From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 512). — J.R.

Buffalo Bill and the lndians, or

Sitting Bull’s History Lesson

U.S.A., 1976

Director : Robert Altman

Cert-A. dist-EMI. p.c–Dino De Laurentiis Corporation/Lion’s Gate Films/Talent Associates-Norton Simon. exec..-p-David Susskind. p– Robert Aitman. assoc. p–Robert Eggenweiler, Scott Bushnell, Jac Cashin. p. exec—Tommy Thompson. asst. d–Tommy Thompson,Rob Lockwood. sc–Alan Rudolph, Robert Altman. Suggested by the play Indians by Arthur Kopit. ph–Paul Lohmann. Panavision. col–Deluxe General.ed-Peter Appleton, Dennis Hill. p. designer–Tony Masters. a.d–Jack Maxsted. set dec–Dennis J. Parrish, Graham Sumner. scenic artist–Rusty Cox. sp. effects–Joe Zomar, Logan Frazee, Bill Zomar, Terry Frazee, John Thomas. M–Richard Baskin. cost–Anthony Powell. make-up–Monty Westmore. titles-Dan Perri. sd. ed–William Sawyer,_Richard Oswald. sd. rec–Jim Webb, Chris McLaughlin. sd. re-rec–Richard Portman. research–Maysie Hoy. wrangler–John Scott. l.p–Paul Newman (Buffalo Bill), Joel Grey (Nate Salsbury), Burt Lancaster (Ned Buntline). Kevin McCarthy (Major John Burke), Harvey Keitel (Ed Goodman), Allan Nicholls (Printiss Ingraham), Geraldine Chaplin (Annie Oakley). John Considine (Frank Butler), Robert Doqui (Osborne Dart), Mike Kaplan (Jules Keen), Bert Remsen (Crutch), Bonnie Leaders (Margaret), Noelle Rogers (Lucille Du Charmes), Evelyn Lear (Nina Cavalini), Denver Pyle (McLaughlin),Frank Kaquitts (Sitting Bull), Will Sampson (William Halsey), Ken Krossa (Johnny Baker), Fred N. Larsen (Buck Taylor), Jerri Duce and Joy Duce (Trick Riders), Alex Green and Gary MacKenzie (Mexican Whip and Fast Draw Act), Humphrey Gratz (Old Soldier), Pat McCormick (Grover Cleveland), Shelley Duvall (Frances Folsom). 11,105 ft. 123 mins.

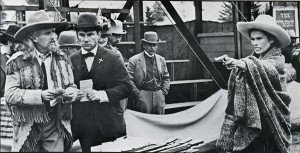

1885. At his Wild West Show, Buffalo Bill Cody is informed of the arrival of Ned Buntline, the popular writer who helped to create his legend; he asks his partner Nate Salsbury to get rid of Buntline, and turns his attention to the arrival of Sitting Bull, a political prisoner brought by Indian agent McLaughlin to appear in the show.

Remaining mute, Bull is represented by Indian William Halsey, who immediately demands that their entourage live across the river and that Bull be paid six weeks’ salary in advance and be given blankets for all the members of his tribe, adding that Bull has agreed to come only because he has dreamt that he would meet the President there. But after a further demand is made that the show’s re-enactment of Custer’s Last Stand be replaced by a more truthful account of another event — showing that after the Sioux embraced the soldiers, the latter slaughtered every Indian in the village — Cody fires Bull, and hires him back only after his sharp-shooter Annie Oakley threatens to leave in protest. Bull’s act in the show finally consists of riding around the arena, which initially elicits jeers from the audience but ultimately wins them over.

Learning that Bull has left, Cody rides off after him, only to return empty-handed and humiliated to find that Bull has returned of his own accord. A wire arrives from President Grover Cleveland who plans to stop over with his wife Frances Folsom on their honeymoon to see the show. Appearing uninvited at the reception afterwards, Sitting Bull tries to make a request to Cleveland but is denied a hearing. Afterwards, Cody has a drink with Buntline, who agrees to leave. Bull disappears, and Cody later hears that he has been shot dead at Standing Rock. Waking up one night, he carries on an imaginary conversation with Bull, trying to justify himself. His Wild West Show proceeds to re-enact ‘history’ with Halsey representing Bull in a staged combat with Buffalo Bill, who defeats him without difficulty.

