From the December 4, 2004 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Million Dollar Baby

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Paul Haggis

With Eastwood, Morgan Freeman, Hilary Swank, Jay Baruchel, and Mike Colter

The Aviator

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by John Logan

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Cate Blanchett, Alec Baldwin, Alan Alda, John C. Reilly, Kate Beckinsale, Adam Scott, and Ian Holm

Despite his grace and precision as a director, Clint Eastwood, like Martin Scorsese, is at the mercy of his scripts. But in Million Dollar Baby he’s got a terrific one, adapted by Paul Haggis from Rope Burns: Stories From the Corner.

This book was the first published work by Jerry Boyd, writing under the pseudonym F.X. Toole, after 40 years of rejection slips. Boyd had been a fight manager and “cut man,” the guy who stops boxers from bleeding so they can stay in the ring, and he was 70 when the book came out; he died two years later, just before completing his first novel. This movie is permeated by those 40 years of rejection, and the wisdom of age is evident in it as well. Henry Bumstead, the brilliant production designer who helped create the minimalist canvas — he was art director on Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and has been working for Eastwood since 1992 — will turn 90 in March, and Eastwood himself will be 75 a couple months later. All these years pay off in economy as well as observation.

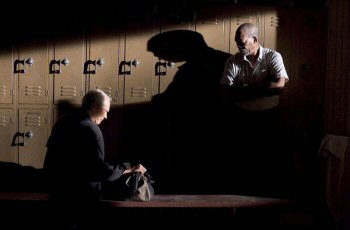

The offscreen narration is by a one-eyed ex-boxer named Eddie “Scrap-Iron” Dupris (Morgan Freeman), Scrap for short, who helps run a gym called the Hit Pit. But the story belongs mainly to his best friend, Frankie Dunn, the gym’s owner (Eastwood), and Maggie Fitzgerald (Hilary Swank), the 31-year-old hillbilly Frankie reluctantly agrees to train and manage. This leads to some awkward point-of-view issues concerning what Scrap saw and what he merely surmised or heard about that are problematic only if one chooses to focus on them. Having him recount events sometime after they happened only adds to the fatalistic noir atmosphere. As a boxing movie, this is every bit as grim as The Set-Up (1949) and Fat City (1972), and as an underlit look at a seedy American subculture, set mainly in a few lairlike locations, it’s as dark and doom ridden as the 1961 The Hustler (with which it paradoxically shares a ‘Scope format) and Eastwood’s own 1988 Bird.

I can’t think of many things I’m less drawn to than boxing. Million Dollar Baby tends to view it as neither an especially interesting sport nor a metaphor for something else (as Raging Bull does), but rather as a particularly acute form of savagery in a savage world. “Boxing is about respect,” Scrap observes early on, “getting it for yourself and taking it away from the other guy.” Yet unlike Raging Bull‘s Jake LaMotta, Maggie shows few signs of vengefulness or spite. She merely wants to make her mark in a world where she’s long been labeled trailer trash.

Apart from that, we know little about her past or about Frankie’s, and one of this movie’s triumphs is that it says as much as it does despite minimizing its backstories and offscreen space. The performances of the three leads are perfect, so we don’t care that we don’t know what lies right outside the Hit Pit. Unlike most other Eastwood films, this one has no sex, depicted or remembered. We know Frankie has a daughter and that he writes her every week, but the letters are all returned and we never learn anything else about her. We also know nothing about her mother. When we belatedly get an account of how Scrap lost his eye and how Frankie was involved, this information almost feels like a glut. We learn more about Frankie’s troubled Catholicism (he habitually attends mass and has an ongoing dialogue with a priest afterward) and his nurturing of his Irish roots (he studies Gaelic and reads Yeats) than we do about his everyday life, especially before he agrees to train Maggie. We never learn how Maggie spent her 20s. And the two glimpses of Maggie’s mother and some of her other family members may be more than we care to know.

Conservatives routinely link themselves to “family values,” yet this movie by a conservative filmmaker gives us one of the most negative views of family I’ve ever encountered. In a bleak world, where neither family nor religious faith offers any lasting respite, Million Dollar Baby offers redemption that derives from the informal and nameless loving relationships people create on their own rather than inherit from family, church, or society.

The movie’s most memorable image — included in the trailer, in spite of its apparent irrelevance to the plot — occurs in a filling station, when Maggie glimpses and waves at a little girl holding a puppy in the front seat of an adjacent truck, a character we never see again. Later we see Maggie and Frankie enjoying lemon pie together at a roadside joint. Such moments, though surrounded by ugliness, darkness, and violence, offer all the transcendence we need. In a context so close to despair, small but considered acts of kindness and fleeting moments of happiness carry the force of epiphanies.

Lots can be said for The Aviator as entertainment, though not much for it as edification. John Logan’s witty yet shallow script suggests we’ll learn something significant about the psychology of Howard Hughes (1905-’76), but it doesn’t deliver.

