From the Chicago Reader (September 13, 2002). — J.R.

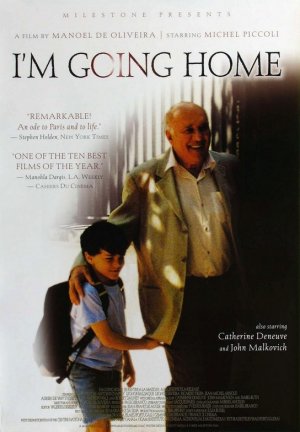

I’m Going Home

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Manoel de Oliveira

With Michel Piccoli, Antoine Chappey, Catherine Deneuve, John Malkovich, Leonor Baldaque, and Sylvie Testud.

It seems entirely fitting that I’m Going Home — a beautiful feature by Manoel de Oliveira, who turns 94 this December and is still going strong — should open in Chicago, at the Music Box, just after September 11. This 2001 French film by a Portuguese master who occasionally makes films in France is the kind of quiet masterpiece that fully registers only after you’ve seen it — a profound meditation on bereavement and other kinds of loss (including losing one’s way) as well as on everyday life and things right under our noses that we accept as “other,” including old age and art and different cultures.

The French DVD of this film has an interview with Oliveira in Portuguese, subtitled in French, in which he explains what this movie means to him. He speaks alternately about the film’s plot, which he calls a tragedy, the real incident that inspired it (a famous actor in his 70s forgot his lines while shooting a film), and what he calls the “tragedy of our civilization.” He speaks about globalization and modernization, ecological destruction, dehumanization, and people’s dependence on gadgets and objects — the last two epitomized by a man he saw speaking on a cell phone. “What can happen with a man can happen with a society,” Oliveira says, “or rather with civilization.” The film makes reference to the tragedy of our civilization only metaphorically, and unless I missed something, it never shows a cell phone. What it does show is a very private kind of grieving for personal loss that becomes public and universal once we reflect that there are always connections between individual lives and collective destinies.

At the very beginning of the film, the aging actor discovers that his wife, daughter, and son-in-law have all just been killed in a car accident. One reason Oliveira may have chosen to tell this sort of story is that part of what must be difficult about being old is living with the loss of so many friends and relatives. Yet this film, without a trace of sentimentality or false elation, is the lightest depiction of grief and the loneliness of growing old one could imagine. And while the film’s key word may be “solitude,” it’s mostly about savoring life in all its richness.

Five years ago French critic Raymond Bellour wrote a letter that was part of a collection of exchanges about cinephilia published in Trafic under the title “Movie Mutations.” It’s worth quoting at length: “Curiously, the word ‘civilization’ springs to mind. A word far greater than ‘cinema,’ its life or death, but which is itself also interior. There is a name that goes with this word: Oliveira….Oliveira’s preoccupation is, to put it banally, the fate of the world, how to live and die, survive in harmony with the logic of an ancient and prestigious country, which was fortunate to discover the world when it was worth discovering, and the strange destiny of having in part escaped the worst conflicts of this century thanks to a cruel and miserable dictatorship. He is, I believe, the only filmmaker who knew how to tell, in a unique film, the history of his country, from its founding through a melancholy myth up to the end of its empire (No, or the Vainglory of Command [1990])….Thanks not only to the extreme beauty of the images and a stunning vision of the capacities of the shot and of editing, Oliveira shows in all his films a profound sense of culture and art, of their place in everyday life as well as in collective memory. In short, he’s a great, immense artist, and above all a profoundly civilized man, one who is hyper-conscious, terrified that his civilization is ending, that his country is succumbing to Europe, that Europe is the shortest route to America (recall the old peasant woman’s monologue in Voyage to the Beginning of the End of the World [1997]).”

I’m not sure “terrified” is the best word for an artist for whom meditative stillness and calm observation are so central. But this is still a remarkably perceptive description — of a body of work that began with a silent documentary in 1931 and of the half dozen features Oliveira has released since Bellour’s words were published. (I’m guessing it still applies to his most recent film, The Uncertainty Principle, which I’m looking forward to catching up with next month at the Chicago International Film Festival.) It might be argued that Oliveira’s track record was uneven during the 80s and early 90s, with films as good as No often followed by ones as dull as The Divine Comedy (1991). But ever since the 1997 Voyage he’s clearly been on a roll. Inquietude (1998), The Letter (1999), Word and Utopia (2000), Oporto of My Childhood (2001), and now I’m Going Home form the most impressive string of masterworks I can recall seeing from anyone in years. Each one is different, and Inquietude and I’m Going Home are especially impressive.

“The past is a foreign country,” L.P. Hartley wrote in his novel The Go-Between. “They do things differently there.” It’s also true that the way most of us relate to the past and to history is connected to the way we relate to old age — if only because the elderly give us a direct pipeline into that faraway place. Part of what’s so fascinating about Oliveira’s late period is the way it fuses his fascination with foreign countries and his preoccupation with memory and history. To the best of my knowledge, the French strand in his work is first apparent in Nice a propos de Jean Vigo (1983) and Mon cas (“My Case,” 1987) and is picked up again a decade later in Voyage, which explicitly explores crossovers between Portuguese and French culture through a semiautobiographical story of a road trip taken by a Portuguese director (Marcello Mastroianni in his last performance) and a French actor with a Portuguese father. After the all-Portuguese Inquietude, which is largely about old age, comes The Letter, a modern-day French adaptation of the first French novel, La Princesse de Cleves, starring Mastroianni’s daughter Chiara. That’s followed by a piece of Portuguese history, Word and Utopia, about a 17th-century Jesuit priest, and a highly inventive and fanciful documentary about Oliveira’s hometown, Oporto of My Childhood. Then he returns to France and old age in I’m Going Home. In all of these films, he’s traveling enormous distances of different kinds, and the remarkable thing is how smooth he makes the journey.

Perhaps the two most off-putting things about I’m Going Home are its simplicity and its patience. Oliveira knows how to both peel away all the things that aren’t important and sit still for all the things that are — but sitting still for things that simply are as opposed to things that snap, crackle, and pop isn’t always easy. Roughly the first 13 minutes of the film after the opening credits are the last 13 minutes of a performance of Eugene Ionesco’s play Exit the King, starring the film’s leading character, a famous actor named Gilbert Valence (Michel Piccoli), as the king. (Catherine Deneuve plays the queen.)

I’ve never read or seen this play, but I don’t believe that’s necessary to understand what Oliveira is doing here. By the same token, we don’t need to be familiar with the sources of the two other roles we see Valence performing — Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Buck Mulligan in the opening scene of an adaptation of James Joyce’s Ulysses, directed in a French studio by an American (John Malkovich). It’s more important that at the beginning of the film Valence is playing a crumbling, ancient monarch who’s older than he is, speaking French in a French play; in the middle he’s playing an exiled wizard closer to his own age, speaking French translated from English; and at the end he’s trying to play a character drastically younger than himself, speaking English. The last role is in a ridiculous Euro-pudding production of Ulysses, a story set four years before Oliveira was born; we’re asked to sit still for Valence’s makeup session, and we also watch the shooting of the opening scene twice, on successive days. (The first time, we watch mainly Malkovich and his reactions — good acting to offset the bad acting we’re hearing.)

Watching the final scene of the absurdist Exit the King, the unwary viewer may be confused by the infantile regression of a king who’s about to die but also may be distracted because most of the time Valence has his back to both the theater audience and the camera (though Piccoli can act with his back almost as well as Erich von Stroheim could act with the back of his neck). This is characteristic of Oliveira’s approach to action in many scenes, an approach that deserves to be called essentialist rather than minimalist. For the essential part of the action here isn’t what’s occurring onstage; rather it’s the arrival of three men, who go first to the auditorium upstairs, then appear backstage. They carry the horrible news about the deaths in Valence’s family, conveying this information to him off camera in his dressing room after the curtain calls. At the same time, the other actors (and we) learn the news backstage and remark that the only family Valence now has left is his young grandson, Serge.

Maybe because Oliveira pares away all the emotional as well as narrative inessentials he’s free to show us all the things that remain in Valence’s life that give him pleasure: simple rituals such as drinking espresso at the same table at his favorite cafe while reading the Paris daily Liberation, which he rolls up while paying the waiter. This leads to one of the film’s best gags — executed in a series of pans involving another cafe customer who reads Le Figaro and fancies the same table — and it’s characteristic of Oliveira’s treatment of various work and leisure rituals that he repeats camera angles when he returns to a location. (Kenji Mizoguchi and Hou Hsiao-hsien are also masters of this method of establishing certain visual and thematic rhymes, which they also use to evoke long-term memories.)

Some of Valence’s other pleasures — captured incandescently in Piccoli’s perfectly pitched and seemingly effortless performance — include watching his grandson playing from his upstairs bedroom and at times joining his play in the living room, buying a new pair of shoes (which are soon stolen when he’s held up on the street), looking at a strange painting in a shop window (which attracts the attention of a clerk and two teenage girls, who all ask him for autographs), and listening to the film’s theme song as played by an organ-grinder on the street (the sweet and archetypal “Sous le ciel de Paris,” or “Under Paris Skies”). The extraordinary sound presence of this film–all the more remarkable given that Oliveira, like Luis Bunuel when he was making his last films, has become hard-of-hearing — plants us in the real as well as the mythical Paris in a way few other films can, as do the shots of (and from) the Eiffel Tower and of the fairgrounds at Concorde.

Yet Oliveira is also fully capable of focusing on only the feet of Valence and his agent, George (Antoine Chappey), during much of one scene in a cafe. One reason for this may be that Valence has just bought the shoes and they’re about to be stolen; another may be that Oliveira wanted a relatively neutral visual accompaniment to what the men are saying, which is extremely important. George wants to hook up Valence with an attractive young actress (Leonor Baldaque) who admires him — partly because he wants the two to star in a lucrative “TV thing” he’s trying to set up, which he thinks will make Valence more marketable, and partly because he believes a fling with an ingenue would make Valence happy. Valence thinks George is deceiving himself and devaluing Valence’s common sense and integrity, and he says so bluntly. Yet when he later agrees to fill in at the last moment in a part that’s far too young for him, in a language he can’t master, he realizes — as we do — that he was sucked in by the prestige of doing Joyce as well as by his own vanity.

Unless we’re old ourselves, we have a tendency to push old age (and a concomitant sense of history) to the back of our thoughts, much the way we’re apt to marginalize our thinking about life in other countries and cultures — even if we or our predecessors came from them. (Surely a part of the American dream has something to do with being able to travel lightly — which often means without much history to weigh us down.) If old age is treated by most of us as if it too were a foreign country, this isn’t because old age isn’t familiar or recognizable but because we prefer not to be held back by it. Yet Oliveira doesn’t seem to be held back by it at all — perhaps because he knows that even if the past is a foreign country for most of us, he’s lived there for some time and has plenty to teach us about it. He’s at least 20 years older than Valence in I’m Going Home, comes from another country, and is a filmmaker rather than an actor. Yet he knows this man like the back of his hand. He never shrinks from Valence’s grief, but he honors its essential privacy. Significantly, when an early scene shows Valence looking at a family photograph in his bedroom, we don’t see the photograph, only the way he’s looking at it.

In terms Hollywood producers would understand, Oliveira cuts to the chase — though the chase in this case is the world we live in and the life we value, including the small things. This no-nonsense approach yields a glorious film full of revelations–all of them light and many of them playful, but not one of them despairing, for all the grief they depict. At a time when war drums are thudding, these quiet thoughts are music to the ears.