From Sight and Sound (Winter 1973/4). For a subsequent production story about this film written for Film Comment, devoted mainly to a day of studio shooting, go here. –- J.R.

Since the beginning of October, Alain Resnais has been shooting Stavisky, his first feature since Je t’aime, je t’aime (1968). ‘When Jorge Semprurn first spoke to me about making a film on Stavisky,’ Resnais said recently, ‘I admitted to him that at the age of twelve, in the Musée Grévin, I stood dreaming before the wax figure of this character, whom I compared to an Arsène Lupin swindling the rich and helping the poor.’

Actually, Serge Alexandre Stavisky (born in Russia as Sacha) was a swindler who sold 40 million francs’ worth of valueless bonds to French workers, but he moved about in high circles. In spite of a shady past, he was generally known in the early 1930s as a respectable financier with first-rate political connections, associated with the municipal pawnshop of Bayonne. When his fraud was discovered in December 1933, he promptly fled, and the police caught up with him in Chamonix the following month. According to official history, he either committed suicide or was murdered by the police, although the latter explanation appears the likelier one: the Paris press rather implausibly reported that he fired two bullets into his head. The revelation of his crime resulted in the downfall of two ministries. The Radical Socialist premier Camille Chautemps was forced to resign after right and left extremists accused him of crooked deals with Stavisky; then his successor Daladier also had to step down after using force to repress the bloody riots staged by extremists (mainly royalists) in February 1934.

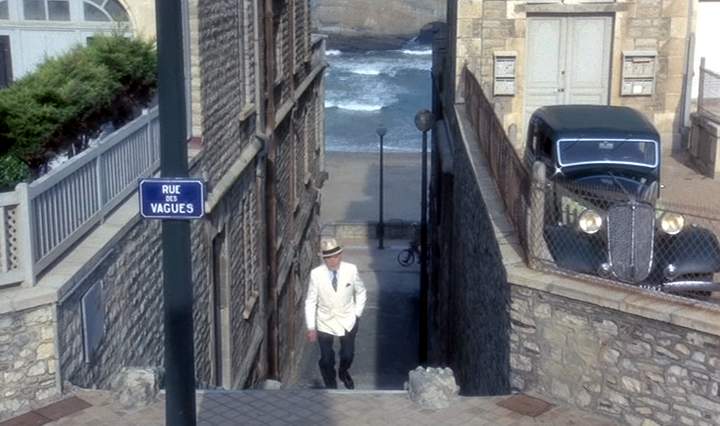

All this plus Jorge Semprun seems to add up to a ‘timely’ political thriller, but Resnais has indicated that he has something a bit different in mind. ‘It’s the legend of Stavisky that we’re going to film: the fiction and even the fantasy taking precedence over the authenticity. I don’t believe in historical films. One hopes, however, to be sensitive to the flavor of a period . . . [I’m not] trying to make an apology for Stavisky, but it appears that the man had charm.’ Or as Semprun puts it, ‘The mood will be more Lubitsch than Losey.’

Or will it be a matter of Minnelli overtaking Trotsky? Stephen Sondheim, who composed the lyrics to West Side Story and Gypsy, and the music and lyrics of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, is supplying Stavisky‘s score. Trotsky (Yves Peneau) figures briefly in the action when Stavisky is introduced to him and his family in Barbizon. He also meets Herna Wolfgang (Sylvia Bodesco), a young woman who facilitates the encounter and whom Stavisky (Jean-Paul Belmondo) promises to give an audition to at the Empire, his theatre in Paris. (The film’s original working title was L’Empire d’Alexandre.)