Logan and Scorsese held my attention for all 169 minutes — through the comic extravaganza of Hughes (Leonardo DiCaprio) blowing a wad on his first talkie (the 1930 Hell’s Angels), the spectacle of his building and flying planes while romancing all the pretty ladies in sight, and his intrigues as he defies and outwits corporate entities larger than his own, such as MGM, TWA, and the U.S. government. But then the movie concludes with Hughes repeating the phrase “the wave of the future” like a broken record, and I couldn’t figure out whether Logan and Scorsese were trying to illustrate a Hughes tic I hadn’t heard about, evoke the specter of future multicorporate takeovers, or simply distract the audience from its questions.

The movie starts off on the wrong foot by offering a scene of young Howard standing naked in a tub in an ornate living room while his mother sponges him down and teaches him how to spell quarantine, warning him about the horrors of typhus and “the colored.” It’s as if Logan and Scorsese wanted one pithy bit of psychological backstory that could account for the multifaceted craziness of Hughes as a grown-up, including his phobia of germs, his paranoia, and his reclusiveness. This is the only glimpse of his boyhood offered, and it’s less an explanation than a cover for the absence of one, a ruse to keep us from asking too many questions. It’s also a symptom of a cinephiliac malady that I’ll call an acute case of Rosebud — a need to make numerous visual and stylistic references to Citizen Kane even though they cloud more issues than they clarify.

I can guess how these references might have been rationalized. It’s well-known that Orson Welles considered making a film about Hughes before he opted for William Randolph Hearst; some of the details are in Welles’s autobiographical F for Fake. But it’s wise to remember that Kane is a fictional character and that the use of the word “Rosebud” as a key to unlock the mystery of his life is undermined in the film’s final speech: “I don’t think any word can explain a man’s life.” Using quarantine as if it were an equivalent of Rosebud, even in passing, is a sign that this movie is more interested in pop mythology than in getting to the bottom of any character, real or fictional.

Admittedly, keeping audiences from asking too many questions is one way of defining entertainment, and for the most part Scorsese does succeed as an entertainer. If we accept, contrary to some biographies, that Hughes’s romantic involvement with Katharine Hepburn was a major part of his life, we’re primed for one of the film’s most nuanced achievements in pop mythology and can sit back and enjoy Cate Blanchett’s crafty impersonation and Logan’s hilarious dialogue for her. (“I adore the theater,” she says. “Only alive onstage. I’ll teach you. We’ll see some Ibsen. If the Republicans haven’t outlawed him by now. You’re not a Republican, are you?”) And even if we can’t believe quite as readily in Kate Beckinsale as Ava Gardner, her character’s maternal sweetness is still touching.

Similarly, Scorsese’s climactic treatment of Hughes crash-landing his XF-11 plane in Beverly Hills — after scraping off the tops and sides of buildings — is a spectacular and highly suspenseful bit of bravura filmmaking that works best if we can overlook how people other than Hughes were affected. As Michael Atkinson notes in the Village Voice, “It’s hard not to wonder who else was hurt or killed in that crash, but their names are apparently lost to or bought out of history.” I wondered the same thing, and by not taking up the question Scorsese ultimately fails for me as an entertainer, though some will no doubt see the shock-and-awe crash as funny (as David Denby did). Others will be disturbed by the loose ends and reminded of our current tendency to overlook the casualties caused by “visionary” leaders.

The Aviator focuses on the early adulthood of Hughes — “during his scrappy years from the late 1920s to late 1940s,” as one piece of infotainment puts it, “when he fought the Hollywood establishment and pushed bounds on sex and violence in film, dated parades of starlets, and oversaw creation of the world’s biggest and fastest planes.” I was disappointed that it stopped just before Hughes took over the RKO studio and revealed contradictory aspects of his right-wing politics. He assigned several RKO directors a film called I Married a Communist in the late 40s and early 50s as a test of their patriotism, figuring that anyone who turned the project down was automatically suspect. Yet he also protected a leading Hollywood radical, Nicholas Ray, from being blacklisted so that Ray could patch up several Hughes features. But my ideal Hughes biopic isn’t Scorsese’s, which, as the title suggests, is mainly about the man’s obsession with planes — and about the wealth, power, and glamour of the youthful Charles Foster Kane.

A more charitable reading of this movie’s thematic thrust might say it broaches the mystery of how a dysfunctional obsessive managed to accomplish as much as he did, beyond what his billions bought him. This reading might even fit in with the Kane references insofar as the enduring popularity of Citizen Kane probably has more to do with a worship of power –Welles’s and Kane’s — than with an exploration of the title hero’s personal failings.

But by and large I think this movie’s chief function is to give Scorsese an opportunity to indulge in the pleasures of big-time filmmaking and to treat the audience to a heady dose of glamour — knocking our socks off with period re-creations of the Cocoanut Grove, Grauman’s Chinese, and two-strip Technicolor. All that’s justification enough for any entertainment, and on this level The Aviator does even better than most of Hughes’s own movies (not including Scarface, which he had the good sense to let Howard Hawks direct). There just isn’t a lot to chew on once it’s over. If you ignore most questions, you don’t wind up with many answers.