The following review of Lost in La Mancha appeared in the February 21, 2003 issue of the Chicago Reader. Seeing the newer Terry Gilliam film, The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus (see above), last Saturday (November 7), on my last evening in St.. Andrews, Scotland, I was sufficiently blown away by the visual invention and surrealist imagination on display here to rethink some of my estimation of his films. (The film wouldn’t open in the U.S. until Christmas, but I was told that it was already something of a monster hit in Europe.) Even though I couldn’t always follow what was going on in terms of plot (probably my fault more than the film’s), the way Gilliam solved the seemingly insoluble problems posed by the death of Heath Ledger in the middle of shooting — arriving at a form of multiple casting (see below) that I’ve formerly associated mainly with experimental filmmakers such as Yvonne Rainer — is only one example of his nonstop ingenuity. I was also impressed by both his digital mastery and his arsenal of references — including The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T., which I believe he quotes from in one image of the hero climbing a ladder that rises into seeming infinity. —J.R.

Lost in La Mancha

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe

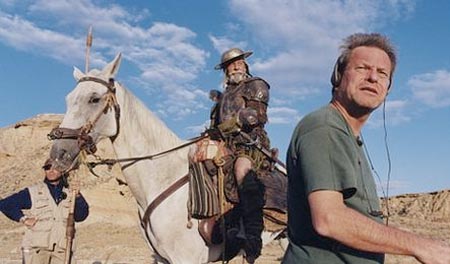

With Terry Gilliam, Jean Rochefort, Johnny Depp, Nicola Pecorini, and Philip Patterson, and narrated by Jeff Bridges.

Don Quixote is a fairy tale. So is Bleak House, so is Dead Souls. Madame Bovary and Anna Karenin are supreme fairy tales. But without these fairy tales, the world would not be real. — Vladimir Nabokov

Lost in La Mancha, which opened last week at Landmark’s Century Centre, started out as a documentary about the making of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, a Terry Gilliam feature about the delusional don. But Gilliam encountered a string of setbacks in Spain in September 2000 — a soundstage in Madrid with lousy acoustics, terrible weather, overhead jets, the lead actor (Jean Rochefort) delayed by a prostate problem that got so bad he had to bail out — and the producers decided to close down the costly production by the second week. So Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe wound up making their film about the unraveling of the Gilliam project. It’s a sad story, though far from an uncommon one, and it may tell us more about films that do get made than about ones that don’t. Orson Welles once said a director is “someone who presides over accidents,” and I might add that it’s only the films that encounter relatively small accidents that we ever get to see.

Gilliam keeps up a brave and cheerful front throughout the cascading mishaps. We know from the outset that he’s wanted to launch the project for at least a decade, and at the end of this documentary he still hasn’t given up. And it’s clear how personal the project is when we see him gleefully acting out various roles during production meetings and rehearsals.

The trade press described him as a megalomaniac when he was battling with producers over Brazil (1985) and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1989), but my impression when I met him five years ago was that this was studio propaganda. He seemed much closer to a laid-back hippie, and this, more or less, is how he comes across in Lost in La Mancha.

However, Gilliam was once a cartoonist, and some cartoonists are quiet megalomaniacs–having specific visions of how things are supposed to look and accustomed to controlling every inch of available space. This isn’t a problem when the space consists of a piece of drafting paper, but things get more complicated once the space becomes a soundstage or a location filled with crew and cast members.

Controlling space with a prefigured design isn’t of course the only way for an artist to make films, though this documentary often seems to imply that it is. Transferring a vision to film requires translation, and the act of creation in one medium must be kept at a remove from its realization in another. Yet there’s another kind of film art dedicated to invention on the spot — within the act of filming, generated by actors as well as directors — that’s devoted to seeking rather than finding.

Early on in the proceedings we’re given a few glimpses of what the filmmakers indicate is Welles’s unfinished and unreleased film Don Quixote, which he worked on from the mid-50s until his death in 1985. There’s also the suggestion that Welles went through a monumental struggle trying to get his vision of the novel onto the screen. I’ve been lucky enough to see over two hours of edited and unedited footage from this major lost work, and it seems to me that it was made with relatively little struggle and a great deal of joy. (I’ve also seen a couple hours of Welles’s unfinished The Other Side of the Wind and The Deep, and I regard his Quixote material as superior in most respects and as one of the greatest achievements in his career.) Unlike Gilliam, Welles improvised, and much of his footage was shot silently and very cheaply with lots of exuberance and invention — though also with tragic undertones and an earthiness worthy of Chimes at Midnight. Akim Tamiroff — who was magnificent in Welles’s Mr. Arkadin, Touch of Evil, and The Trial — gives perhaps his greatest performance, as Sancho Panza, though his lines (like those of Francisco Reiguera, who plays Quixote) are dubbed by Welles.

Most important, the film was owned exclusively by Welles as long as he was alive, so he never had to worry about producers taking it away from him and mangling it. The one time I met him, in 1972, he told me it was virtually finished, apart from the music and some of the sound. But he said that he didn’t want it to compete with Man of La Mancha, which was about to open, and that he intended to release it in his own good time, under the title When Will You Finish Don Quixote? Considering the circumstances of his career, who could blame him? I’m sure he hung on to the film and kept retooling it because he got so much pleasure out of it and because he knew full well that once it was out of his hands it would probably be recut by idiots and then either stomped on or ignored by critics — which is precisely what happened after he died.