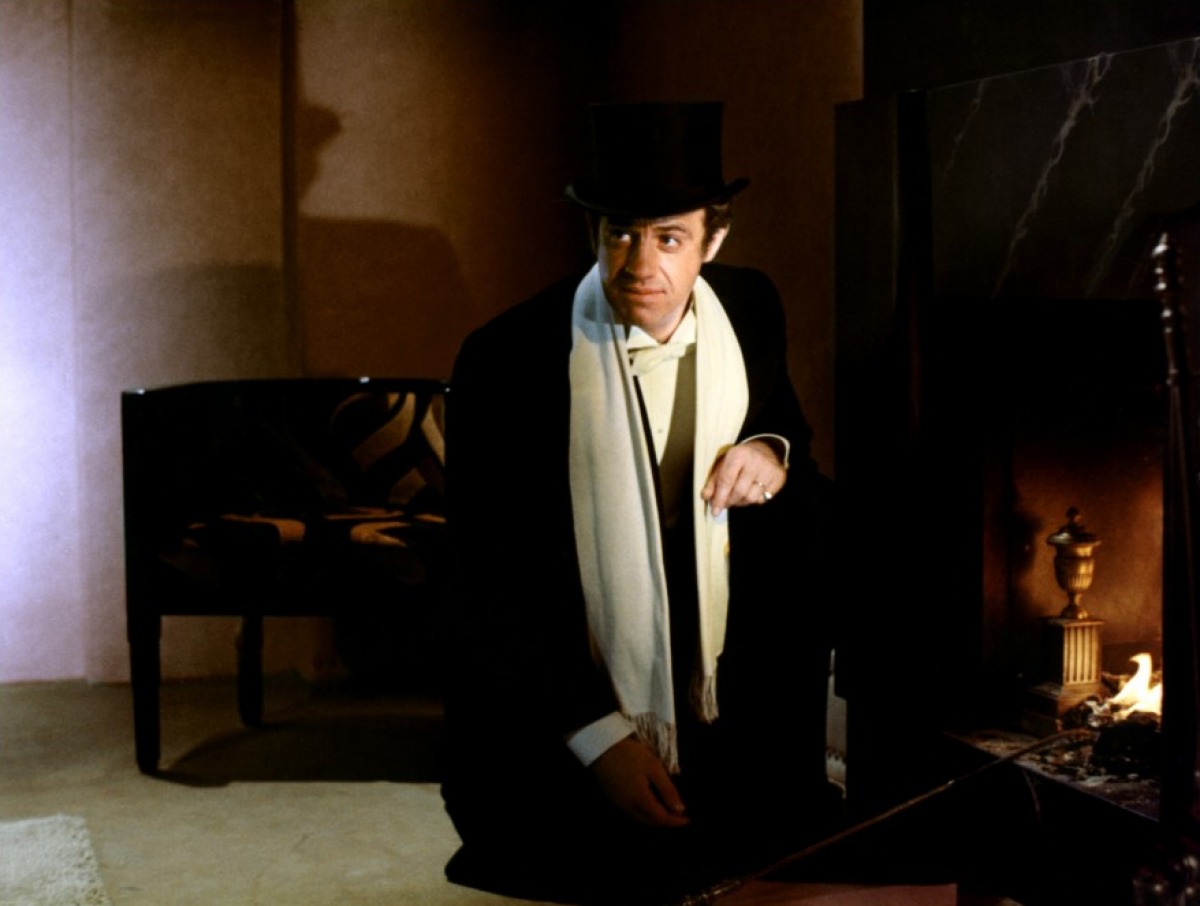

Last November, Resnais and his crew were filming some scenes set in the Empire a few blocks north of the Opéra at Théâtre Mogador, which was concurrently presenting an operetta called Douchka. The brief part of the shooting that I watched was taking place on the stage, where Resnais was unobtrusively ‘conducting’ a rapid tracking shot that moved diagonally across about half of the stage’s length, accompanying Alexandre and Herna while they exchanged a few lines. Behind them was a quaint Russian backdrop, apparently a fixture of Douchka, although one couldn’t tell how sharply the Panavision camera kept this in focus as it sped across the planks. Belmondo — who is essentially financing this French-Italian production by furnishing 80% of the budget – was dressed in a snappy grey-striped suit with a red carnation; Bodesco wore a more modest 1930s frock. The elated mood on the set, visible in members of the cast and crew, appeared to be equally relaxed and controlled, and Resnais’ multiple activities — as he squinted through his viewfinder, checked something in the script, counseled the actors, looked through the camera lens for each set-up, or simply stood watching — were so calmly ubiquitous that they often had the effect of seeming invisible.

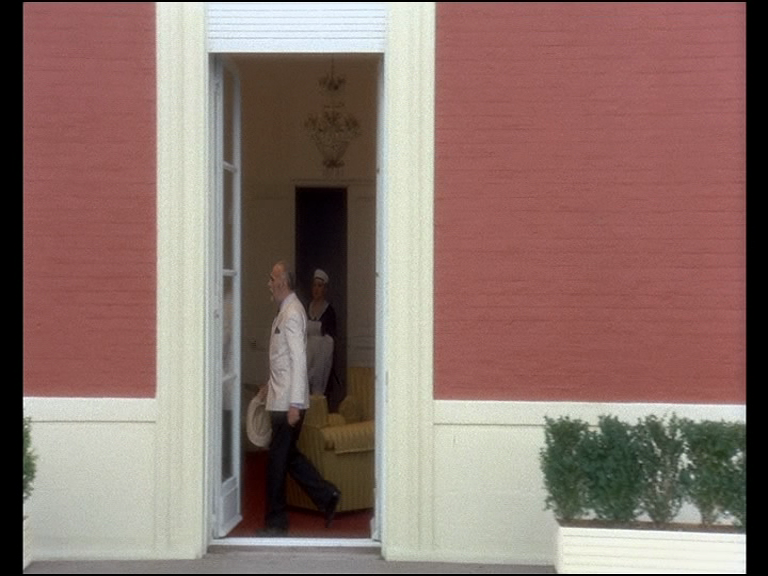

Other members of the cast include Charles Boyer as Baron Raoul, François Périer as Borelli, Anny Duperey as Stavisky’s wife, and Michel Lonsdale and Claude Rich in smaller parts. Having already shot sequences in Biarritz and Barbizon, the crew was planning to continue at a studio outside Paris before concluding at Chamonix in mid-January, roughly one year after Semprun and Resnais began work on the script. The film is expected to run about135 minutes and will be released in the spring, probably in time for the Cannes Festival.

Will the film have an experimental side? ‘Not in its overall structure,’ Semprun tells me when I ring him up. (As is customary with Resnais, the scriptwriter stays away from the shooting.) ‘In Resnais’ treatment of the period, yes, I suspect so. The construction is relatively simple.’ How will the chronology be handled? No flashbacks; one flash-forward to the death of Montalvo (Robert Bisacco), a rich Spanish friend of Stavisky’s; the rest chronological, beginning in July 1933 and ending with Stavisky’s death the following January.

Is it relevant, one wonders, that only five or six months after the latter date, Resnais first encountered ‘Harry Dickson, the American Sherlock Holmes’ at the newspaper kiosk of Vannes railway station? (Cf. Francis Lacassin’s article in the Autumn 1973 Sight and Sound.) Is it possible that some of the ambience of Resnais’ dream proiect may have found its way into l’affaire Stavisky? At some point between the 40th anniversary of Stavisky’s death and the 40th anniversary of Resnais’ childhood discovery, we should have some sort of basis for an answer.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM