From the Chicago Reader (October 3, 2003). — J.R.

A friend of a friend recently visited an uncle who’d just come back from fighting in Iraq. He conceded that the invasion hadn’t reduced the threat of terrorism or uncovered any weapons of mass destruction or exposed any links between September 11 and Saddam Hussein. “Just the same,” he said, “September 11 happened almost two years ago — and somebody’s got to pay.”

I was reminded of his words a couple days later at the Toronto film festival, when I saw Gus Van Sant’s Elephant — a fiction film about the 1999 killings at Columbine High School. No one has been able to adequately explain that massacre, and Van Sant doesn’t even try. Yet one of the teenagers’ motives may well have been “somebody’s got to pay.”

Elephant is Van Sant’s first decent film in years, but it made Variety‘s Todd McCarthy so indignant when it premiered at Cannes this past spring that his anger may have been the biggest news at that festival. This is less peculiar than it sounds, since the Cannes festival is held mainly for the press — unlike the Chicago festival, which is held for the public, or the Toronto festival, which is held for the press, the industry, and the public — and that creates an overheated critical climate where all the competing films are commonly declared either wonderful or terrible.

The notion that “somebody’s got to pay” is arguably an aesthetic principle rather than an ethical one — the kind of expectation bred by the dramaturgy of dumb action movies with revenge plots as well as certain sports events, all of which promote a knee-jerk idea of tit for tat. In contrast, some of the other best new films I saw in Toronto — Jafar Panahi’s Crimson Gold, Billy Ray’s Shattered Glass, and Marco Bellocchio’s Good Morning, Night, the first two of which are showing at the Chicago festival — take a stab at explaining a real-life crime before implicitly concluding that it can never be explained definitively. Bellocchio may come the closest as he probes the motives of Italy’s Red Brigade in kidnapping and killing Christian Democrat leader Aldo Moro in 1978. Panahi, working with a script by Abbas Kiarostami, offers a potent look at the class resentment of a middle-aged pizza deliveryman in Tehran who killed a jewelry-store owner and then himself in the course of an attempted robbery, but it’s entirely to the film’s credit that it doesn’t suggest that the man’s resentment explains everything. It’s equally to the credit of Billy Ray’s docudrama about the concocted journalism of New Republic reporter Stephen Glass that it’s interested less in Glass’s motives than in the motives of the colleagues who believed his many fabrications.

The nice thing about a film festival for the public rather than for the press or the industry is that neither publicists nor test marketers run the show. Before I went to Toronto I was getting almost as many daily e-mails from publicists representing films there as I was getting spam for penis enlargement. Some of these publicists invited me to special press-only shows, until I indicated that I wasn’t going to interview anybody — at which point I was hastily disinvited. Fortunately, I still got to all the films I most wanted to see, many of which I knew wouldn’t be opening commercially in Chicago anytime soon.

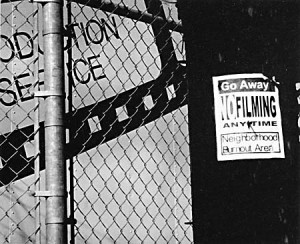

Despite dire warnings from reviewers who’d attended Cannes, I saw a lot of exciting things in Toronto. My favorite was a premiere, Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself, an almost three-hour compilation of clips with commentary on how Los Angeles is represented, misrepresented, and mythologized in movies. This dazzling piece of film criticism by an LA native, mixing social history and architectural analysis, transformed my understanding of Chinatown and dozens of other films and helped me clarify precisely what I disliked about L.A. Confidential. Despite a thoughtful rave review in Variety, it could still take months for this epic meditation to reach Chicago.

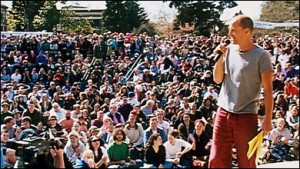

Los Angeles Plays Itself shares an interesting trait with a Chicago festival selection from Canada, Ron Mann’s Go Further, the runner-up for the people’s choice at the Toronto festival: it’s a radical statement so easy to take that it doesn’t even seem political. Young malcontents who are sick of being browbeaten for not having been around in the 60s may appreciate Andersen’s and Mann’s strategies for circumventing shopworn leftist rhetoric. Virtually all of Los Angeles Plays Itself is about class, yet only the last 15 minutes or so deal with it directly. Go Further is a pitch for organic living and the like, but it registers more like a lark than a sermon.

Ever since the evening news became a display of bootlicking interspersed with press releases, documentaries in movie theaters have been a lot more popular. Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine — perhaps the principal source of American reviewers’ ire at Cannes last year — has already brought in well over $50 million, making it by far the most commercially successful documentary in the history of movies, though it’s hardly the only one that’s been doing well lately. This doesn’t mean that Moore’s any less of a manipulator than Steven Spielberg, but it does suggest that audiences no longer see the official pieties that dominate TV as adequate. Go Further is the only one of the dozen features showing in the Chicago festival’s documentary competition that I’ve seen, though I’ve heard praise for a couple of the others, The Revolution Will Not Be Televised and S21: The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine.

