Posted in Moving Image Source on November 13, 2009. — J.R.

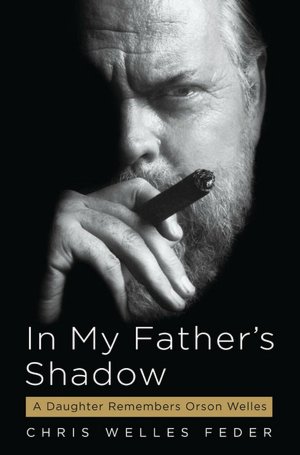

“The book you are about to read is not another biography of Orson Welles,” begins Chris Welles Feder’s In My Father’s Shadow: A Daughter Remembers Orson Welles (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill). “It owes nothing to scholarly research and everything to firsthand knowledge.” Because this story by Welles’s oldest daughter is about neglect and absence as well as about love and presence, one feels from the outset that her very moving cri de coeur was written out of psychic necessity rather than out of any academic or commercial impulse — a passionate and even somewhat desperate attempt to lay certain ghosts to rest. And part of this book’s uncommon strength is that it ends on a positive note with a lot of hard-won wisdom, in spite of all the grief it recounts.

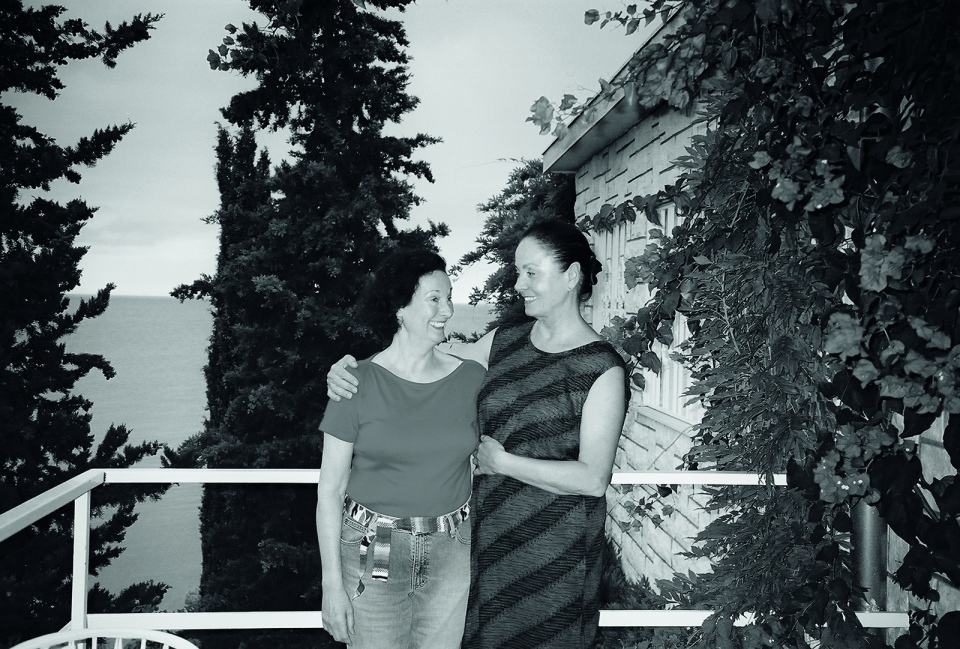

Orson Welles married three times and had a daughter from each marriage, although the woman who mattered the most in his life, at least during the last two decades, was none of these half-dozen women but Oja Kodar, his mistress and collaborator (mainly as actress and/or co-writer — on F for Fake, the unreleased The Other Side of the Wind, and many other unfinished or unrealized projects, such as The Dreamers). Arguably, I think one can only begin to understand Kodar’s role in several Welles works and projects once one realizes that he didn’t merely want to show off her beauty; he also deeply identified with her, even as an exhibitionist. Consequently, making her the center of attention sometimes enabled him to reflect on himself more indirectly. This becomes clearest, perhaps, in The Dreamers, the most treasured of Welles’s late projects and scripts, portions of which were shot, based on two Isak Dinesen stories, in which Kodar plays Pellegrina, an opera singer who decides, after losing her voice, to assume many successive identities and lead many separate lives.

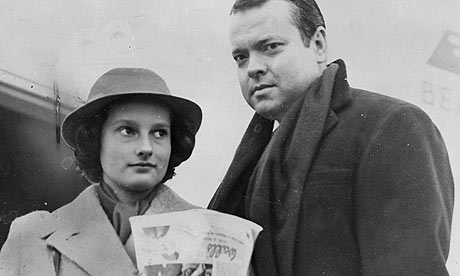

The wives, by contrast, were only fitful collaborators at best: Virginia Nicolson, married in 1934, appears in Welles’s silent short Hearts of Age (filmed as a prank) and in some stage and radio works; Rita Hayworth (1918-1987), married in 1943, joined him on a few radio spots and (more briefly) in The Mercury Wonder Show but mainly in the title role of The Lady From Shanghai; Paola Mori (1930-1986), married in 1955, played the female lead in Mr. Arkadin. And the daughters figure in his work even less: Christopher, born 1938, in a cameo in Macbeth (1948); Rebecca (1944-2004) not at all; and Beatrice, born 1955, in a cameo in Chimes at Midnight.

We also learn from Christopher that when she begged at age eight to appear in The Lady From Shanghai, during the Acapulco shoot, her father grudgingly cast her as “an American brat eating an ice cream cone.” She records her disappointment years later in not making the final cut. But she may not realize that a bratty American girl with a similar line of dialogue did make it into the film’s January 1947 cutting continuity, as reported in James Naremore’s expanded 1989 edition of The Magic World of Orson Welles.