I’ve also been unlucky enough to see the boring two-hour atrocity made from poorly duped parts of Welles’s Quixote intercut with parts of a routine documentary series about Spain he made for Italian TV. The thing was quickly cobbled together by Spanish hack director Jesus Franco in 1992 — shortly after Gilliam started incubating his own version — and this is the version we’re shown samples of in Lost in La Mancha. It’s lamentable that the Welles Quixote remains out of reach while the Franco Quixote calling itself the Welles Quixote is what we get here. After all, Welles’s film was made out of love, Franco’s for money and glory, though he reaped very little of either. Welles’s footloose and mercurial nature apparently drove him to say to separate individuals on separate occasions, “You are the only one I can trust,” including Mauro Bonanni, the Italian editor of Quixote, who still clings to some of the footage, and Welles’s longtime companion Oja Kodar, who inherited the rest and then sold it to the Filmoteca Española in Madrid. As a consequence, the film survives today only in scattered fragments held by disputing factions. Given Welles’s avowed lack of interest in posterity, this might be the sort of outcome he would have wanted.

But it does survive, and I’d like Lost in La Mancha more if it didn’t take the easy but misleading route of dovetailing Gilliam’s frustrations into Welles’s, and then dovetailing both into Quixote’s. It is good to see something of Gilliam’s conception for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, conveyed partially through his drawings and storyboards (some of which are animated in a rudimentary fashion) and partially through his directing work, including a few glimpses of the material he managed to shoot. But when it comes to the conceptions of Welles and Cervantes, Fulton and Pepe come up with nothing more than received wisdom, and this proves to be obfuscating in both cases.

I haven’t read the Cervantes novel since college, but I remember being shocked by the disparity between its reputation and how it reads — one of the subjects Vladimir Nabokov addressed with particular sharpness in the lectures he gave on the novel at Harvard in the early 50s. For one thing, people tend to think of it as a single book, when it more nearly qualifies as a novel and a sequel, like Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, written several years apart. (There may be further if limited parallels between the pairs of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza and Huck and Jim, including the lessening of narrative interest in both novels when the two characters are separated.)

Cervantes’s first novel is in many ways as crude and as cruel as a Three Stooges comedy, though it’s commonly perceived nowadays through a sweet tempered and innocent haze, as if the Stooges had somehow become transmogrified into Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd. The second novel, which incorporates the publication and reputation of the first in its plot, is more the source of the mythical resonance the whole story is remembered for. The don’s delusions that the age of chivalry persists, brought on by excessive reading of medieval romances, makes him the butt of jokes and pranks throughout the novel, provoking the derision of Panza (when he isn’t using his common sense to help the master out of various scrapes), other characters, and of the reader. Yet eventually his persistence gives him a certain nobility, and his deathbed renunciation of his follies becomes one of the most devastating tragic endings in all of literature.

The major link between the Gilliam and Welles versions of the story is a compulsion to make Quixote and Panza contemporary yet mired within their own historical period. Gilliam’s plan seems to have been to turn Panza into a contemporary character named Toby Grisini (played by Johnny Depp) who’s transported back into Quixote’s era, presumably like the hero of Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Welles kept both characters in their own period in terms of dress, speech, and manners, but planted them in contemporary Spain, making them even more absurdly archaic in their medieval escapades; he derived part of his comedy from the uncanny juxtapositions, such as the don and Panza occupying the same shots as neon signs for Quixote beer.

“The Windmills of Reality Fight Back,” Gilliam scrawls wistfully across one of his Quixote drawings toward the end of Lost in La Mancha, after his production has been shut down. A little earlier he remarks, “I’ve done the film too often in my head….Is it better to just leave it there?” As I suggested above, this is a sad but common lament about what depending on other people’s money often entails. The rare good movies that get made under these conditions can only be seen as miracles.

Yet as Nabokov was wise enough to note half a century ago, the “windmills of reality” — not only economics but luck and circumstance — are as much human constructions as the giants of Quixote’s fantasy, and it’s artists such as Cervantes, Gilliam, and Welles, not just the interests supporting them, who help to construct those windmills. More help, as Welles was wise enough to recognize, is provided by the creative collaboration of the audience. It’s important when speaking of failure to acknowledge both sides of the equation: from one point of view, Lost in La Mancha charts the failure of a project as a result of bad luck; from another — voiced most often by Gilliam’s assistant, Philip Patterson — the failure is a consequence of poor planning that didn’t allow for the intrusion of bad luck. The “windmills of reality” intrude in both cases, but how they’re interpreted is left to the audience.

For my money, the best Gilliam feature to date is the only one prior to The Man Who Killed Don Quixote that’s recalled in Lost in La Mancha as an unmitigated disaster, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen — a fantasy that does some of the uncanny things with scale and vision that Italo Calvino is remembered for in his story collection Cosmicomics. But when Gilliam and his producers speak of disaster I suspect they mean different things, neither of which coincides with my experience of the film. He probably means bad luck, and they almost certainly mean financial loss. By the same token, if a low-budget documentary like Lost in La Mancha winds up succeeding in the marketplace where The Man Who Killed Don Quixote never was launched, some of the credit belongs to Gilliam.