This was written in early 2003 for Trafic no. 46, their summer issue, where it was translated into French by Jean-Luc Mengus, their managing editor. It’s part of a very wide range of “letters” from cities around the world that they’ve been running for many years. It’s very sad to report that Alexis A. Tioseco, whom I’d recommended to the magazine as the perfect person to write their “Letter from Manila,” was in the middle of fulfilling that assignment when he was murdered. — J.R.

Letter from Chicago

Dear Trafic,

Approaching my 60th birthday and the sort of self-definition that stems in part from the various places I’ve lived, I’ve recently noted that I’ve been anchored in the same place for roughly the first quarter of my life (Florence, Alabama) as well as the past quarter (Chicago). Yet it seems equally significant that two-thirds of the remaining half of my life have been spent in New York, Paris, and London, where the world is measured and perceived quite differently from the ways it’s encountered in either Florence or Chicago. This includes the world of cinema, which has figured for me as a distinctly separate entity when viewed from the separate vantage points of these five localities.

As the grandson and son of movie theater exhibitors in Florence, I had an unprecedented access to the hundreds of films shown there every year, and because the world and the world of cinema for a child in Florence basically consisted of what arrived there, my childhood largely consisted of an exploration of the world through the equivalent of a cinémathèque. By contrast, my past 15 years as the first-string film critic for the largest local alternative weekly newspaper, the Chicago Reader, has been experienced as a much narrower activity -— despite the fact that I probably see at least as many films and, thanks to the resources of a large city, the range of my choices is unquestionably wider. (To cite two examples: although I saw many revivals and even a few foreign films with subtitles in Florence, I didn’t see Citizen Kane or any silent film until I went north. Today, of course, thanks to video, such a difference is no longer necessarily operative.)

Another reason why my experience of cinema in the 1950s was more intense and less mediated than it is today obviously relates to the different meanings that cinema had for everyone half a century ago. In contrast to the critical pronouncements on the state of contemporary cinema that meant something to me in the 60s and 70s, those that I’ve encountered in recent years have less and less relationship to any discernible truth. The reason for this — the impossibility of any spectator today seeing more than a tiny fraction of what gets made, compounded by a much more decentralized cinematic climate —- should be obvious, especially if one considers, for instance, the quantum leap in production made possible by digital video and the various divisions between the discourses circulating around mainstream film, cult films, art films, experimental films, and academic film studies. Yet to all appearances, critics prefer to proceed as if these problems didn’t exist, subscribing to a myth of universal visibility and accessibility that is virtually indistinguishable from studio propaganda.

To some degree, of course, such a myth has always existed. For instance, “the cinema” as most western critics were defining it in the mid-70s didn’t include Iranian films, despite the fact that substantial work such as Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black and Ebrahim Golestan’s Brick and Mirror already existed by the mid-60s and Abbas Kiarostami had already made nine films by 1976. But the disparity between the known and the unknown was even then not as glaring as it has become today, where the disparity could more accurately be described as being between the potentially known and the unknowable.

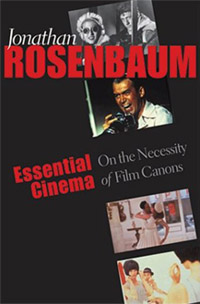

I made an interesting discovery recently about what it means to draw up a list of favorite films. Putting together a collection of my pieces called Essential Cinema: On the Necessity of Film Canons, I added, as an appendix, a list of my 1000 favorites. The point was to cite not the works I considered most historically important but the ones that still provide me with the most pleasure and edification, made between 1895 and the present. My biggest worry before starting the list — that I’d wind up weighting the list more in the past than in recent years —- proved to be mainly groundless. Between 1924 and 2002, the year represented by the fewest titles was 1937, where I came up with only five. Four other years —- 1926, 1939, 1942, and 1945 —- yielded only six apiece. The peak year proved to be 1955, which had 21 titles, and judging by the title-counts of the other years, there was a steady rise up through the 50s followed by a decline in the 60s and then a leveling off: 17 items in the teens, 72 in the 20s, 95 in the 30s, 103 in the 40s, 160 in the 50s, 133 in the 60s, 130 in the 70s, 129 in the 80s, and 125 in the 90s.