Truthfully, I respond to her book far more on a personal level of identification than as a Welles scholar — even though there are plenty of reasons for us Welles scholars to be interested as well. (Just for starters, her grim and devastating account of her father’s funeral in her prologue is indispensable.) To grow up with a parent who often isn’t around, emotionally as well as physically, is far more difficult when the feeling of rejection is intermittent and inconsistent rather than constant, and this is an experience I knew firsthand, with my own mother. If one expects nothing, adjustment is much easier, but when the love comes and goes in unpredictable torrents and waves, it can only be maddening. And this is the conundrum Christopher Welles has been wrestling with her entire life.

In fact, this book qualifies as her second effort to negotiate her difficult legacy. Her first — a collection of 75 fictional poems entitled The Movie Director, published privately in a limited edition in 2002 — deals with the same issues, characters, and emotions, but in the form of imaginary monologues. Here, for instance, is ” King Lear’s Daughters”:

One night you claimed us on television,

announcing to the world that like King Lear

you had three daughters, but unlike him,

all your daughters had been kind to you.

Eager to move on, you beamed at the audience,

tugged at your beard, the Grand Old Man playing

Santa Claus, Lear and Houdini all at once.

In place of yourself, you had offered an act of magic:

First we all become Cordelia. Then we all disappear.

In her memoir, the TV interview proves to be Dick Cavett’s, where Welles characterizes the eldest as “frighteningly bright” and a writer living in New York, Rebecca as a “flower child,” and Beatrice as a “horse woman.” And Christopher reflects:

The phrase lodged in my mind: frighteningly bright. Did my intelligence scare my father away? Would he feel closer to me if I were not as bright? I could speculate endlessly and arrive at no satisfactory answer. I could also spend the rest of my life wondering why, when my father was alone with me, he could not be as relaxed and natural, as seemingly “himself,” as he was on talk shows. Could it be that the “real” Orson Welles was not the father I met in hotel rooms but the one I saw on television?

And the anomalies started even before she was born, with her name, which her father proudly selected. When she asked him why he came up with a boy’s name, causing her to be teased by kids at school, he would cite only her uniqueness, which prompted him to send out scores of telegrams when she was born, announcing, “CHRISTOPHER SHE IS HERE” — not one of which she ever saw.

The surrogate parents she remembers with special warmth include “Chubby” Sherman (a onetime stage actor in Welles’s Mercury Theatre); screenwriter Charles Lederer, her first stepfather (whose status as Marion Davies’s nephew enabled her to visit William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon as a tot); Rita Hayworth; and Hortense Hill, wife of her father’s teacher and headmaster, Roger Hill, at the Todd School for Boys (which she also attended, as a unique girl student, for a spell). Given that her mother’s third marriage (to an English war hero) when she was 11 led to moves to Rome (when her father also was living there), then Johannesburg, and finally to Lausanne (where she was sent to a “finishing school,” over her own protests), and that her first marriage also occasioned a move to Seoul, her life has been in many ways as peripatetic as her father’s. Or at least it was until she met her second husband, Irwin Feder, and settled with him into a career of educational writing and publishing (including an extended stint at Encyclopedia Britannica), mainly in New York, for over four decades.

Perhaps not surprisingly, it appears that she fell into her father’s orbit far more often when her life (as well as his) was more unstable. So it probably shouldn’t be so surprising that she didn’t even see Citizen Kane until her late teens, in Chicago, when she found the film so overwhelming that it introduced her to the very possibility of film as an art form, and she wound up seeing it several times. But no less surprising, if heartbreaking, is the fact that by the time she belatedly had a chance to blurt this out to her father, at a reunion in Hong Kong years later, he could only respond by saying, “Citizen Kane! Good Christ, that’s all I ever hear about. You’d think I’d never done anything else in my life.” (“My worst fear,” she notes soon afterward, “was being ‘a bourgeois vegetable’ in his eyes.”)

Like the time he pressured her when she was still in the third grade into ordering oysters at the Brown Derby, this probably shows her father at his least empathetic, unless one also counts all his recurring absences. He failed to attend either of Christopher’s weddings, and I was mortified to discover that the career summary in This Is Orson Welles, which I edited, claims that he flew to Chicago for the first of these. (This may have been an error I simply inherited, yet it’s emblematic of a life that she aptly suggests has been lived in shadow, in which misunderstandings and confusions of this kind seem inevitable.) But there are other points recounted in this book, especially during her teens in Europe, when he sounds like the best father any girl might have had; the guided tours she describes (while he was shooting Mr. Arkadin) of Goya etchings in the Prado and El Greco’s The Burial of Count Orgaz in a Toledo church are particularly memorable.

But my favorite parts of this book are the last two chapters, most of which are devoted to the mammoth Welles retrospective and conference organized by Stefan Drössler in Locarno in 2005 and Feder and her husband’s visit to Kodar at the magnificent Villa Welles on the Dalmatian coast of Croatia the following month. Having met her and Irwin in Locarno and visited Kodar at Villa Welles myself, two summers later, I can testify to the vivid accuracy of both accounts. (I personally regard the Villa Welles as Kodar’s greatest work of sculpture.) I’m particularly grateful for the portrait of Kodar, offering a bracing alternative to the resentful treatments from so many others (most of whom know her slightly or not at all) who have irrationally blamed her for having somehow taken Welles away from them. As Feder aptly puts it, “My father’s life was his work, and of all the women who attempted to live with him, only Oja was capable of entering fully into his creative life.”