From Sight and Sound (Winter 1974-75). — J.R.

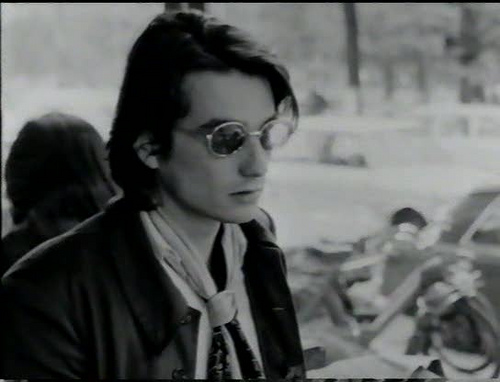

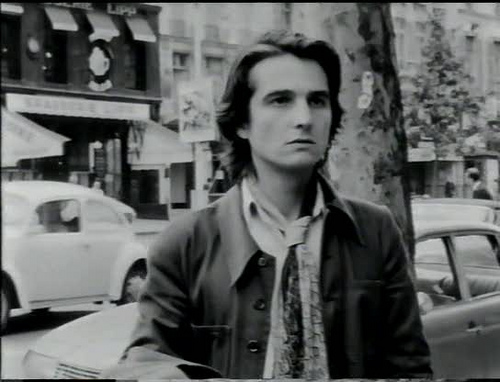

“The day I stop suffering, I’ll have become someone else.” “There’s no such thing as chance.” “To speak with the words of others — that’s what I’d like. That’s what freedom must be.” From the Café aux Deux Magots to the adjacent Flore, from the streets and sidewalks of a grayish Paris to other people’s flats, for the better part of 219 minutes, Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) continues to hold forth. “In May ’68 a whole café was crying. It was beautiful. A tear-gas bomb had exploded . . . a crack in reality opened up.” Charmingly, narcissistically, elaborately, endlessly: “I don’t do anything; I let time do it.” “Abortionists are the new Robin Hoods . . .the scalpel replaces the sword.” “The world will be saved by children, soldiers” (pregnant pause) “and fools.”

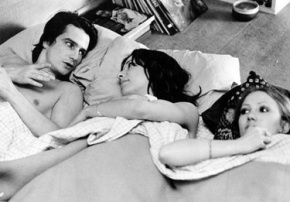

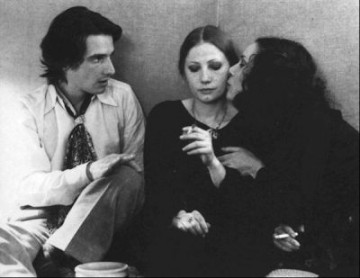

Much less talkative is his beloved Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten—a Bresson discovery back for another nonperformance), who forsakes him to get married, and Marie (Bernadette Lafont), the older woman he lives with, casually exploits, and is clothed and fed by. But a verbal match of sorts is offered by the doleful and doelike Veronika (Françoise Lebrun, in an extraordinary, glowing debut), a promiscuous nurse he picks up one afternoon. Next to Alexandre’s, her words come across as blunt and unvarnished. “I can fuck anyone.” “Watch out — you’ll push in my Tampax.” “I’ve screwed a maximum of Arabs and Jews.” While serving Nescafé: “I like the feel of a prick against my ass even if it’s soft. One sugar or two?” And in a long drunken soliloquy tainted with death and despair, tears and mascara streaking down her cheeks: “There are no whores. . . . Love is nothing if you don’t want a baby together.”

Central to the feel and method of Jean Eustache’s THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE is its obsessive confessional tone, much closer to Pialat than to Rohmer; its slavish fidelity — apart from some time abridgements — to repetitious verisimilitude; its sense of private ghosts being desperately laid to rest. (The ghostly fades between sequences conjure up spectral memories of Murnau as much as the beautiful scene at the Gare de Lyon restaurant, where Alexandre compares the setting to a Murnau film, a locus of transitions.)

In barest outline, boy meets whore, courts her — a crucial shift of operations from Deux Magots to Flore, with each successive date set at an earlier hour —a nd eventually beds her in Marie’s flat while the latter is away in London. Marie returns, he introduces Veronika, and abortive attempts at a three-way sleeping arrangement culminate in Marie’s attempted suicide, Alexandre’s reduction to self-loathing and manic helplessness (retreating to the bathroom in the midst of an emotional crisis to spray himself with cologne), and Veronika’s convulsive lament for the emptiness of her many sexual exploits. She insists on going home and Alexandre accompanies her, listens to more drunken abuse (“You disgust me. I may be pregnant by you. I love you”), leaves, and then hurries back to propose marriage. She accepts, vomits offscreen into a basin, and we end with the camera fixed on Léaud, stunned and slumped on the floor against her refrigerator. It is less a resolution of conflict than a depletion — an exhaustion of the will that seems (like the characters) more prone to regurgitate sickness than reflect on it.

Yet obstinately and paradoxically, this monumental epic of psychic imprisonment sticks in one’s craw. Refusing to see beyond the characters and their limitations, the film repeatedly pushes us back into their snarled and messy lives. Encased in the retrospective black-and- white ambience of Nouvelle Vague — when Léaud was Antoine Doinel, or MASCULIN-FÉMININ’s Paul, or the provincial hero of Eustache’s earlier LE PÈRE NOËL A LES YEUX BLEUS — the film turns these youthful dreams into bitter ashes. Formally the antithesis of Rivette’s OUT 1 in its exclusively written dialogue and old-fashioned narrative linkage, it carries a bleak mood that is equally redolent of post-1968 disillusionment, and similarly suggestive of vicious concentric circles.

Over the plot’s relentlessly even progression, Alexandre’s nonstop aphorisms cumulatively take on the appearance of habitual camouflaging gestures. (Eustache wrote the part expressly for Léaud, and it is clearly a character that both of them understand down to their bones.) And the mounting impact of Veronika’s obscenity and sarcasm — evaluating her body parts like a used car salesman — ultimately turns, for all its leveling effect, into another kind of cant and cliché, offering no promise of release.

Static medium shots of people talking: a zero point of cinematic style, perhaps, but Eustache holds to it with such precision that the slightest pan — Veronika’s reproachful greeting of Alexandre defining a quick trajectory across a room — carries an unusual weight. Elsewhere, it defines a neutral surface on which faces, voices, and words (the latter two rendered in direct sound) are made to register as epiphanies, regardless of what they say or do.

“The film begins in the first person,” Eustache has noted, “in order to end in several first persons.” Specifically, a strict adherence to the hero’s field of vision is veered from only twice. The last time we see Marie, after the others’ departure, she is listening to a scratchy Edith Piaf record — the static camera recording her own virtual stasis for the song’s duration. As much of a climax as the tirade by Veronika that immediately precedes it, this shot similarly composes a definitive “still-life,” with the ironic lilt of Piaf’s song (“Les Amants de Paris”) serving as a mock epitaph. Soon afterward, we glimpse Veronika changing into her bathrobe before Alexandre enters her room to propose — a more academic and less striking demonstration of the same principle, that Alexandre’s glib overview and control of events has been irrevocably broken.

And what has replaced it? Taking apart a social-ethical system to show us its bleeding entrails, Eustache makes no effort to sew it up again. The female roles indicated in the film’s title have been invested with enough ambiguity to suggest a reversal — Veronika becoming the expectant mother, Marie the abandoned whore — but not enough to suggest that any alternative roles might exist. Freedom collapses — helped along by a few shallow cracks Alexandre makes about Sartre, sitting at a nearby café table — and life reverts to Catholic bourgeois “necessity,” which is implicitly treated as biological truth. Nouvelle Vague dies an ignominious death, and the spirits (if not the minds) of Claudes Berri, Sautet, and Lelouch lurch to the fore.

Perhaps this is overstating the case; but as a view of cinema as well as a view of life, LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN seems to me profoundly reactionary. This is already hinted at in the jokey treatment of Alexandre’s idle friend, whose cluttered room with stolen wheelchair and Nazi memorabilia suggests a fascist playpen; or in the nostalgic use throughout of old records, reflections of yearnings for the presumed certainties and absolutes of the past. And yet, like Long Day’s Journey Into Night, like the better parts of ICE or FACES, the film’s compulsive picking at wounds reveals a genuine impasse, a tragic lack in ourselves that cinema seldom admits, much less describes — a cry of animal defeat lending Eustache’s essentially destructive masterpiece a scarred authenticity that sears the mind and persistently haunts the emotions.

— Sight and Sound, Winter 1974–1975