Undoubtedly this list is inflected in many ways by my own life-span —- such as the facts that I’ve probably seen more films in the 50s than in any other decade, and that I’ve had many fewer occasions to see those made in previous decades. But the common belief that movies as an art form peaked in the 60s and 70s and then tapered off drastically after that wasn’t supported by my own figures, which showed only a slight decline between 1960 and the present. Does this make me a sucker for contemporary movies? According to the cinema-is-dead people, it must. But I would argue that when most old fogies wax ecstatically about films seen in their youth, it’s largely their youth that they’re ecstatic about, and the films often gain in stature because of that association. What was great about the 60s and 70s in my opinion is that those were the two decades when most people in the West outside France were finally culturally licensed to take films seriously; before and after that, the business dominated —- or dominates — the discourse to such an extent that taking films seriously was (or is) often made to seem like a delusional aberration.

Of course, it’s also a truism that the closer you get to the present, the likelier it is that a favorite will subsequently be forgotten. This is no doubt what Harold Bloom has in mind when he argues that it’s the sifting-out of time and history that establishes canons, not critics. But since it’s a combination of the business and the critical discourse — both determined by people rather than impersonal forces — that does a good deal of the sifting, by making cultural items available or unavailable, valued or devalued, that shouldn’t let any of us off the hook. If I could see all the possible contenders for the best films of 1920 in 2003, the list I’d come up with would have at least as much to say about 2003 as it would about 1920 — probably more, in fact. By the same token, what I can see in 2003 from all periods in Chicago has something to say about Chicago, and therefore “America”.

***

What does it mean to live somewhere that’s “in between”? It’s isn’t simply that Chicago, a Midwestern city, is neither on the east coast nor on the west coast —- and that it’s neither a “one-company” town like Washington, D.C. or Hollywood nor a “communications center” like New York or Los Angeles. To fly from here to New York or Los Angeles or San Francisco isn’t a short hop, and given the size of the Midwest, it even takes several hours to drive from here to Iowa City or Bloomington, Indiana or Madison, Wisconsin. One might simply resolve this issue by saying that Chicago -— to a far greater extent than the east and west coast cities, and for better and for worse — is simply America, and all that this implies. Unfortunately, this makes Chicago to some extent an abstraction and a platitude, both for those aforementioned cities and for other places outside the U.S. Or, to put it more snobbishly, being “in between” means being nowhere. That’s the way if it often seems to me — speaking as someone who typically spends a quarter of every year traveling, and who regards Chicago less as a city to explore than as a place to work.

But being nowhere is very close to being everywhere, and to speak about “America” often means to enter a fantasia and to indulge in the worst rhetorical excesses, whether one happens to be a George W. Bush or a Parisian intellectual. This is undoubtedly a problem that plagues all generalizations about large countries that appear to mistake themselves for the world (including, I suspect, this generalization), encompassing such unwieldy and poorly defined entities as China and Russia as well as the U.S. The passion to catalogue infecting such American writers as Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Theodore Dreiser, Thomas Wolfe, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg on the subject of America is only one symptom of the compulsion to fix the unfixable in a formula. Practically speaking, it means one can make almost any generalization and find some support for it, and in this respect the abstract term “America” is not so different from other unfixable and unknowable metaphysical entities that are widely discussed today as if they were concrete and known, such as “American cinema” or –- for that matter -— “cinema”.

To return to specifics, Chicago, as the third largest American city, is commonly treated by the American film industry as much less important —- or at least demographically less relevant — than either New York or Los Angeles. This has had certain positive as well as negative consequences. The main negative result is that, even though most of the big studio releases open everywhere at once, the majority of art films, foreign films, and so-called independent films premiere in New York and/or Los Angeles and either arrive in Chicago several weeks or months later or —- in certain cases when they’re received poorly in those cities -— never reach Chicago at all.

