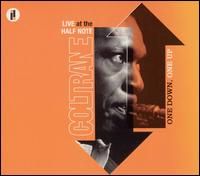

This was originally posted on November 22, 2010. Seeing the excellent, informative, and often moving documentary Chasing Trane, which curiously includes more interview material with Bill Clinton than with McCoy Tyner, led me to repost this. — J.R.

On volume 2 of this superb two-disc set (One Down, One Up: Live at the Half Note), recorded on Alan Grant’s “Portraits in Jazz” radio show on May 7, 1965, is a spectacular 13-minute piano solo by McCoy Tyner on “My Favorite Things” that covers well over half of the number’s almost 23 minutes. This solo is incidentally bracketed by some of Coltrane’s loveliest soprano-sax glisssandos on disc, but what amazes me about Tyner’s cascading tour de force is not only how he keeps it going in unforeseeable directions, but also how many different directions this consists of — tonal and atonal, rhythmic and melodic, calm and frenzied — and how steadily it builds to Coltrane’s second solo.

What follows is the final draft of a treatment for a documentary about Tyner that I coauthored via email with cinematographer John Bailey in late 2001 and early 2002, at the behest of producer Rick Schmidlin, with and for whom I’d worked as a consultant on the 1998 re-edit of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. This treatment went precisely nowhere, but it did lead to a very lengthy conversation with Tyner about various ideas for the film when he was in Chicago on a gig, after which I mailed him a video of Charles Burnett’s When it Rains, a particular favorite of mine, as a model for a film that was attuned to jazz aesthetics. As I recalled to Tyner at our meeting, I had attended many sessions of him playing with Coltrane, Jimmy Garrison, and Elvin Jones at the Half Note in the mid-60s, and part of what remained with me was how concentratedly these musicians listened to one another, as if in a trance. Musicians listening to and watching other musicians is for me the great and usually neglected cornerstone of what jazz documentaries should be; my two main examples of this are Charlie Parker listening to Coleman Hawkins and Buddy Rich in a never-completed Gjon Mili documentary, and Billie Holiday watching and listening to Lester Young in The Sound of Jazz. [11/22/10]

The Real McCoy: A Proposal

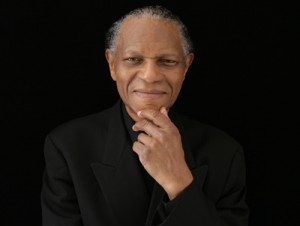

In a dramatically lit closeup, McCoy Tyner recounts how as a teenager in Philadelphia he would often see Bud Powell, the greatest of the bebop pianists, in his own neighborhood — and how Bud would even come over from time to time to play McCoy’s piano, not having one of his own. McCoy’s voice continues offscreen over an overhead shot of the piano keys as he plays one of Bud’s up-tempo tunes, such as “Cleopatra’s Dream” or “Parisian Thoroughfare,” with his trio in a studio setting. For the first few seconds, without hearing anything, we see only his powerful hands on the keys, moving in slow motion so that we can follow their precise movements and articulations. Then, as the film whips up to normal speed, his fingers become a fast blur, at the same time that the music’s sound volume is raised so that we can finally hear the playing —- a driving, pounding, up-tempo scorcher with accompaniment by bass and drums (which we see, along with a fuller view of Tyner, as the camera moves back and we cut to many different angles).

At this point Danny Glover, a good friend of Tyner, introduces himself as offscreen narrator and begins to tell us what Tyner’s teenage years were like — meeting John Coltrane for the first time, and getting his first serious gig with Art Farmer and Benny Golson’s legendary Jazztet — while John Bailey’s camera roams freely over period photographs, down city streets, into long-forgotten clubs, recording studios, and haunts.

These three opening segments sum up the overall direction that The Real McCoy is to take in terms of both style and content: a singular survivor in the jazz world, framed in a timeless space of memory and reflection, recalls how he entered, developed, and made it there; in the highly theatrical space of a studio, club, or concert hall we hear him play, and watch him and his fellow musicians play and listen to one another, without the distraction of voiceovers; then Glover’s voice leads us into the engrossing details of McCoy Tyner’s odyssey —- his long stint as John Coltrane’s irreplaceable pianist, and his subsequent development as a leader of his own groups, a composer, and an arranger.

The film will be broken into seven parts, each one beginning with a segment featuring interviews and vintage footage to tell another chapter (narrative or thematic) in McCoy’s story, followed by a complete performance. The chapter headings will include such topics as “Beginnings,” “Coltrane,” “McCoy Tyner Plays Duke Ellington,” “Monk, Powell, and Tatum,” “Passion Dance,” “McCoy and the Latin All-Stars,” and “Jazz Roots”. Each of the musical segments will feature a different lineup with many of the greatest jazz musicians alive. (Tyner’s prestige is such that he’ll clearly have the pick of the crop.) Each will be shot in a different location: the club in Philadelphia where McCoy first met Coltrane (still active and available); Rudy Van Gelder’s legendary studio in Englewood, New Jersey where McCoy, Coltrane, Garrison, and Jones recorded their classic quartet sessions. Other possibilities include the Village Vanguard, the Blue Note, the Monterey Jazz Festival, and perhaps even a concert in Havana, where Chucho Valdez has invited Tyner to perform.

Throughout this documentary, the music will comprise the “action” and story while the biography of Tyner will introduce elements of reflection and context to set these numbers up. And any film that’s about listening, as this one will be, will also be about looking — predicated on the philosophy that the way one looks at musicians already helps to determine the way one listens to them.