Altogether, I’ve seen only about 20 of the 100 programs showing at this year’s festival, but I like practically all 20. The best by far is Yasujiro Ozu’s 1932 I Was Born, But…, showing as Roger Ebert’s critic’s choice. This is the greatest film by one of the world’s greatest filmmakers, a comedy with tragic undertones about two young brothers who arrive at a painful discovery about their father and the world in general. That it’s silent shouldn’t put anyone off. Those familiar only with Ozu’s talkies may know him as a slow and technically frugal director, but here the speed of some of his camera movements is breathtaking. Silent Japanese films had explainers and narrators known as benshis, who became so popular that the Japanese commonly went to movies to see their favorite benshi rather than their favorite actor. The benshis were so powerful that silent cinema lasted longer in Japan than anywhere else. Midori Sawato, one of the very few contemporary benshis, will be performing live with this screening, which makes it a must-see.

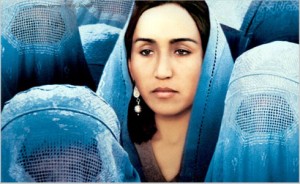

My own critic’s choice is Manoel de Oliveira’s 1975 Benilde, or the Virgin Mother, which I selfishly programmed because I wanted to see it again — it’s not an obvious crowd-pleaser. Another of my favorites is Michael Wilmington’s selection, Wild River (1960), one of the finest but most neglected of Elia Kazan’s features. Among the new films I’d recommend, roughly in descending order of preference, are Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn (though its minimalism makes it off-putting at first), Panahi’s Crimson Gold, de Oliveira’s A Talking Picture, Hakim Belabbes’s Threads, Mann’s Go Further, Tsai’s 23-minute The Skywalk Is Gone (showing in one of next week’s shorts programs), Lee Chang-Dong’s Oasis, Rolf de Heer’s Alexandra’s Project, Ray’s Shattered Glass, Raul Ruiz’s That Day, Catherine Breillat’s Sex Is Comedy, Hana Makhmalbaf’s Joy of Madness, Samira Makhmalbaf’s At Five in the Afternoon, and Alejandro Chomski’s Today and Tomorrow.

Joy of Madness is an eye-opening and sometimes hilarious account of 22-year-old Samira Makhmalbaf’s aggressive, increasingly desperate efforts to drum up a local cast in Kabul for At Five in the Afternoon, as recorded by her 14-year-old sister, Hana. As with Les Blank’s 1982 Burden of Dreams, a documentary about the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, this documentary is in some respects more interesting than the film it’s about.

I would normally disapprove of the shameless hyperbole in Oasis and Alexandra’s Project — the first is a love story about two disabled South Koreans, the second an exceptionally vicious Australian revenge tale — but I can’t help applauding their virtuosity and intensity.

It’s interesting that films from the Middle East can come into the U.S. without much hassle, even though to the best of my knowledge no Middle Eastern filmmakers, apart from Israelis, are currently allowed to. Last fall U.S. customs said it would take three months to clear Abbas Kiarostami of any suspicion that he was a terrorist, forcing him to cancel his trip to the New York film festival. My first selection for a critic’s choice at this year’s festival was a group of new experimental shorts by Kiarostami shot on DV near the Caspian Sea and called 5 Long Takes [later released as Five], but logistical and legal complications prevented them from making it into the festival.

I got to see them only late last month at an exhaustive Kiarostami retrospective in Turin, where the filmmaker was also presenting a couple of gallery installations — long takes showing a placid couple sleeping for 90 minutes and a fretful infant for 10. In an interview Kiarostami said, “I heard that Andy Warhol made a 24-hour film of his wife sleeping, but at that time digital video didn’t exist yet; I don’t know how he managed” — an amusing jumble of misinformation about Warhol’s six-hour Sleep (1963), which actually consists of many shots filmed from different angles of poet John Giorno sleeping. But misinformation — about Warhol having a wife who slept for 24 hours, about Kiarostami being a potential terrorist, about Samira Makhmalbaf possibly poisoning an Afghan baby she wanted to use in her film — is part of the everyday comedy of multilingual international exchanges, and ultimately only a subtext to the larger edification that can come about through international film events. The heady and sensual pleasures of cultural exchanges are among the gifts the 39th Chicago International Film Festival offers us, and so you might be wise not to restrict your choices to the preferences of our reviewers.

Screenings this year are being held through October 16 at Landmark’s Century Centre (2828 N. Clark) and the Music Box (3733 N. Southport). Single ticket prices are $6 for weekday matinees (Monday through Friday before 5 PM) and $10 for all shows after 5 PM ($8 for Cinema/Chicago members). Passes for everything but opening night, I Was Born, But…, and closing night are also available, good for up to two tickets per screening; they cost $50 (six tickets, seven for Cinema/Chicago members), $110 (16 tickets, 18 for Cinema/Chicago members), or $250 (50 tickets). The special presentations, which include critic’s choice programs, are $15 ($13 for Cinema/Chicago members). Tickets can be purchased at theater box offices at least one hour before the screening; they can also be bought in advance (Cinema/Chicago, 32 W. Randolph, suite 600; Borders, 2817 N. Clark and 830 N. Michigan), by fax (312-425-0944), or by phone (312-332-3456; Ticketmaster, 312-902-1500). For more information call 312-332-3456.