I no longer recall where this was written for and/or published, but I’m pretty sure it was written in 2004. Eight years later, having just seen Far from Afghanistan at the Toronto film Festival — a film that John Gianvito organized, shot a portion of, and edited, playing a role somewhat comparable to that of Chris Marker on Far from Vietnam — I’m reminded yet again of how irreplaceable and precious John is to to the conscience and, yes, endurance of American cinema. — J.R.

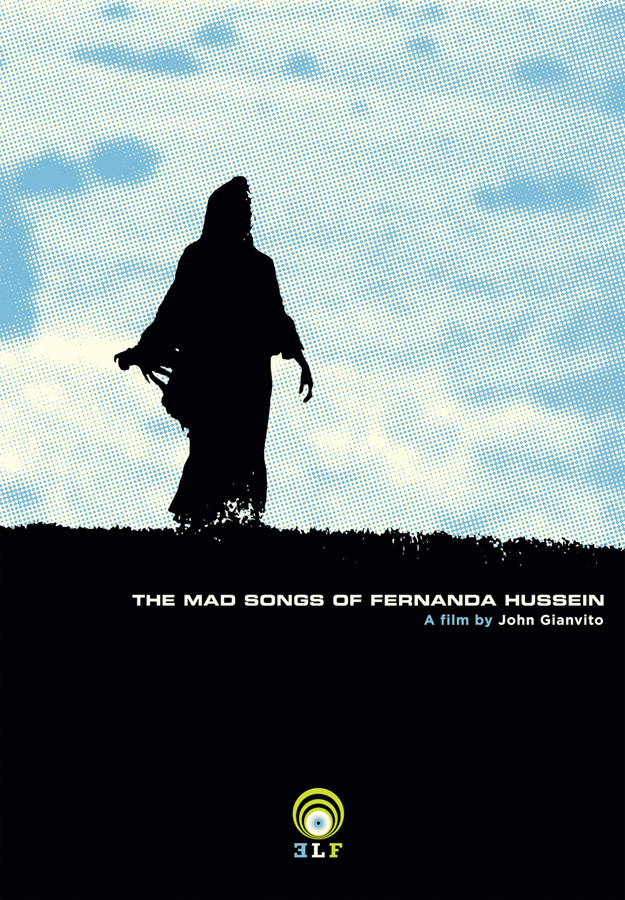

A rare act of bearing witness, The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein is the only film I know that gives ample voice to the rage and despair felt by many Americans during the Gulf war —- a loose, disparate, disorganized, and virtually invisible group of individuals in which I’d include myself. Many of us are experiencing comparable emotions at the moment, after September 11 and the terrifying fantasies of consensus that have followed, most of them involving present and future American invasions and conquests.

All this gives John Gianvito’s 168-minute feature an urgency that he couldn’t have anticipated when he finished the film early last year. It also makes me feel grateful personally, in a way that goes beyond critical approval, if only because it proves to me and several others that we aren’t alone. Because one of the most suffocating aspects of American life in periods like these is to frustrate, discourage, intimidate, and silence certain dissenting thoughts and emotions, it’s hardly surprising that this film has no mainstream credentials in the U.S. It still lacks a distributor and has not yet had a single New York screening, although it’s already been shown at film festivals in Austin, Chicago, and Taos (among many others), as well as in Argentina (where I was on a jury that gave it a prize), Greece, Holland, and Portugal; it has also elicited praise from such filmmakers as Chantal Akerman and Peter Watkins, both of whom have expressed personal feelings of recognition similar to my own. For all those who feel empathy for what it expresses, it has the status of a precious secret.

I have a friend — a journalist and performance who writes for the so-called alternative press and considers herself a leftist. She was exuberant during the Gulf war, which she said reminded her of World War 2 — an event she’s too young to remember, although she speaks about it with nostalgia, almost as if she were remembering a favorite movie. The war in Afghanistan gratifies her imagination in a comparable fashion because it makes her think of spies and various intrigues. During the Gulf war we both lived in Chicago; now she lives in New York, and I only had to worry about steering clear of her bloodlust when I briefly visited the city after the New Year. I keep thinking about her when I reflect on America in the Middle East, not simply because of her innocent callousness but because I periodically regard her as a friend. I also remember my mother and both my brothers, whom I feel much closer to, supporting the Gulf war when it was happening —- though they mainly feel differently now —- to the point of not minding the “collateral damage” of killing innocent people just as long as they were Iraqi and not American.

Many have said that the obliteration of then World Trade Center was “just like a movie,” and I think some of them regard the carnage in the Middle East the same way, only without the bitter aftertaste of being forced to realize that it isn’t a movie after all. The Mad Songs was made for people who feel differently, much as The Best Years of Our Lives was made for returning veterans and their families after World War 2. It could be argued, of course, that the William Wyler film has superb acting and cinematography and Gianvito’s film doesn’t. Its only professional actor is Thia Gonzales in the title role, and truthfully The Mad Songs remains an amateur film, even if it’s an amateur film in the best sense (a category including, among others, Jean Cocteau, Robert Kramer, and Jean Rouch).

Shot over six years in New Mexico —- not because Gianvito lives there, but because he wanted a desert setting —- the film focuses on three characters in separate cities, stories that rarely intersect: the Mexican-American of the title who acquired the name Hussein through marriage and loses both her children as a consequence; a rebellious and angry teenager who leaves home and becomes an activist; a scarred returning soldier (played by an actual veteran of the Gulf war).

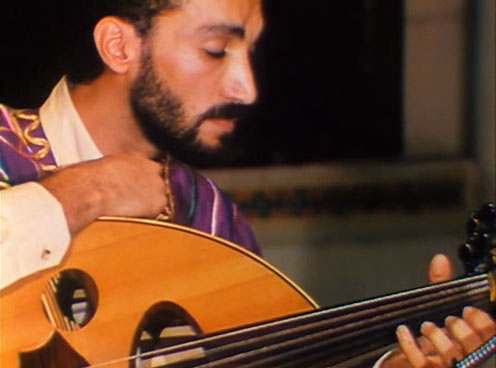

By virtue of being nonprofessional, Gianvito is free to mix documentary with fiction, a love for silent cinema and landscape (he works as associate curator for the Harvard Film Archive, and also teaches — a fact reflected in his cameo in the film) with music (most notably, extended passages by Iraqi musician Naseer Shemma commemorating some of the war’s victims) and dialogue, a taste for blistering satire (in the remarkable sequence devoted to war toys) as well as convulsive and cathartic tragic lyricism (in the extraordinary final sequence, at once tribal and experimental in its poetic meditation on ritualistic violence). Ironically, with an almost Whitmanesque inclusiveness and restlessness, he can make me feel proud to be an American again.