On the other hand, although it’s disagreeable in many cases to have one’s viewing (and reviewing) choices determined by the tastes of critics at the New York Times and The New Yorker, most of whom aren’t even cinéphiles, one is still spared some of the less interesting American independent features through this winnowing-out process. And seeing some films later than critics in New York or Los Angeles may be beneficial in other ways, making it easier to accumulate information (perhaps the most neglected single ingredient in criticism), to meditate on films seen much earlier at festivals, or to respond to other critics.

Because Chicago is relatively ignored by the industry —- regarded more as nowhere, everywhere, or anywhere than as somewhere — its film critics and film audiences are somewhat freer from the pressures of publicists. The audience is freer because the role of fashion is reduced, and the critics are somewhat freer insofar as they’re sometimes regarded as more populist — neither trend-setters like those in New York nor inside dopesters like those in Los Angeles. Furthermore, the fact that much fewer films are shown in Chicago than in New York means that those that are shown often get more attention. In New York, major films often come and go so quickly that they’re barely noticed at all —- something that’s less likely to happen here. And some of the most important “marginal” films are more welcome in Chicago than they can ever expect to be in New York. John Gianvito’s epic and beautiful 168-minute The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001)–which I regard as the most important feature about the effects of the Gulf war on American life, and which still has no U.S. distributor —- screened at festivals in Austin, Taos, Buenos Aires, Chicago, and many other places in the U.S. and Europe, and even returned to Chicago for a commercial run, long before it appeared in New York, where it had very little impact. And this case is hardly unique either for the U.S. or the present period; to follow the career of Marcel Hanoun in France over the past half-century, for instance, is to witness the same sort of critical apartheid.

There’s an organization here that calls itself the Chicago Film Critics Association, founded significantly by a publicist not long after I moved to Chicago in 1987. Many large American cities have such groups, whose main function is to award prizes to films and individuals at the end of every year, and I used to be a member of this one, until I decided a few years ago that its system of awards was predicated on a certain kind of bad faith. The same large companies that refuse to open many films in Chicago until weeks or months after they’ve opened in New York and Los Angeles routinely send out videos and DVDs of those films at the end of every year, hoping that Chicago critics will place them on their ten-best lists or award them prizes in spite of the fact that they haven’t yet opened locally. For me, this is a flagrant example of using critics as part of advertising campaigns, and because I feel that I owe more allegiance to my readers in Chicago and the films that they see than I do to the companies, I’ve refrained from participating in this game, which typically assigns many prizes to films long before they open. Moreover, I believe that the taste of the public is often better than that of the Chicago Film Critics as a collective body — especially because most of the members of the latter live in the suburbs and typically come to Chicago to attend press screenings of a small handful of foreign films every year —- so that the awards wind up serving a regressive function comparable to the Academy Awards, essentially rubber-stamping a few films that already have been accorded a great deal of attention.

A much more serious local group is the Chicago Film Seminar, an informal gathering of film scholars who are mainly but not exclusively academics and who meet once a month at the School of the Art Institute. A paper is read, followed by a respondent and a general discussion, and then most of the members have dinner together at a nearby restaurant. Since the main participants of this group include Tom Gunning, Miriam Hansen, Chuck Kleinhans, Yuri Tsivian, Virginia Wright Wexman, and many distinguished out-of-town visitors, as well as graduate students and such local nonacademic cinéphiles as Fred Camper, Ray Privett, and Martin Rubin, the overall level of discussion is both sophisticated and critical while remaining relaxed and collegial. Gunning, Hansen, and Tsivian all teach at the University of Chicago, and I tend to associate their scholarship with much of the best work being done presently in film history. Moreover, the fact that Tsivian’s commentaries on Eisenstein and Vertov are now available on DVDs and are in some ways even more impressive than his published work highlights the exciting fact that some of the best film scholarship currently available anywhere —- which also includes in France, for example, the work of Bernard Eisenschitz on Vigo —- has suddenly become available within mainstream culture, to be purchased at Tower Records or Virgin Megastore outlets. This is decentralization in the best sense, for scholars and audience alike.

Chicago has, I believe, the oldest film festival in the U.S., now approaching its 39th year, and possibly the oldest university cine-club (Doc Films, at the University of Chicago, which operates seven days a week and has by now become such an institution that the more modest cine-club at Northwestern University -— at the opposite end of Chicago, in the northern suburb of Evanston —- now calls itself Block Films, thanks to being located on the campus’s Block Museum of Art). It also has the largest outlet in the U.S. for foreign and independent films on video, Facets Multimedia, which also operates a small art cinema.

The festival is not one of the most distinguished, at least in comparison to those in New York and San Francisco, but it is still one of the largest, commonly showing at least a hundred features a year, and for this reason it can more easily accommodate important works without certain social or “professional” credentials such as Gianvito’s (for me, an “amateur” film in the very best and most worthy sense) than the New York festival, which typically limits its roster of features to about two dozen. Similarly, Doc Films may have a smaller national profile than the film programs at the Museum of Modern Art or George Eastman House, but its tradition of being a hotbed for the kind of auteurist taste spearheaded by Cahiers du Cinéma in the 1950s has made it a kind of school and workshop for such knowledgeable cinéphiles as Dave Kehr (my predecessor at the Reader, who subsequently wrote for the Chicago Tribune and then the New York Daily News before settling at the New York Times).

***

Perhaps it’s indicative of something that both Roger Ebert and I work from a Chicago base and that, in spite of our radical differences, we’re still friends, because in New York and Los Angeles, the spirit of competition between critics is much more pronounced. Ebert is usually perceived as the most powerful and influential film critic in the U.S., while my own audience basically consists of a particular slice of the Chicago public: the half-million or so people who read the free alternative weekly I write for, the Chicago Reader, in either its city or suburban editions, and those who read me on the Internet — an audience whose size I’m less aware of, although it is certainly as international as one could wish, given the emails that I receive regularly from readers around the globe.

Much as film and other media in the U.S. are defined for most people by the degree of their exposure, film criticism is also generally defined by the size of its audience rather than by any other credentials. Knowledge about or sensitivity to cinema counts for very little alongside one’s rapport with the mass audience, so that the “best” film critics are commonly regarded as those whom the audience and studios (who, thanks to the Academy Awards, are commonly perceived as synonymous) are likeliest to agree with. Late last year, a minor flurry was caused by an editorial in Variety by Peter Bart expressing an overall disdain for film critics due to the fact that their ten best lists differ from one another and, even worse, from the box office charts and the Academy Awards. Significantly it was only critics who visibly took offense at Bart’s complaint; the expectation of consensus in the media is by now so widespread — at least among media spokespeople, who presume to speak for everyone — that it appears to match George W. Bush’s assertion that anyone who doesn’t agree with American aggression is automatically an enemy. (As recounted recently in The New Yorker by Hendrik Hertzberg, “The other day, Secretary of State Colin Powell was reminded that his boss is in bed by ten and sleeps like a baby. Powell reportedly replied, `I sleep like a baby, too –every two hours I wake up screaming.’”)

Unfortunately, the overseas belief that Bush himself represents the American consensus — in spite of the fact that a majority of Americans didn’t vote for him, not to mention the fact that I’ve never encountered anyone who to my knowledge has participated in a public opinion poll —- shows how fully the mythology of these polls duplicates the mythology of test marketing, and how much both mythologies are subsumed under the compulsion to generalize about essentially unknowable subjects. Indeed, the interfacing of these two forms of self-fulfilling prophecy and propaganda has been operative since Reagan, and it guarantees a kind of false knowledge about what people think about politics and war as well as about cinema that extends far beyond the boundaries of America. In a similar fashion, one might say that a certain “remake/sequel” mentality rules not only the American film industry but the American government: much as the invasion of Iraq (actual or anticipated) has been perceived as a “remake” of or “sequel” to the Gulf War, the absurd escalation of security checks at airports since September 11 has been motivated by the irrational conviction that any remake of or sequel to September 11 will necessarily involve airplanes (rather than, say, shopping malls or apartment houses or freeways).

