I just heard the very upsetting news that the great Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi (The White Balloon, The Circle, Crimson Gold, Offside) was deprived today of his passport in Tehran, now making it impossible for him to leave Iran — reminding me, alas, of what happened to Pere Portabella in Franco Spain roughly half a century ago.

The two following short essays were commissioned by the Jeonju international Film Festival in February and March, 2009 and published in a bilingual catalog to accompany a Portabella retrospective held there in May.

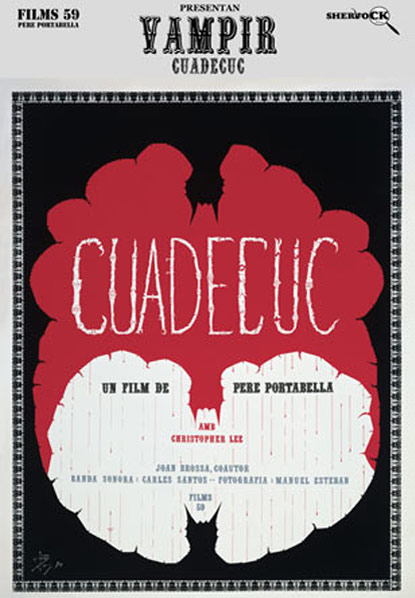

It’s hard to keep up with all of Portabella’s activities these days, but his wonderful web site — which one can access in English, and which grows periodically in leaps and bounds — makes it somewhat easier to try. My most recent visit reveals that it’s now apparently possible to download several of his films on the Internet, directly from this site. I’m still eagerly anticipating the DVD box set that’s still apparently in the works, for which I wrote a commissioned essay (to be printed or reprinted in my next collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia: Film Culture in Transition: see Publications and Events on this site), but meanwhile here are a couple of commentaries about two of his early films — one of which, Cuadecuc, Vampir, remains my favorite of his works to date. –J.R.

Trying to Compute Don’t Count on Your Fingers

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

My first problem in coming to terms with No Compteu Amb Els Dits (1967, 26 minutes), Pere Portabella’s first film, is my inability to distinguish between every one of what he himself identifies as its 28 separate fragments, each one reportedly lasting between 15 seconds and two minutes. Counting the segments myself — not with my fingers, but with a pen, a piece of paper, and a VCR — I come up with only 24, not 28 But then again, the only obvious ways of distinguishing one sequence from another are (a) changes in themes, characters, and/or settings, (b) changes in the music, (c) other changes in the soundtrack involving sound effects, dialogue, or narration, (d) switches between black and white and color (or vice versa), and (e) graphic transitions that are apparently similar to those used in Spanish commercials shown in cinemas during this period. And at one point or another, Portabella seems to defy most of these conventions by eliminating or obfuscating such markers. This is clearly part of his point — pursuing a kind of extension of the Kuleshov experiment presided over by William S. Burroughs (see “The Invisible Generation,” the last chapter in The Ticket That Exploded, a book roughly contemporary with this film), he can put together any soundtrack with any strip of film and find an uncanny match, an unsettling congruence exploited most obviously in the fatuous discourse of commercials. Cinema, in short, is a kind of fraud, and Portabella’s project from the outset is both to expose and to play with its fraudulence, much of it founded on various forms of apparent continuity.

“Defeated. Defeated but not vanquished,” begins the offscreen man’s voice in the first sequence, over black and white shots of a man in a bathrobe touching his own unshaven cheeks and then reaching for a shower faucet. “And when the projector is turned off, the white screen remains,” affirms the offscreen woman’s voice at the end of the last sequence, over a color cameo of a woman’s face. Between these two positive negations, 20-odd other sound-and-image combinations pretend to have and therefore mock various kinds of narrative coherence. Even the longest and most elaborate segments — an incoherent chase thriller intercut with a documentary about a Pepsi-Cola plant, a priest receiving a shave in a barber shop (and then looking out the window at a man emerging from a subway station who removes and eats his own moustache) — the most conventional signifiers are twisted to yield a kind of nonsense.

One bit of mockery, asking us to identify a scene’s “error” (which proves to be written on a character’s forehead), strikingly anticipates American experimental filmmaker George Landow’s no less hilarious Institutional Quality (1967) and its eventual 1976 remake, New Improved Institutional Quality. A swank dinner between an initially estranged upper-class couple echoes and evokes some of the bourgeois decadence explored and celebrated by Luis Buñuel — whose Viridiana Portabella helped to produce, leading to his own (unvanquished) “defeat” before embarking on his own filmmaking — while using both camera movements and tricks with continuity that suggest Alain Resnais’ Marienbad. Some seemingly reasonable monologues gravitate into absurdity (“Nobel invented the cinema”) while others might be said to point towards this film’s own methodology (“If you repeat it often enough, a falsehood becomes an affirmation.”) Through it all, an effort to find of a form of coherence through surreal juxtapositions provides early sketches for both Umbracle (1972) and Pont de Varsovia (1989).

***

Dracula Yesterday and Today: The Poetics and Politics of Portabella’s Cuadecuc, Vampir

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Thanks to an old appointment book of mine, I can pinpoint that my initial encounter with the cinema of Pere Portabella took place at 7 PM on May 17, 1971 during the Cannes film festival, when I first saw Cuadecuc, Vampir. It was showing in the Quinzaine des Réalisateurs (Directors Fortnight) at a now-defunct cinema called Le Français. It’s worth adding that the name of the filmmaker and the title of his film were both slightly different from the way we know them today, for reasons that are historically significant. The name of this Barcelona-based filmmaker was listed as Pedro Portabella and his film was called simply Vampir. Why? Because he was Catalan, a language forbidden in Franco’s Spain, making both the name “Pere” and the word “Cuadacuc” (which I’m told is an obscure Catalan term meaning both a worm’s tail and the end of a reel of unexposed film stock) equally impermissible. Furthermore, Portabella wasn’t present at the screening because, as I later discovered, he was one of the two Spanish producers of Luis Buñuel’s Viridiana one decade earlier, and the Franco government was punishing him for having helped to engineer this subterfuge by confiscating his passport, making it impossible for him to travel outside of Spain. And for those like myself who wondered how a film as unorthodox as this could play in Franco Spain at all, it eventually became clear that it survived, like the Catalan language itself (not to mention Dracula), clandestinely, via secret nourishment.

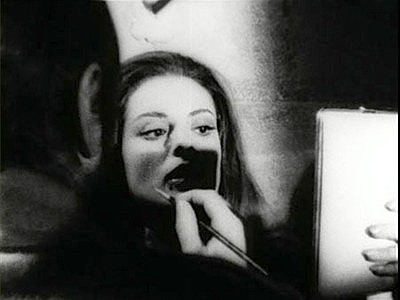

Vampir was my favorite of all the films I saw at Cannes that year. I returned to it several times, and described it afterwards in the Village Voice as “at once the most original movie at the festival and the most sophisticated in its audacious modernism”. A silent black and white “documentary” of sorts about the shooting of Count Dracula, a color feature, by Jesus Franco with Christopher Lee, Herbert Lom, and others, it had a remarkable nonsynchronous soundtrack composed by Carles Santos consisting of such varied materials as a barking dog, a jet plane, a pneumatic drill, an operatic aria, a recurring and sumptuous piece of Muzak, and various sinister-sounding electronic drones. (The only use of synchronous sound occurs in the final sequence, when Lee himself in his dressing room, over two separate takes, eloquently describes the death of Dracula in Jonathan Harker’s novel.)

Thanks to both Santos’s witty aural accompaniments and many of the film’s camera movements — which pass back and forth between the story of Dracula and various details exposing the artifice of the Franco film being shot —- the film creates a ravishing netherworld that seems to exist in neither the 19th century nor the 20th but in a unique zone oscillating between these eras, just as it seems to occupy a realm of its own that is neither fiction nor non-fiction. The high-contrast cinematography, moreover, suggests some of the meditative beauty of Murnau’s Nosferatu and Dreyer’s Vampyr as well as the dissolution and decay experienced when we see these films today in fading prints.

There are other ways of perceiving the special poetics — and politics — of Vampir, Cuadecuc. Some have alluded to the subtle ways in which Lee’s Count Dracula suggests Generalissimo Franco by offering a ruling narrative that Portabella’s lyricism periodically escapes and floats free from, just as Jesus Franco also suggests his near-namesake. But above all is an all-embracing sensual pleasure and humor overriding centuries, generic categories, and conventions.