I can very happily report that since I first published this article, in the February 6, 2004 Chicago Reader, a few Barnet films have become available on DVD, including the two I wrote about, and a few more are reportedly on the way from Ruscico, a Russian label that has been issuing subtitled DVDs that I wrote about here. Earlier, Image Entertainment brought out Outskirts and The Girl with the Hatbox on a single DVD, and in France, www.bachfilms.com released both By the Bluest of Seas (under its French title, Au bord de la mer bleue), which Ruscico has subsequently released as well, and the 1943 A Good Lad/Men of Novgorod (again, under its French title, Un brave garçon). More recently, I showed clips from Okraina as well as other early Russian talkies (Deserter and Enthusiasm) in a course, “The First Transition: World Cinema in the 30s”, Kevin Lee has made a wonderful video about By the Bluest of Seas with a rapturous critical commentary written by Nicole Brenez, and in the summer of 2011, Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna presented a comprehensive Barnet retrospective, most of which I was able to attend.

Recently reseeing By the Bluest of Seas at the Arsenal in Berlin, as part of a program devoted to Frieda Grafe’s favorite films, I was more blown away than ever, and it struck me that the film could be viewed in some ways as an erotic view of collectivism and socialism, with the sea serving as a perfect emotional metaphor — and a perfect sort of reply to what Luc Moullet maintained in his review of Jet Pilot, which implied that eroticism, as in that film and The Fountainhead, was always tied in some fashion to right-wing thinking. For a sexy view of collectivism, it’s hard to think of any movie much better than this one. — J.R.

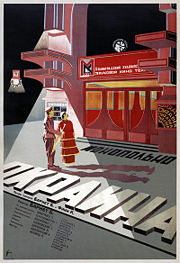

Okraina **** (Masterpiece) Directed by Boris Barnet Written by Kostantin Finn and Barnet With Alexander Chistyakov, Sergei Komarov, Yelena Kuzmina, Nikolai Bogolyubov, Nikolai Kryuchkov, and Hans Klering.

By the Bluest of Seas **** (Masterpiece) Directed by Boris Barnet and S. Mardanov Written by Klimenti Mintz With Lev Sverdlin, Nikolai Kryuchkov, Yelena Kuzmina, Andrei Dolinin, and Sergei Komarov.

His films convey more than most the intensity of happiness, the physical pleasure of meeting and contact, the inevitable tragedy of relationships. — Bernard Eisenschitz

The movies of Russian director Boris Barnet (1902-1965) are almost never screened, and information about his work is scarce. He seems to have made slightly over two dozen films, and I’ve seen three. Two of them, Okraina (1933) and By the Bluest of Seas (1935), are masterpieces. The third, The Girl With the Hat Box (1927), isn’t bad, though it’s far less memorable; curiously it’s his only film out on video. These three films and four others are showing at Facets Cinematheque this week, along with a film Barnet acted in (Lev Kuleshov’s 1924 knockabout farce The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks) and a recent film tenuously inspired by Okraina (and sharing the same English title, Outskirts).

Though many of his films were popular successes when they came out, Barnet is known among cinephiles mainly as the greatest forgotten master of the golden age of Soviet cinema. To the best of my knowledge, this is the only Barnet retrospective Chicago has ever had, and only one of his films has previously been covered in the Reader, The House on Trubnaya Square (1928, see above), which Dave Kehr reviewed enthusiastically and others have called the best Soviet silent comedy ever made. Jacques Rivette has called Barnet the best Soviet director after Eisenstein; Jean-Luc Godard has written about him with similar reverence, as has film historian Bernard Eisenschitz.

Barnet is missing from most film history courses, but clearly it’s not because he’s a minor figure. In 1971 French film and literary critic Raymond Bellour published an essay describing film in general as an “unattainable text.” In part he meant that movies — unlike poems, articles, stories, or books — weren’t things one could possess, keep on a shelf, quote from, and cherish as objects. They appeared briefly, and then they disappeared, often for good. Bellour might have added that because movies were elusive and unattainable for much of the 20th century, they had a mysterious, magical allure. Anything that’s here today and gone tomorrow remains fascinating precisely because it can’t be pinned down or filed away. But Bellour couldn’t have predicted that within a decade, videos — and later DVDs — would make many movies as attainable as printed matter, even if the conditions for watching them had changed. Some mainstream commentators might argue that most of the world’s important movies are already available on video or DVD, but Okraina and By the Bluest of Seas are hardly the only important works that aren’t available on either. Most mainstream critics and studios tend to be lazy about enlarging the canon, and so they probably don’t have a clue as to what all the important films are, since most of the films ever made aren’t on video or DVD. Of course some of the best films are available at the video store, but the mainstream goes on limiting its definition of classics to films everyone already knows.