Furthermore, the various tautologies that determine public perceptions of power guarantee that this power is always circumscribed by a system of values which one could call “might makes right” that is permitted little variation. Thus when Miramax chooses to marginalize some of its own releases by opening them in only one or two cities with little advertising, one can be certain that the national press and the television reviewers will follow their lead and pretend that these films don’t exist; some of the important films that have been completely ignored in this fashion include Through the Olive Trees, the color Jour de fête, and the rerelease of Les Demoiselles de Rochefort–and it’s worth adding that the first two of these films have also never appeared in the U.S. on video or DVD. Consequently, it is paradoxically easier to see many films with no distributor in the U.S. than those handled yet effectively kept from public view by Miramax. Yet it’s also symptomatic of the prestige of power within mainstream journalism that Ebert could recently write in the Sun-Times — after noting correctly, in a mainly sympathetic article about the Tarkovsky Solaris, that Tarkovsky’s films “are more like environments than entertainments” — that “It may be, indeed, that Tarkovsky’s work could have benefited from trimming. A producer with the scissors of a Harvey Weinstein could have deleted hours from his oeuvre, sometimes no doubt for the better.”

As shocking as such a pronouncement may be, it seems to me merely the logical consequence of a situation in which lack of knowledge is deemed less important than the kind of institutional power wielded by a Weinstein (or by an Ebert, for that matter), which is then paradoxically taken to be a form of higher knowledge. It’s a situation with many manifestations and consequences, and to say that it holds sway in Chicago is significant only insofar as Chicago is nowhere and anywhere. Everywhere I go, people still discuss “American cinema” as if it were a discernible object, but as I’ve already indicated, it seems impossible to perceive or identify such an entity independently of the choices made by the major studios in what films will receive multi-million-dollar advertising campaigns —- which means that even to speak of “American cinema” as a real as opposed to mythological subject is to capitulate to the agendas of those companies, which already enjoy a stranglehold on the market. For related reasons, I feel it is no longer possible for any critic in the world to hold forth on “the state of cinema” in any given year or contemporary period without lying, because no one in the world is capable of seeing more than a tiny fraction of what gets made today, and there is absolutely no reason to assume that the best or most interesting or most innovative (or even potentially the most popular) work is necessarily available to the public. To assume otherwise is to capitulate to a kind of presumptuous arrogance that is almost never challenged nowadays, and which is essentially held in place by the largest companies. These companies have by now trained everyone in the media to adopt their choices as “the cinema” —- an efficiently closed system that will occasionally widen only when a small film like The Blair Witch Project unexpectedly and momentarily breaks through the barriers on its way to becoming a “major release”. (Significantly, even The Blair Witch Project was eventually succeeded by a forgettable studio sequel.)

Thanks to this radical suppression, any critic is faced with the task of having to either rationalize his or her lack of knowledge about the state of cinema or else pretend that this lack of knowledge doesn’t exist, and it is almost always the second path that is followed —- to the satisfaction of most editors, producers, and consumers but at the expense of the truth. For lack of knowledge is clearly the great unspoken taboo in criticism; critics are expected to take every precaution to ensure that no one will suspect it becomes a factor in arriving at critical judgments.

Even if it’s no longer possible to say anything conclusive about the state of cinema, a great deal remains to be said concerning the state of discourse about cinema, which is far easier to grasp. Ebert is therefore typical rather than exceptional in his willingness to defer to someone like Weinstein on the artistic legacy of Tarkovsky. To assume otherwise is to enter a zone of uncertainty where art may thrive but commerce is threatened, and in a climate where digital video has ensured that it’s easier than ever to make a film —- yet often harder than ever to show it or see it — power inevitably holds sway over taste; it even becomes taste as long as it can legislate what is and isn’t artistic as well as what is and isn’t visible. Within such a context, it becomes easier to see how the invisibility of Chicago offers a certain freedom. Manohla Dargis, a Los Angeles colleague who’s a former New Yorker, wrote me the other day that the great thing about writing for the Los Angeles Times rather than the Village Voice is that there’s no one looking over your shoulder.

