From the Winter 1984/1985 Sight and Sound. Only years after writing and publishing this essay, I recalled seeing a test reel of Cinemascope with my father at an Atlanta movie exhibitors convention in 1953, part of which included a refilming of the “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” number in CinemaScope. I have no idea whether this still exists, but it may help to account for why some people misremember or wrongly identify the entire film as being in CinemaScope.

For those who might be puzzled by the third illustration from the end, this is Dominique Labourier’s character performing in a nightclub in Céline et Julie vont en bateau, in a sequence that precisely parallels the courtroom sequence in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. — J.R.

First Number: “We’re Just Two Little Girls from Little Rock”

I don’t believe in the kino-eye; I believe in the kino-fist. — Sergei Eisenstein

Before even the credit titles can appear, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell arrive to a blast of music at screen center from behind a black curtain, in matching orange-red outfits that sizzle the screen — covered with spangles, topped with feathers — to look at one another, toss white ermines toward the camera and out of frame and sing robustly in unison. As electrifying as the opening of any Hollywood movie that comes to mind, this jazzy materialization so catches us by surprise that we are scarcely aware of the scene’s fleeting modulations as the dynamic duo makes it through a single chorus. The black curtain changes to a lurid blue, then a loud purple; the two women twice exchange their positions on stage while gradually dancing down a few steps; and the complex flurry of gestures they make toward each other — all gracefully dovetailed into Jack Cole’s deft choreography — makes the spectator feel assaulted by them as a team as well as individually: a double threat.

As awesome a demonstration of kino-fist strategies as anything in Potemkin, this opening to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is just the first in a series of rude shocks. The second comes only moments later — after the credits have appeared over the same stage curtain and an offscreen choral version of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” (in a passage of relative respite, during which we’re shuttled through no less than seven more garish color changes) — when, after “Little Rock” resumes, the film cuts from Monroe singing solo to a reverse angle of a tuxedo-clad Tommy Noonan watching, waving, and wanly blowing a kiss from a cabaret table. The lumpy, passive, decisively unheroic presence of Noonan in the shot — as the film viewer’s uninvited surrogate, as a neuter/neutral surface off which the dynamism of Monroe is allowed to ricochet— creates a dialectical montage of collision, like lightning striking a plateful of mush, as jolting in its way as the first apparition of Monroe and Russell.

Henceforth, all Howard Hawks’s cards are on the table. The viewer is warned that the unbridled spectacle of his two female stars and the flabby repose of male reaction shots comprise the dialectical limits of this film’s cartoon universe, and the only equals to be seen anywhere will be the two stars themselves. Indeed, in a world where competition and corruption are taken for granted, their noncompetitive friendship forms a united front that is the film’s only moral center.

If we pause, finally, to consider the words of their song, the notion of spiritual kinship becomes even more striking when we realize that they’re assuming precisely the same identity. They begin as “two little girls from Little Rock” who “lived on the wrong side of the tracks.” But after Monroe takes over to describe how, after “someone” broke her heart in Little Rock and she “up and left the pieces there,” she eventually drifted to New York with a more hardened view of men and what she wanted from them, Russell promptly becomes the “I” in the same narrative: “Now one of these days in my fancy clothes/I’m going back home to punch the nose,” before they end in unison, “Of the one who broke my heart . . . in Little Rock.”

In effect, though neither Lorelei Lee (Monroe) nor Dorothy Shaw (Russell) has yet been introduced as a character, the movie is already offering both as Lorelei the gold digger. If we check back to Anita Loos’s 1925 flapper novel, which provided the original source material, written in the form of Lorelei’s diary, we discover that she’s the only one who comes from Little Rock, and her departure is precipitated specifically by shooting an unfaithful lover. Yet with a magical transmutation made possible by musicals, the movie Lorelei is accorded not only a softer center but a spiritual essence multiplied by two, and distributed equally to Dorothy.