The program at Facets is called “The Extraordinary Mr. Barnet,” and the use of the word “extraordinary” is by no means hyperbolic. Barnet’s paternal grandfather was an English printer who settled on the outskirts of Moscow, and Barnet himself was born there in 1902. He studied painting in Moscow before joining the Red Army in his teens and serving as a medic, and after the civil war he drifted into professional boxing. Lev Kuleshov, an influential film teacher as well as filmmaker, saw one of Barnet’s matches and cast him in a prominent role in The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks. Barnet joined the Kuleshov workshop as a student and handyman and eventually got to codirect a 21-reel serial called Miss Mend (1926); his first solo effort was The Girl With the Hat Box. Neither a theorist nor a very able propagandist, Barnet was too instinctive and physical a director to fit comfortably within any prescribed form of socialist realism, and his reputation for making American-style movies — apparently acquired partly because of his last name — eventually turned the state bureaucracy against him. At least this is the impression left by biographical accounts, which are all sketchy. Some American descriptions of his films emphasize their propagandistic elements, but his propaganda strikes me as either slight or as politically incorrect — the very attributes that likely got him in trouble. After sampling his work, I was shocked to learn that he committed suicide in 1965, leaving behind a note that said he seemed to have lost the ability to make good films.

Set in a Russian village during World War I, Okraina is Barnet’s first sound picture, and as in some other early Russian talkies — Alexander Dovzhenko’s Ivan, Vsevolod Pudovkin’s The Deserter, Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm — the stylized sound track is highly inventive and original. Within the first few moments cheers are synchronized with blasts of steam from a train engine, the sound of a roomful of cobblers hammering away at shoes registers like a bit of electronic music, and there’s even a horse that briefly speaks — a trope that’s easy to associate with Dovzhenko’s silent pictures.

The sound in Okraina has the curious, primal effect of redefining silence, as if we’d never experienced it before — a virtue that’s especially striking in relation to current movies, in which silence of any kind is a rarity. By punctuating extended stretches of silence with whizzing or whistling and then the sounds of explosions, Barnet sensitizes our ears as well as our nerves, and he rarely allows the dialogue to carry the story. There’s nothing intellectual or obtrusively formal about his decision to accord sound and image equal importance. This is a volatile film full of raw emotions, and as Russian film historian Jay Leyda once put it, “You can’t be sure whether the next scene will be funny or pathetic, gentle or violent.”

This is the kind of movie in which a soldier can play dead in the trenches as a practical joke, fooling us as well as his buddies, and where a young Russian woman can fall hopelessly in love with a German prisoner with whom she can barely communicate. Comic scenes can suddenly turn tragic, and vice versa. One melancholy long shot of a brooding soldier and a brooding woman seated on opposite ends of a bench ends with a gag: when the soldier stands up, the woman, as if on a seesaw, sinks. Seemingly irrational shifts in mood and plot ultimately create a profound sense of war as a state of chaos. (Some commentators have suggested that Barnet’s implicit pacifism led to his being accused of inaccurately portraying Russian life.) In some montage sequences, images of warfare go by so quickly they seem to pile on top of each other, and after a character rushes into a meeting to announce that the czar has abdicated, the senseless fighting doesn’t stop.

By the Bluest of Seas is a musical, codirected by S. Mardanov, that’s even more intensely physical than Okraina. Even though warfare is a passing offscreen issue, this film is as much about peace as Okraina is about war — a view of paradise to complement the previous glimpse of hell.

The plot is simple and concentrated. After shots of waves and an awkwardly translated opening intertitle — “A ship perished in the Caspian Sea / Young lives were fighting with death for two days” — we meet the two heroes, a sailor and a mechanic. They’re picked up by a schooner and taken to an island in Soviet Azerbaijan, where they encounter a young woman named Mashenka (Yelena Kuzmina), who heads a fishing co-op and works as a forewoman on a fishing boat. What little remaining story there is focuses mainly on the romantic rivalry between the two men, though Mashenka eventually reveals that she has a fiance who’s off fighting in the Pacific.

It’s difficult to account for what makes this movie so exquisite, apart from the characters and their quirks (such as one man’s ticklishness) and the beauty of the idyllic setting. Eisenschitz seems to be on the right track when he says that the film is unclassifiable, that it’s “certainly not a comedy even if it provokes laughter.” We wind up feeling affection for the three leads, partly because of the affection they show for one another and partly because of the gusto with which they show it. This aspect reminds me of some of Raoul Walsh’s character-driven comedies of the early 30s, such as Me and My Gal (1932) and Sailor’s Luck (1933) [see first photo below]. But there’s also an undertow of sadness that seems quite foreign to Walsh — a sense of melancholy wrapped around each moment of joy that seems quintessentially Russian.