***

If American cinema no longer exists as an integral or graspable subject, it is still possible to speak about American cinemas —- that is, various films, ranging from prominent releases to others surviving in various forms of marginality. It’s even tempting to split these two cinemas into the famous categories proposed by Manny Farber, the white elephants and the termites (Manny Farber, ”White Elephant Art and Termite Art,” Trafic no. 10, printemps 1994),* especially if we associate the grandstanding gestures of the former and the subterranean moves of the latter less with artistic impulses than with the channels of communication and forms of traffic that, existentially speaking, determine their very existence.

From this point of view, my favorite white elephants of the past couple of years would include Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Peter Bogdanovich’s The Cat’s Meow, Todd Haynes’ Far From Heaven, Brian De Palma’s Femme Fatale, Lisa Cholodenko’s Laurel Canyon, David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, Spike Lee’s 25th Hour, and Rick Linklater’s Waking Life. And my favorite termites —- a list less likely to be familiar to French readers —- would include David Gordon Green’s All the Real Girls, James Benning’s California trilogy (El Valley Centro, Los, and Sogobi), Alfred Leslie’s The Cedar Bar, Daniel M. Cohen’s Diamond Men, Stan Brakhage’s Ellipses, reels 1-4 (made in 1998, but first shown in Chicago four years later), Michael Gilio’s Kwik Stop, John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein, and Adam Larson Broder and Tony R. Abrams’ Pumpkin. (I don’t know in which category to place Christopher Munch’s The Sleepy Time Gal, which was seen mainly on cable TV and excluded from most canons as a result, thereby becoming omnipresent and invisible at the same time —- a fate also enjoyed or suffered by most of the films of Charles Burnett, the greatest of black American filmmakers.)

One could of course reshuffle this list and speak of other categories, other cinemas. For instance, regional cinema: All the Real Girls (a love story shot, like Green’s George Washington, in a remote small town in North Carolina), the California trilogy, Diamond Men (focusing on diamond salesmen in Pennsylvania, one of them played by Robert Forster), Laurel Canyon, The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (shot in its entirety in New Mexico), Mulholland Drive, 25th Hour, and even Waking Life (an animated film, but one based on footage clearly shot in and around Austin and Brooklyn) —- though not The Cedar Bar, which in spite of its title, referring to the Greenwich Village bar favored by abstract expressionist painters, mainly consists of found footage intercut with a reading of a play.

Or one could speak about experimental cinema as a broad category (Benning, Brakhage, De Palma, Gianvito, Leslie, Linklater, Lynch) or philosophical and metaphysical cinema (Gianvito, Gilio, Green, Linklater, Lynch, Munch, Spielberg), or deconstructive cinema (A.I., The Cedar Bar, Ellipses, Far From Heaven, Pumpkin, Waking Life). Better yet, one could combine some of these categories to speak about a cinema that demands some initiative from the spectator: obliging us to imagine what it means to go to prison (the principal concern of 25th Hour, which is rarely addressed in American society) or to view A.I. not as a film by Kubrick or by Spielberg but as a film in which Kubrick deconstructs Spielberg and vice versa; creating characters designed to confound our expectations (as in All the Real Girls, The Cat’s Meow, and Laurel Canyon), or creating images that confound our usual distinctions between live-action and animation (Ellipses, Waking Life). In short, one can still carve out meaningful samples of American cinema, even if no one can establish comprehensive maps. And just as Chicago is a huge city that, after 16 years, I can still easily and happily get lost in, I would insist that even the small portion of American cinema that finds its way here is still more than any individual can ever pretend to know.

Cordially,

Jonathan