Hawks is famous as the director who never once deigned to film a flashback, and the pasts with which he furnishes his characters before their screen appearances are generally scanty. Sometimes this involves an unhappy love affair, as in Only Angels Have Wings and Rio Bravo; here it is dispensed with as quickly as possible, vaguely to motivate Lorelei’s gold digging, and then just as quickly dropped so that the rest of the movie can bask in the immanence of a continuous present tense. The thing to stress is that the absence of any narrative discontinuity between song and story makes the numbers a form of being for both characters rather than acting; and within this being, Dorothy is quite willing to assume or share Lorelei’s identity, without warning, explanation, or regret.

While Hawks’s only pure musical might conceivably be the most popular of his movies today, critics on the whole tend to be confounded by it. Treated only marginally in books devoted to the director, it has received attention more recently from feminist writers, who often disagree about essential characteristics. For Maureen Turin (“Gentlemen Consume Blondes,” Wide Angle, no. 1), it is sexist, racist, and colonialist; for Lucie Arbuthnot and Gall Seneca (“Text and Pre-Text: Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” Film Reader, no. 5), it is jubilantly feminist and, at least by implication, proto-lesbian. Molly Haskell (“Howard Hawks,” in Cinema: A Critical Dictionary), no less persuasively, finds it “as close to satire as Hawks’s films ever get on the nature (and perversion) of sexual relations in America, particularly in the mammary-mad 50s.”

Like the blind men grasping different parts of the elephant, each of these writers is on to something — which helps to explain why the movie manages to accommodate some of the viewpoints and fantasies of heterosexuals and homosexuals of both genders. If doubts remain (as with Robin Wood, Gerald Mast, Leland Pogue, and Donald Willis in their Hawks books), these mainly have to do with the lackluster male leads, Noonan and Elliott Reid. But Richard Dyer in Stars goes further and, in judicious detail, finds incoherence at the very heart of the film, in the figure of Lorelei as played by Monroe: “a quite massive disjunction” between the innocence of Monroe’s image and the calculation of Lorelei’s character: “This is not a question of Lorelei/Monroe being one thing one moment and another the next, but of her being simultaneously polar opposites.”

Insofar as Lorelei/Monroe is perceived as an isolated character, Dyer’s point is irrefutable. But seen as an integral function in a diabolical machine that also incorporates Russell, Noonan, and Reid, she projects a coherence and legibility that is as sharply defined as theirs. In fact, the movie’s innate capacity to suggest readability and unreadability, feminism and sexism, optimism and pessimism, beauty and grotesquerie at one and the same time makes it the ideal capitalist product, malleable to every consumer need: a distillation of Hollywood which is also a parody of same, a calculated/innocent excess of effect which rewards characters and spectators equally so that everybody gets what they think they want.

This may help to explain why a striking number of contemporary viewers, Maureen Turin among them, misremember the film as being in CinemaScope, that standard-bearer of 1950s amplitude. Admittedly, it was released by Fox only a few months before the company unleashed CinemaScope with The Robe and How to Marry a Millionaire, the latter of which had both Monroe and a related theme. But one is tempted to add another reason for this error, which is aesthetic: that Gentlemen Prefer Blondes has the overall effect of the process without actually using it. Try imagining, for instance, the final shot — Reid, Russell, Monroe, and Noonan all facing the camera and wedding altar, with plenty of space between them — and the format naturally imposes itself.

***

Second Number: “Bye Bye Baby”

The movie’s plot — the exploits of Lorelei and Dorothy as they sail from New York to Paris and back again on the Île de Paris — both elaborates on the essence of the five musical numbers and gives the viewer a chance to recover from the last while preparing for the next. Lorelei, single-mindedly in search of money, is sent to Paris with a letter of credit by her wealthy fiancé Gus (Noonan). Dorothy, single-mindedly in search of love (or sex), is given a free ride as Lorelei’s chaperone, while Gus’s skeptical father hires private detective Malone (Reid) to spy on Lorelei and report any indiscretions . . . While the stars board the liner, along with members of an Olympics team who immediately arouse Dorothy’s interest, they repair to adjacent staterooms. Dorothy is joined by the relay team and others, Lorelei by Gus with parting gifts, and two versions of “Bye Bye Baby” soon get under way.

