From the Chicago Reader (October 27, 2006). — J.R.

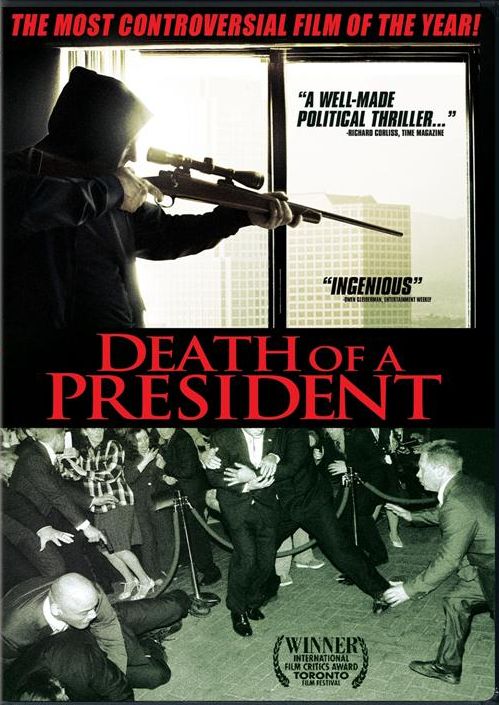

Death of a President **

Directed by Gabriel Range

Written by Simon Finch and Range

With Hend Ayoub, Brian Boland, Patricia Buckley, Jason Abustan, and Chavez Ravine

I dislike few buzzwords more than mockumentary, which even academics now use casually and uncritically. People often assume it’s a neutral descriptive term, but unlike pseudodocumentary — an honest and serviceable label — mockumentary leads many to conclude that the documentary form that’s being imitated is also being made fun of. Most of the works that get labeled mockumentaries are actually honoring the form, by using its techniques to make them seem more real.

According to Wikipedia, the term was first used by Rob Reiner while describing his own This Is Spinal Tap (1984), a popular spoof that led to many successors, including movies directed by Christopher Guest like Best in Show and A Mighty Wind. But these films weren’t so much mocking the documentary form as mocking documentary content. Of course there are films that mock documentary form much more directly, including Peter Watkins’s The Battle of Culloden, Jim McBride’s David Holzman’s Diary, and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane and F for Fake. (Welles also mocked the radio documentary form with his War of the Worlds broadcast.) But the term is being used much too loosely.

Gabriel Range’s pseudodocumentary Death of a President has no trace of mockery, so I’m not sure why so many critics are labeling it a mockumentary. It was controversial even before it premiered at the Toronto film festival, because it purports to describe the aftermath of the assassination of George W. Bush on a visit to Chicago in October 2007. Early infotainment reports gave the impression that the movie assassination was a good thing, a cause for celebration. In fact it ushers in a good many bad things, starting with Cheney becoming president and his Patriot Act III legislation further curtailing civil liberties in the name of security. Moreover, the story is supposed to get the viewer thinking about issues, especially the degree to which anti-Muslim bias inflects American thought.

Death of a President honors the documentary form, which we tend to regard as a form promoting thought and reflection. But it also honors the form of a mystery thriller — and generally speaking, for this form to function properly it has to encourage us to suspend analytical thought about the form of what we’re watching and go with the narrative and emotional flow. As a consequence, Death of a President is trying to go in two directions at once. Like Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville, it’s trying to use the future as a way of getting us to think about the present, encouraging critical reflection. But like any ordinary mystery, it also wants us to be carried along rather mindlessly, without thinking too much about the ways we’re getting information.

The film’s main novelty is its mix of stock news footage (slightly doctored) and fictional interviews that create a believable dystopian scenario. There’s no obvious political slant. No one’s truly a hero or villain in the rush of events: angry anti-Bush demonstrators, cops, FBI agents, and one of Bush’s speechwriters are all shown with equal detachment. B. Ruby Rich argues in the Guardian that an important part of the film’s agenda “is to demonstrate how efficiently technology can be used to misinform.” But Death of a President is actually inviting us to be swept along by the news format, trusting the interviewees as much as those we normally see on TV news shows.

Postmodernist skepticism maintains that everything we see on TV is a bit of a sham. As John Powers recently wrote in the Nation, “Media politics today is all about repeating the same few things until they seem inevitable, even if — especially if — they’re not true.” Yet the reality is that we tend to believe some kinds of TV sham, even if we reject others.

Death of a President compulsively repeats, without mocking, the sort of news-format tropes — especially those involving interviewees speaking to the camera — that we constantly encounter on TV and in documentaries and pseudodocumentaries. Even knowing that the film’s interviews are fake doesn’t prevent their format from seeming inevitable and therefore natural, even real after a fashion.

The English-born Peter Watkins, who qualifies as the inventor and master of the pseudodocumentary as it’s made today, is in some ways the most interesting theorist on the form. (He’s shamefully neglected, even though most of his major works are now available on DVD.) His first two major films using the form were The Battle of Culloden (1964), about a battle fought in Scotland in 1746, and The War Game (1965), an SF film about the near future — to which Death of a President is deeply indebted.

On his Web site Watkins describes his two films this way: “In the first, I employed the style used in Vietnam War newsbroadcasts in order to bring a sense of familiarity to scenes from an 18th century battle, in the hope that this anachronism would also function to subvert the authority of the very genre I was using.

“The second film was the first of my works to deliberately mix opposing cinematic forms (in this case, a series of static, high-key lit, recreated interviews with establishment figures, colliding with jerky scenes of a simulated nuclear attack). Which — if either — was ‘reality’? — the fake interviews in which people quoted actual statements made by existing public figures, or the newsreel-like scenes of a war which had never taken place?”

Despite the sarcasm and scorn heaped on the officers of Culloden by the narration and intertitles and the strange effect of using contemporary documentary methods on an 18th-century subject, the film isn’t mocking the documentary form. Neither is The War Game. Like Death of a President, it’s far too frightening and compelling as a vision of something that could actually happen to be anything but a pseudodocumentary that serves up its form and content straight.

Still, Death of a President wants to function as a mindless thriller that eventually makes us think — and only after the film is over question the form that encouraged us to be mindless. These are incompatible agendas, and in the end neither is fully successful.