This is one of a series of essays that I wrote in 2007 about four Fassbinder films for Madman, the Australian DVD label. The other three — on Martha, Katzelmacher, and The Bitter Tea of Petra von Kant — can be found elsewhere on this site. —J.R.

I’m still trying to figure out what I think of Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1945-1982). An awesomely prolific filmmaker (he turned out seven features in 1970 alone), he became the height of Euro-American fashion during the mid-70s, then went into nearly total eclipse after his death from a drug overdose –- reminding us that the fates of the fashionable can often be precarious.

Openly bisexual, tyrannical on his sets, and habitually dressed in a leather jacket, Fassbinder cut a starlike figure in the firmament of New German Cinema, though he was hardly alone. If the French New Wave of the 60s was mainly about films, the New German Cinema of the 70s was mainly about filmmakers, and each of the best-known directors had a claim to fame that was mainly a matter of public image: eccentric exhibitionism crossed with German romanticism (Werner Herzog), existentialist hip crossed with black attire and rock ‘n’ roll (Wim Wenders), Wagnerian pronouncements (Hans-Jürgen Syberberg), a dandy’s stupefied worship of shrines and divas (Werner Schroeter), and so on. When it came to Fassbinder, who improbably evoked both John Belushi and Andy Warhol, one was made to feel that the real drama in film after film wasn’t in the makeshift characters or the brightly colored images but in the offscreen intrigues of a baby Caligula manipulating his players and technicians.

As skeptical as I often was in the 70s about Fassbinder as a role model, I’ve been more than a little disconcerted by the speed with which he’s vanished from mainstream consciousness. Having by now seen about two dozen of his 37 features, I find much of his work, for all its deliberate topicality, as fresh now as when it first appeared.

In some ways it may be even fresher, because its meanings are no longer ruled by the same political agendas. Part of my reluctance to join the Fassbinder bandwagon in the 70s stemmed from the critical industry’s unqualified interpretation of his work as left-wing and subversive -– a reading intricately bound up with the rediscovery of Douglas Sirk’s 1950s Hollywood movies by Fassbinder and others. For academics who argued that Sirk soap operas like Imitation of Life were subversive critiques of American life rather than conformist endorsements, some historical sleight of hand was necessary, particularly when it came to dealing with the reception those movies had back in the 50s. Sirk –- a leftist stage director in pre-Nazi and Nazi Germany, and a closet intellectual and campy commercial director in both Germany and the U.S. -– made movies with conservative/conformist as well as skeptical/subversive elements. The former played most indelibly to his producers and his contemporary audiences; the latter tended to be carefully and cynically buried like secret treasures, awaiting discovery by future generations.

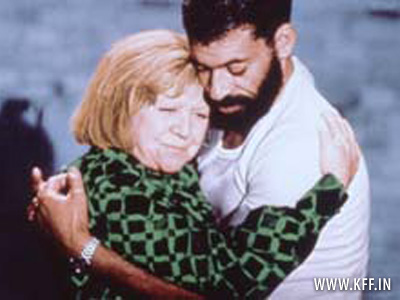

Fassbinder’s growing popularity as an arthouse director may well have peaked with Angst essen Seele auf (Fear Eats the Soul, 1974) — a feature that represented a conscious effort to reach a wider audience than his earlier and more avant-garde and “underground” efforts, and one that was partially spurred by his discovery of Sirk. It grew out of an anecdote told by a hotel chambermaid (Margarethe von Trotta) in Fassbinder’s The American Soldier (1970), about a cleaning lady in Hamburg named Emmi who married a Turkish immigrant named Ali and was later found strangled with the mark of an A from a signet ring on her throat. Fassbinder kept the same basic characters, shifted them to Munich, made Ali a Moroccan instead of a Turk (which raises some nagging questions about how interchangeable Moroccans and Turks might be), and eliminated the grim ending while substituting another one. He also borrowed a few aspects of Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), a tearjerker about the ostracism faced by a middle-aged, middle-class widow (Jane Wyman) who gets involved with her younger gardener (Rock Hudson), outraging her family and social circle. Fassbinder focused on a cleaning lady in her 60s (Brigitte Mira) and a garage mechanic who seems roughly half her age (El Hedi ben Salem), eliminating class difference while increasing the age difference and making the ethnic difference the overriding cause of the couple’s persecution. The film’s subtitle comes from an alleged Arab saying translated into broken German by the title hero. (It was Fassbinder’s second film in a row that used “angst” in its title — the other being Angst vor der Angst, or Fear of Fear.)

The results are far more ambiguous and conflicted than any of Sirk’s social critiques. While Sirk’s couple, in traditional Hollywood fashion, are viewed as entirely admirable and sympathetic, Emmi is an avowed former Nazi who picks a particular Italian restaurant for her wedding dinner because Adolf Hitler once ate there; more generally, she’s frequently shown as being innocent to the point of stupidity. (Ali, though a bit of a simpleton himself, isn’t given any comparably alienating traits, and in fact is much more sketchily drawn as a character.) And the intolerance of Emmi’s family, friends, coworkers, and neighbors towards her boyfriend and subsequent spouse (including an especially xenophobic and sexist son-in-law played by Fassbinder himself), while much more pronounced than anything found in Sirk’s villains — one son even calls her a whore — is eventually mitigated by other factors. Her grocer, refusing to deal with Ali and then ejecting Emmi from his store, winds up becoming friendly again after his wife convinces him that he needs their business. One of Emmi’s sons, who previously kicked in her TV screen after hearing about her marriage to Ali — a glancing allusion to All That Heaven Allows, when the widow’s empty life is illustrated by the way she sees her own reflection on a blank TV screen when her children give her a TV set as an implied compensation for remaining single — later pays Emmi for the damage and apologizes so that he can then ask her to babysit. Emmi’s coworkers, who previously froze her out socially during their lunch breaks because of her relationship to Ali, bond with her again after one of them gets replaced by a recent Yugoslav immigrant, who is frozen out in turn by Emmi and the others. And some of the neighbors overlook their own antipathy towards Ali when they need his help in moving furniture.

In short, Emmi is never idealized; one often feels that Fassbinder is appalled by her intellectually even while he weeps for her suffering. But then you might say that he enjoys being appalled — and might be in some ways as intolerant of fellow Germans as his German characters are intolerant of immigrant workers. He’s also pretty schematic about the way most characters wind up overcoming their biases, but invariably for swinish reasons involving exploitation. (We never see Emmi and her colleagues get beyond their snubbing of the Yugoslav immigrant, but clearly if they ever do, it would be in order to exploit her and exclude someone else.) It could also be argued that Emmi’s temporary breakup with Ali — which drives him back into the arms of a former lover (Barbara Valentin), the owner of the bar where they met — is precipitated largely by her refusal to cook couscous for him, which the bar owner gladly offers to do. So “simple” intolerance is far from the whole story. Consequently, when critic Thomas Elsaesser writes that “Fassbinder constructs his storyline with the purity of a fable and the emotional impact of tragedy,” I can find myself agreeing only with the second half of his formula. Impurity is even one of this film’s most salient traits. But then again, it’s the film’s impurity that allows for its greatest triumphs — above all, getting us to accept the implausible romance that develops between Emmi and Ali, which Fassbinder can do only through shifting stylistic strategies. When their initial encounter on a dance floor is stage-managed for obscure reasons by the usual crowd at the Asphalt Bar (which seems no less improbably to consist of Germans, Turks, and one Arab), he reverts to the highly stylized and painterly iconography of his Katzelmacher (1969). But as soon as the couple’s mutual interest is sparked, he switches to a more naturalistic mode that allows the actors to embody their characters rather than simply suggest them.

“After seeing Douglas Sirk’s films I am more convinced than ever that love is the best, most insidious, most effective instrument of social repression,” Fassbinder wrote in a memorable essay in 1971. The fact that he wrote “best” instead of “worst” is entirely characteristic of his bitter misanthropy, which relishes the traps and suffering of his characters even as it implicitly lodges protests against them. Sadomasochistic impulses are at the heart of most of his films, and the tricky task of squaring those impulses with some kind of attack on sociopolitical oppression is what has often makes it difficult to come to terms with his work politically. Yet Fassbinder’s provocative statement about Sirk is another seductive formula that doesn’t work once one tries to apply it to Ali — even if it does apply to other Fassbinder films (perhaps most notably Martha) — because the love between this couple is virtually the only thing that this film chooses to show positively and without a trace of sarcasm.

Both Fassbinder and Sirk tended to deal with characters incapable of understanding their own social victimization and, more often than not, unable to change. (Beware of spoilers ahead.) Regarding these doomed characters with ironic compassion, their films were arguably more defeatist than progressive, because their sophistication consisted chiefly of recognizing corruption and stupidity, not of imagining situations where they might be overcome. Even when love eventually seems to conquer all in Ali, the title hero’s fate still appears to be doomed once he develops a stomach ulcer from all his worry — a condition that his doctor says is characteristic of immigrant workers. In this respect, Todd Haynes’ Far from Heaven (2002), a much closer remake of All That Heaven Allows, could be described as more progressive than either of its predecessors — even though being progressive about the American 50s half a century later is considerably less daring than offering any sort of contemporary critique in any period.

The worlds that both Sirk and Fassbinder conjured up resemble more stylish versions of the repressed world found in W.C. Fields comedies -– bounded on all sides by irritations and petty frustrations. (”There are no lighthearted moments in any Fassbinder film that I can recall,” Gary Indiana once wrote. “If a character’s happy, it’s because he hasn’t yet heard the bad news.”) Fassbinder differed strikingly from Sirk in focusing much more often on working-class and petit bourgeois characters, and in putting more teeth into his bite, but the sense of entrapment was no less pronounced.

Sirk’s stylistic hallmarks included theatrical uses of lighting, color, framing, and mirrors, and his thematic hallmarks included blindness; in the most general terms, one could say his movies were all about ways of seeing and not seeing. Fassbinder’s self-conscious and low-budget appropriation of such hallmarks made them at once more overt and more overtly campy, so that contemporary readings of Fassbinder films were fully in tune with their critical attitudes in a way that contemporary readings of Sirk films were not. I’ll never forget a late-70s lecture on All That Heaven Allows and Ali: Fear Eats the Soul given at the University of California — San Diego by filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin. Like a Mystery Science Theater 3000 kibitzer, Gorin offered plenty of hilarious voiceover wisecracks about the Sirk film while it was playing, but he didn’t dare submit Ali to any equivalent sort of irreverence.

Yet on reflection, it’s entirely possible that contemporary readings of Ali , however hip, oversimplified or factored out many of its contradictions and conflicts, for at least two reasons — the overtouted relation to Sirk, and the power of the two lead performances, both of which tended to make viewers overlook other elements. Which is another way of saying that the film’s emotional impact triumphs over what might otherwise be perceived as intellectual confusion and stylistic impurity. Consider all the complexity conveyed in Mira’s facial expression after Ali says good morning to her following their first night together — or even just the way she eats a banana during her lunch break while the other cleaning ladies are spouting racist invective. Or consider the way that El Hedi ben Salem, in a more minimalist performance founded mainly on presence and telegraphed feelings, plays off of Mira (including the proud grin he allows himself while taking a shower after she praises him for his looks). For all his hatred of humanity, Fassbinder really loves his unlikely couple, and I think we wind up remembering this heartbreaking pair long after we’ve forgotten the plot or the argument.