In Hawks’s nonmusicals, songs usually figure to celebrate groups and allegiances that have recently formed: Jean Arthur and flyers in Only Angels Have Wings, Barbara Stanwyck and nightclub patrons in Ball of Fire, Lauren Bacall and Hoagy Carmichael in To Have and Have Not. Here the same process is at work, starting from the warmth that spreads between Dorothy and the relay team and radiating outward. But, oddly enough, Dorothy is again singing a song that makes sense only for Lorelei, who is saying goodbye to Gus. Dorothy has invited the team and their friends into her room for a party, and after taking a few dance turns with one athlete she starts to sing her euphoric farewell — irrationally — to several of them in turn, before they respond as a chorus and some of their women friends follow suit.

Perhaps these women are seeing off the team, which gives the male and female choruses, if not Dorothy, some reason for singing the song. But the scene immediately follows an “intimate” scene between Lorelei and Gus and seems to relate to them even more, although they are now absent from the shot. Lorelei’s repeated use of “Daddy” as her pet name for Gus, delivered in Monroe’s inimitable baby talk, makes her or Gus the “baby” of the subsequent song more than anyone else, although the sentiment gets weirdly displaced.

A plea for faithfulness couched in the paradoxical form of a spirited lullaby, the song would be wholly logical only if Gus sang it to Lorelei. But Lorelei has just subverted this theoretical possibility by teasing Gus that he “can be a pretty naughty boy sometimes,” thereby turning the tables and forestalling any such charges on his part. And as soon as Dorothy and her party complete their two choruses, it is Lorelei who sprints Gus back to the privacy of the next cabin to sing a slower, more sultry version of the same tune.

Seeing Monroe really turn it on — tripping her finger up Gus’s lapel, caressing his shoulder and forcing him to keep close eye contact with her while he blushes and blanches — one is irresistibly reminded of Chaplin with his female victims in Monsieur Verdoux, confidently running glissandos up and down his own sexual narcissism. The exchange of sex (or its promise) for capital is equally brazen in both characters, and the fact that in each case it is being performed by a charismatic star — Chaplin near the end of his reign, Monroe at the virtual onset of hers — makes it register with a decidedly Brechtian aftertaste. (If Monroe and Chaplin are equally predators, the spectator surely qualifies as part of their prey.) Hawks is again using Gus as a cartoon stand-in for the leering spectator in the stalls, but by folding this unsettling equation into the middle of Dorothy’s good-natured altruism, he removes the potential sting from the insult, confuses the issue.

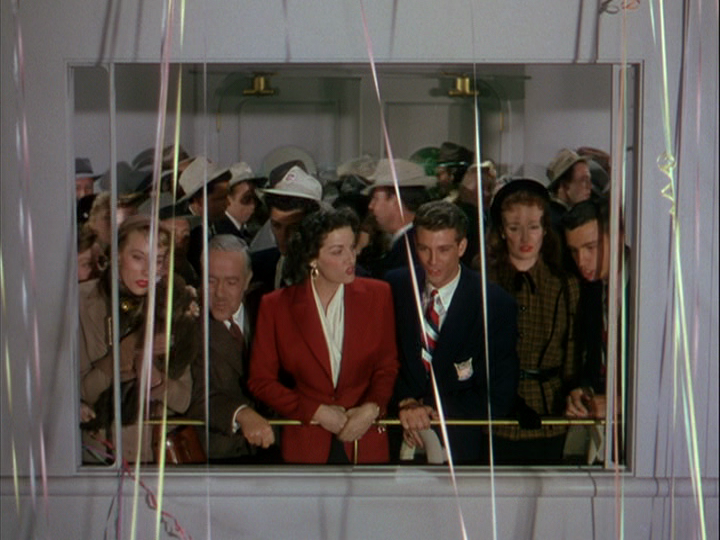

Sure enough, as Lorelei is about to conclude her vamp version, Dorothy, now the delighted observer, slaps the wall to announce her presence, Lorelei returns the song to up-tempo, and the crowd joins in for a final chorus. The ship’s bell rings, a voice calls out “All Ashore” and the whole happy company — Gus and Lorelei, Dorothy and party — race to the deck amid festive streamers. By the time Lorelei’s voice briefly prevails over the others as she prepares to bestow on Gus a farewell kiss (accompanied, as usual, by cartoon sound effects to indicate his swooning response), her inspired if cold hypocrisy has fused indistinguishably with Dorothy’s bland if warm sincerity, so that each becomes an untroubled facet of the other. Here and elsewhere, they jointly project a true image of artificiality or an artificial image of the truth — the two possibilities are collapsed into a single aggressive personality, looking for men.

If it seems that the lumpy male spectator has just been sent packing, this turns out to be only half true. Just as Dorothy is always ready to take over for Lorelei, so Detective Malone, as lumpy and unstarlike as Gus, is waiting on board to take over as male spectator surrogate. Like Dorothy, he is less identified with wealth, hence more “normal” in the film’s terms. But the distinction is only superficial: for most of the movie, he protects the interest of Gus and his father as faithfully as Dorothy protects and defends Lorelei.

***

Never have two women gotten along together so well in a musical. — Norman Mailer

Central to the achievement of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is the extraordinary rapport between Jane Russell and Marilyn Monroe, which constantly enhances the interaction between Dorothy and Lorelei. This notion of documentary imposed over fiction is related to Hawks’s flair for instilling a relaxed atmosphere on his sets. One recalls the real romance that developed between Bacall and Bogart while shooting To Have and Have Not, the graceful incorporation of Dean Martin’s drinking in Rio Bravo. In the latter film, John Wayne’s acute embarrassment when faced with Angie Dickinson’s underwear seems to express the discomfort of the actor as well as of the character. Indeed, apart from the flat villains in both films, one could argue that Walter Brennan is the only prominent actor in either who constructs a wholly fictional character; the others are treated more generally as house guests.

It is worth noting, therefore, that Monroe and Russell actually became friends while working on Gentlemen Prefer Blondes — despite the fact that Russell was paid $200,000 for her part (and got top billing), while Monroe, on her Fox salary and not yet a star, got only $500 a week. Hawks once explained their unusual “chemistry” as screen presences by describing Monroe as a fantasy and Russell as “real”. Mutatis mutandis, this anticipates the strategy of Hawks enthusiast Jacques Rivette two decades later, in pairing the cartoon- like Juliet Berto with the more theatrically trained and earthbound Dominique Labourier in Céline et Julie vont en bateau. (Not coincidentally, the two French actresses were already friends.) To understand the curious logic of either film, the personality crossovers and theatrical impersonations, one ultimately has to see the two actresses as the dialectical yet compatible sides of a single female character, and all the men in the cast as variations on a single male character.

***

Third Number: “Ain’t There Anyone Here For Love?”

As soon as the trip is under way, Lorelei, under the watchful eye of the eavesdropping Malone, checks the passenger list for “suitable” (i.e., rich) escorts for Dorothy. “I want you to find happiness and stop having fun,” she insists, objecting to Dorothy’s current interest in the Olympics team. Dorothy proceeds to the indoor pool and gym where, surrounded by muscular athletes, she learns that they all have to be in bed by nine. A whistle summons them to their exercises and a male chorus begins to count to four to start them off. The number that follows reverses the premise of the last two by privileging the viewpoint of a female spectator, Dorothy, and isolating her from Lorelei.

A retreating camera exposes a screenful of bulging male flesh traversing the frame in various exercises, and Dorothy proceeds to deliver her up-tempo query/lament while threading her way through a labyrinth of indifferent bodies. For the most part, she seems as alienated from this dehumanized spectacle as they are from her, and the few desultory glances she gives, whether skeptical or entreating, are all met by equivalent blank stares. In some early shots, one glimpses a group of female oglers and women in the pool, the latter of whom Dorothy addresses; around the middle of the number, the camera isolates her in frontal close-up, underlining her apartness. But near the end, when she stoops near the edge of the pool so that athletes can dive over her, she gets knocked into the water, which quickly reintegrates her into the surrounding community. A group of men hoist her out and onto their shoulders; a waiter serves her a drink, and, as she finishes the song, she and the men have resumed friendly eye contact.

In short, her song passes through four forms of address — to other women, to herself, to the camera, to everyone — while implicitly addressing itself also to an offscreen Lorelei, whose infantile absorption in money seems equivalent to the loveless narcissism on display here. Yet the sheer physicality of this campy, materialist sequence is merely the culmination of a trait that has characterized the film so far: the cramming of massive bodies (or masses of bodies) into the frame. Practically every shot has featured the commanding bulk of the stars, the self-effacing (shy or secretive) bulk of the two male leads, and/or teeming crowds of extras, and the gym number is only clarifying this profusion of bodies by making it more blatant and functional. Trying to reconcile the contrary drives toward narcissism and friendship, the film uses these bodies along with diamonds (bulk versus glitter; warmth versus cold) as props in a philosophical debate between Dorothy and Lorelei which the mise en scène is continually expounding.

***

Fourth Number: “When Love Goes Wrong, Nothing Goes Right”

If we can’t empty his pockets between us, we’re not worthy of the name Woman. — Dorothy to Lorelei

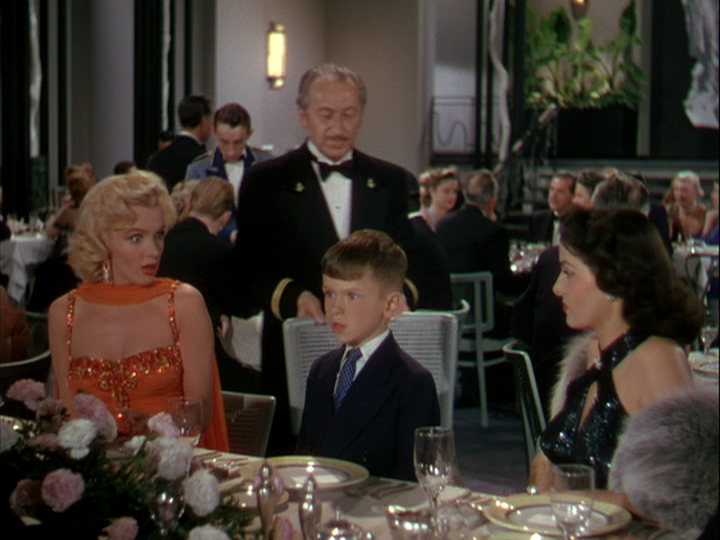

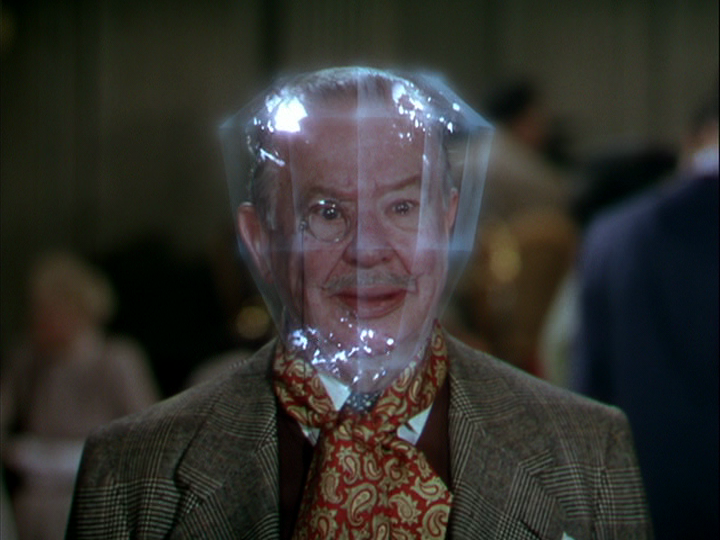

Despite the apparent equality established in the plot and the division of musical numbers, Dorothy plays second fiddle to Lorelei whenever money is around, which is most of the time. On ship, for instance, we’re introduced to another pair of male spectator surrogates, both wealthy and smitten with Lorelei: Piggy (Charles Coburn), a childish septuagenarian, and Henry Spofford III (George Winslow), a mature toddler. Monroe and both actors are refugees from Hawks’s 1952 Monkey Business, a dark comedy about aging, and their roles here represent elaborations of their former cartoon-like characters. Piggy is even rendered via Lorelei’s vision as a literal cartoon diamond — an image of sparkling, ageless stone superimposed over his ancient hogshead countenance.

While Dorothy falls for Malone, Lorelei gets Piggy to give her a diamond tiara belonging to his wife (the snooty Lady Beekman, the film’s only villain). Their worlds collide when Malone takes a snapshot of Piggy embracing Lorelei and Dorothy discovers that he’s a detective. This leads to the farcical retrieval of his film by both women, which occasions the line quoted above and ends with Malone stripped of his jacket and trousers and dispatched in a pink bathrobe . . . After a shopping spree in Paris, Dorothy and Lorelei are confronted by Malone, Lady Beekman, and a lawyer demanding the tiara back. Lorelei refuses, insisting it was a gift, and Malone alienates Dorothy further by getting Gus’s father to cancel the letter of credit.

The movie’s least effective, most conventional number comes when the heroines find themselves penniless in a Paris café. For once Dorothy, who starts the number, takes the upper hand in asserting its meaning, which is essentially social rather than narcissistic, with a crowd of working-class Parisians making up their sympathetic audience. Lorelei’s problem with Gus hasn’t yet been focused by his presence, so in effect her role in the song has more to do with her sympathy for Dorothy’s romantic plight. Lorelei dominates only when there’s money to be had: here there is none, so she briefly assumes Dorothy’s populist identity — dilutes her sexuality with community values and uncharacteristically becomes “one of the people”.

***

Until now, the look of the spectator has been that of someone lying prone and buried, walled up in the darkness and receiving cinematic nourishment rather in the way that a patient is fed intravenously. Here . . . I am on an enormous balcony, I move effortlessly within the field’s range, I freely pick out what interests me, in a word, I begin to be surrounded . . . — Roland Barthes, “On CinemaScope,” 1954

Considering Barthes’s quasi-Bazinian response to CinemaScope as a cinema of choice, the frequent misremembering of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes as anamorphic suggests an unconscious perception of a movie whose “binocular vision” (Barthes’s phrase in the article quoted) proposes two separate points of entry at almost every stage. Seen through Dorothy’s lens, it is a world of warmth and good fellowship; from Lorelei’s angle, it is a world of cold objects to be possessed. Superimposing both angles, Hawks creates a confusing yet reassuring panorama in which men who are cold fish desire to be possessed as warm objects, and women are friendly, narcissistic predators who bring this about. If we try to determine which woman is smarter, the film offers only contradictory signals. Lorelei spouts malapropisms and steals the tiara thoughtlessly, but is a brilliant strategist; Dorothy seems practical, but falls for a faceless lunk with no prospects and unconcernedly defends an amoral thief.

Barthes saw CinemaScope as the vehicle for an “ideal Potemkin, where you could finally join hands with the insurgents, share the same light, and experience the tragic [Odessa] steps in their fullest force . . . The balcony of History is ready.” In contrast to this, he bemoaned the Mythology of The Robe, neglecting to note any incompatibility between one’s ability to scan the latter and the rapid montage making Potemkin possible. Insofar as the “stretched-out frontality” of Monroe and Russell is seen only from the balcony of Mythology, the binocular vision of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is no less incomplete. Add dialectics, class struggle, and the politics of spectacle as assault — three of the linchpins of Potemkin — and the picture becomes fuller, more worthy of being seen from the balcony of History as well: a 1950s debate on the virtues of hoarding versus sharing. The film honors both, but there’s no question which it finds sexier — unless the sharing is strictly between Lorelei and Dorothy, as in the first and last shots.

***

Fifth Number (and Reprise): “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend”

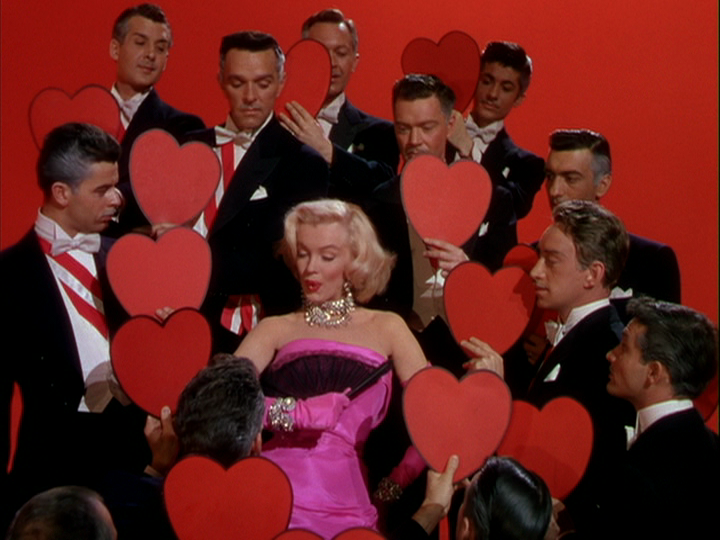

The movie offers two climaxes, on a stage and in a courtroom, with a version of the song performed by each heroine. Both exhibit Hawks’s unsentimental fascination with excess, visible elsewhere in his handling of violence (Scarface), death (The Big Sleep, Land of the Pharaohs), youth and age (Monkey Business), as well as in the first and third numbers here. Lorelei’s version is the better remembered, for it voices her ultimate dark statement in the most opulent manner possible; it is also Monroe’s best-known number. Framed by two encounters with Gus, and intercut with three shots of him at his cabaret table, it comprises as much of a personal affront to him as “Bye Bye Baby”; although this time, at least, it represents an honest one.

Green curtains part to reveal a flaming orange-red set (recalling the costumes in “Little Rock”), dominated by a chandelier bearing bound, smiling women posed as statues holding candelabra; around them waltz couples in formal dress. Lorelei, initially unnoticed in her pink evening dress, arrives at screen center, dripping with diamonds, and repeats “No” in a mock aria to a group of men clutching valentine hearts the same color as the decor, snapping at them in turn with a black fan.

The sequence exults in grating contradictions. Lorelei is indirectly dismissing Dorothy along with men, by putting diamonds first, and her main preoccupation is with the ravages of age: “Men grow cold as girls grow old, and we all lose our charms in the end . . . ” In another chorus, she implicitly extols adultery, in sisterly fashion, to a group of women in pink around her — interjecting “but get that ice or else no dice,” which shatters the hint of Dorothy’s communal influence. The dehumanized world that surrounds her is indeed the world of her glamorous imagination, gaudy but petrified, with a grim, deathly profile of pained acquiescence.

In her last chorus, Lorelei snatches one of the diamond straps that the corpselike gentlemen on stage are dutifully dangling and tosses it to Gus at his table — rejecting and demanding diamonds in the same defiant gesture. Gus downs a drink, doesn’t applaud the number, and when he appears backstage again he’s ready to end their engagement. But to round off the reversal, Dorothy has by now persuaded Lorelei to go to work on Gus to extract the $15,000 needed to replace the missing tiara (which has mysteriously vanished), and Lorelei has already confessed, “I really do love Gus . . . there’s not another millionaire in the world with such a gentle disposition.” An expert calculator, Lorelei estimates that getting the money from Gus will take an hour and forty-five minutes, and while she ushers him in with “Daddy,” Dorothy goes off with gendarmes to impersonate Lorelei in court.

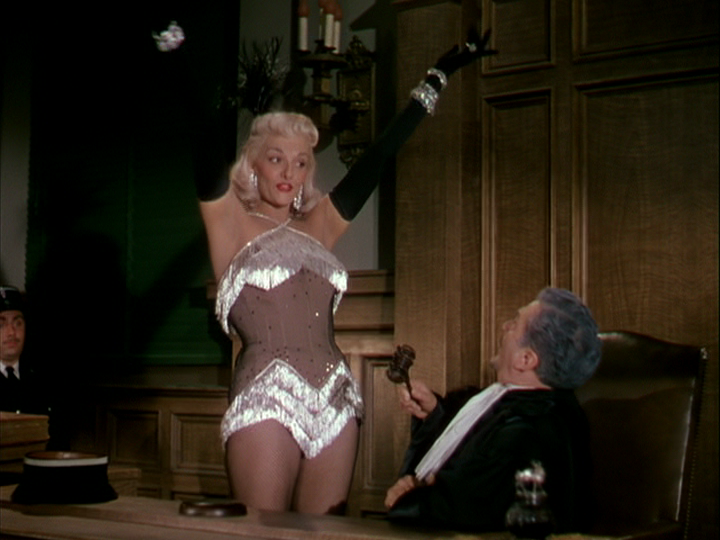

She enters in ermines, flashes some leg to borrow time, and finally breaks into an impromptu “Diamonds” — stripping off her furs to reveal her flashy showgirl outfit and proceeding through a burlesque parody of Lorelei that’s every bit as devastating as Lorelei’s earlier self-parody. The men in the courtroom quickly change into a leering, clapping audience as she plays to each of them in turn, until the judge (Marcel Dalio) finally succeeds in restoring order. By that time, the vulgarity of her bump-and-grind and the reactions to it have tarnished Lorelei’s appeal as decisively as Dorothy’s expediency has compromised her own. In one fell swoop, Dorothy’s social gift becomes demagoguery through Lorelei’s influence, and justice promptly collapses.

The best and worst of both characters have played themselves out. All that remains is the return of the tiara (which Malone traces back to Piggy, after he quits his job to win back Dorothy) and Lorelei’s conquest of Gus’s father (Taylor Holmes, a wizened geezer out of Preston Sturges). Both scenes reduce the plot to a charade by giving us “logical” steps that lead in a perfect circle. The tiara gets ceremoniously passed from Piggy to Malone to Dorothy-as-Lorelei to judge to lawyer and back to Piggy again; and Lorelei uses the same technique on Gus’s father that she has already practiced on Gus himself — while the question of how brainy she actually is gets passed through a few more contradictory, jokey exchanges.

***

Final Reprises: “Little Rock” and “Diamonds”

Remember, honey, on your wedding day, it’s all right to say yes. — Dorothy to Lorelei

Dressed in virginal white and carrying matching bouquets, Lorelei and Dorothy sing “Little Rock” with a revised conclusion as they grandly march down steps and the aisle to their grooms. While the camera pans from (1) Dorothy looking from her diamond ring to Malone to (2) Lorelei looking from her diamond ring to Gus and (3) back to Dorothy and Lorelei together, looking at us, a heavenly mixed chorus offscreen reminds us that “Square-cut or pear-shape, these rocks don’t lose their shape” — implying that the disparate demands of humanism and capitalism, community and narcissism, can be finally met when the perfect circle becomes a wedding ring. But the last sly look of glancing complicity between Dorothy and Lorelei suggests that they have collectively sold us a bill of goods, an impossible object — a CinemaScope of the mind, a capitalist Potemkin.

— Sight and Sound, Winter 1984/1985