan, among others), and actor (in movies ranging from 55 Days at Peking and Lord Jim to The Makioka Sisters and The Family Game); the broad tapestry of Tampopo suggests some of this range. As someone who embarked on his first feature when he was around 50, he seems to have tasted a good many of life’s possibilities, and this film testifies to his gusto.

In the quotation that began this review — drawn from an essay about the cookbooks of Alice B. Toklas, M.F.K. Fisher, Julia Child, and Adelle Davis, by a writer who has incidentally doubled as stage director and actor, translator of Rimbaud and Khlebnikov, poet, novelist, Russian scholar, professor, and gourmet cook — the suggestion is made that food belongs in a continuum stretching between life and death and encompassing art. Marco Ferreri took some steps toward exploiting this notion in La grande bouffe (1973), without neglecting sex as part of the package; but he was hampered by the linear form and gluttonous implications of his plot, which followed the progress of one ongoing gargantuan meal, as a group of friends studiously ate themselves to death. Itami, by extending the concept of a smorgasbord to the very form of his film, parcels out his wit and wisdom in finely turned hors d’oeuvres — and we don’t have to worry about indigestion when it’s over.