With a career that has already zigzagged from the brutally confident machinations of M*A*S*H to the sensitive suspensions of McCabe and Mrs. Miller, from the congealed arthouse clichés of Images to the exhilarating improvisations of The Long Goodbye and California Split, one has come to expect the unexpected from Robert Altman, acknowledging the unpopular but inescapable fact that consistent formal development is virtually impossible today within the dictates of commercial American cinema. Hardly surprising, then, that the most serious claims made for Hollywood and post-Hollywood directors refer to ‘development’ principally on a thematic level, and that Nashville was characteristically praised less for its ambitious formal design than for the thematic complacencies which circumscribed and eventually overran it.

Specifically, the American flag bandied about at the end of that film — which shrank the open-endedness of two dozen mini-plots to the level of a platitude — was regarded instead as a kind of expansion, because thematically it ‘meant something’. And if Buffalo Bill and the Indians uses that same flag repeatedly from first shot to last as a sign of its own ‘serious’ credentials, it is hardly coincidental that the film also ‘means something’ with a consistency and monotony that is unparalleled in Altman’s work. That the film’s theme is irrefutable surely deserves recognition: the genocide perpetrated by whites on the American Indian is a matter of historical record, and the systematic distortion of this fact by popular American media is no less evident. Considered purely as agit-prop — neatly timed for a 4th of July American release at the start of this bicentennial summer — Buffalo Bill and the Indians might seem justifiable as an instrument for ramming this point home if it went about its business with some historical rigour.

Unfortunately, Altman appears to know a lot more about show business than about the American Indian, and what he knows about the former mainly consists of behavioural observation; by scaling this observation down exclusively to what illustrates his thesis — the hollow fakery of Buffalo Bill and his followers — he thus allows himself precious little to work with, thematically or otherwise. Within five minutes, everything he has to say on the subject is apparent; by the time Cody’s nephew Ed (Harvey Keitel) is muttering, “I tell you, there ain’t no business like the show business” — still quite early in the proceedings — a fatal note of redundancy has already set in. The standard repertoire of Altman gags (e.g., the succession of opera singers Cody takes on as mistresses; his callow racist slurs; his multiple ineptitudes; the obligatory out-of-synch singing of the “Star Spangled Banner”, from Brewster McCloud) is consequently allowed little opportunity for surprise or development, and with grinding regularity, everything that Cody does or says is pathetic while everything communicated by Sitting Bull is noble and dignified. This largely leads (in part, thanks to Paul Newman’s touching performance) to Cody becoming the principal centre of sympathy and attention, as a kind of surrogate for the liberal guilt of the white spectator. In keeping with this pattern, the penultimate sequence, during which a drunken Cody delivers angry slogans to an emblem of the dead Indian chief (“God meant for me to be white — and it ain’t easy !”; “I give ‘em what they expect. You can’t live up to what you expect. And that makes you more make-believe than me, ’cause you don’ even know if you’re bluffin’. . .”), rings with the jaded theatricality of an Arthur Miller, and it is significant that Altman himself has compared his hero to Death of a Salesman’s Willy Loman. Given such a lugubrious context, it should be stressed that Altman’s actors acquit themselves admirably within the relatively tight constrictions of their assigned roles: Will Sampson is as imposing here as he was in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, while Burt Lancaster lends considerable charisma to his marginal but crucial role as myth-maker. Geraldine Chaplin, less inventive here than in Nashville, still brings a sense of dignity to her essentially sentimental part as Annie Oakley, and in the film’s best scene manages to convey some of the strain and effort that her real-life character‘s act must have demanded. A pointed contrast to the film’s continual emphasis on humbug elsewhere, it suggests -– however briefly — what a less simple-minded debunking of the Buffalo Bill myth might have involved. Any sign of Altman’s formal interest, however, will have to wait for another project.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM