From the June 5, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

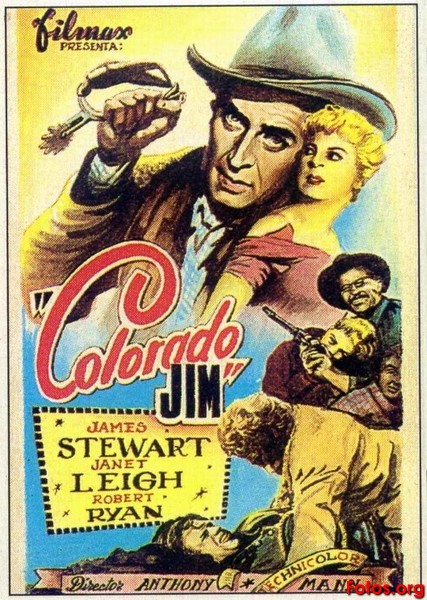

The Naked Spur

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Anthony Mann

Written by Sam Rolfe, Harold Jack Bloom

With James Stewart, Janet Leigh, Robert Ryan, Ralph Meeker, and Millard Mitchell.

Man of the West

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Anthony Mann

Written by Reginald Rose

With Gary Cooper, Julie London, Lee J. Cobb, Arthur O’Connell, Jack Lord, John Dehmer, Royal Dano, and Robert Wilke.

Q: What is the starting point for The Naked Spur?

A: We were in magnificent countryside — in Durango — and everything lent itself to improvisation. I never understood why almost all westerns are shot in desert landscapes! John Ford, for example, adores Monument Valley, but I know Monument Valley very well and it’s not the whole west. In fact, the desert represents only one part of the American west. I wanted to show the mountains, the waterfalls, the forested areas, the snowy summits — in short to rediscover the whole Daniel Boone atmosphere: the characters emerge more fully from such an environment. In that sense the shooting of The Naked Spur gave me some genuine satisfaction. –Anthony Mann in a 1967 interview

This seems to be landscape week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, with Abbas Kiarostami’s sublime Where Is the Friend’s House? (1987), Jon Jost’s mesmerizing Muri Romani (2000), and two terrific, eye-filling Anthony Mann westerns, The Naked Spur (1953) and Man of the West (1958). There are plenty of differences between these offerings. Muri Romani consists of nothing but extended overlapping dissolves between various exterior walls in Rome, each one slowly merging into the next, yet it’s so beautiful and absorbing I didn’t feel deprived. In fact, all of these films are uncommonly beautiful objects that do more with natural settings than most films do with characters — and to risk a pun, this isn’t all they do by a long shot.

All four films collapse the usual distinctions between landscape and architecture, classicism and modernity, and even at times painting and drama — though Muri Romani has no landscape in any ordinary sense and The Naked Spur, shot entirely in natural exteriors (apart from a cave where the characters find shelter from the rain), has no architecture. In contrast, Where Is the Friend’s House? focuses for long stretches on an ancient village clinging to the side of a mountain, and Man of the West features a farmhouse at the bottom of a green valley and a ghost town surrounded by mountains; both movies have a kind of compositional power that’s inextricably tied to their views of human behavior and human destiny.

Jean-Luc Godard wrote a review of Man of the West when it came out, describing “the delightful farm nestling amid the greenery which George Eliot would have loved.” If he’d written his review two years later he might have no less aptly connected the ghost town to the modernism of Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura. His view of Mann merged image and idea, classical and modern: “Just as the director of The Birth of a Nation gave one the impression that he was inventing the cinema with every shot, each shot of Man of the West gives one the impression that Anthony Mann is reinventing the western, exactly as Matisse’s portraits reinvent the features of Piero della Francesca….In other words, he both shows and demonstrates, innovates and copies, criticizes and creates.”

Mann (1906-’67) is still cherished today by aficionados of golden-age Hollywood. In the latest issue of CineAction, Robin Wood, perhaps the best critic of that cinema, ranks him alongside George Cukor, John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Leo McCarey, Max Ophuls, Otto Preminger, Nicholas Ray, Douglas Sirk, and Preston Sturges — all of whom, he notes, “retain their amazing freshness and vitality today.” If Mann is less known than the others it may be because his painterly gifts tend to wither on TV screens. Painter-critic Manny Farber first recognized these gifts in the late 40s and early 50s, when Mann still had the “museum space” afforded by 35-millimeter — resurrected today only in special screenings, such as the Film Center’s.

The Naked Spur, the most elemental Mann western and my favorite of all his pictures, has the most breathtaking scenery, including snowcapped mountains, rock formations, and green forest clearings in the Colorado Rockies near Durango. Yet insofar as westerns are intrinsically mythological, I suppose one could argue that this one might as well be taking place inside Mann’s head.

Part of the elemental lure of that western mythology today — comparable in some ways to the spell exerted by the Knights of the Round Table in England — is the excitement of an existential context in which characters forge their own personal destinies the moment they encounter or take leave of strangers. You won’t catch people in a western saying “No problem” or “Have a good one” to one another as a ruse for avoiding such challenges. The role of nature in these transactions, as Mann suggests, is to make the characters “emerge more fully”; as critic Donald Phelps once put it, “The great open spaces are sectioned as methodically as a football field.”

With the exception of a few nameless Blackfoot Indians killed in a brutal ambush — whom the film lamentably discounts, though the white man responsible for the ambush is no sort of hero — the film has only five characters. And because it never leaves the spectacular wilderness and everyone’s traveling light, no one has a single change of wardrobe — which somehow seems fitting for a landscape film. Moreover, the four male principals, as is typical in Mann westerns, all develop dialectically: Howard Kemp (James Stewart), the bounty-hunter hero, starts off as unpleasantly self-centered in relation to a friendly old prospector (Millard Mitchell), a dishonorably discharged yet resourceful cavalry lieutenant (Ralph Meeker), and even the cheerful outlaw (Robert Ryan) Kemp captures. Kemp becomes vulnerable when his leg is injured and bits of his tainted past are revealed (physical pain and traumatic back stories are central in Mann’s westerns), and only then do the three other men begin to show their darker natures, sparking an intense psychological war (another Mann specialty). The prospector and ex-officer insist that Kemp make them his partners and split the reward for capturing the outlaw three ways, and the outlaw contrives to unravel the complacencies of all three as they travel through the wilderness toward Abilene. When the prospector, aiming his shotgun at one of the others at a critical juncture, complains, “It’s gettin’ so I don’t know which way to point this no more,” he could just as well be speaking for the audience. As usual in such a fluctuating context, the role of the woman — a feisty orphan (Janet Leigh) the outlaw has in tow — is to represent all that’s left of civilization, a value that’s also prone to change as loyalties and ethical profiles shift.

The settings in Man of the West — a western town, a train bound for Fort Worth, a farmhouse in a valley, a desert, and a ghost town (the latter two filmed in California’s Red Rock Canyon) — lack the formal purity of those in The Naked Spur. As a result, Man of the West veers much closer to the grimness of Greek tragedy, its mountains and rock formations often suggesting the silent witness of an ancient amphitheater. (The connection isn’t accidental; another of Mann’s late interviews is peppered with references to Oedipus Rex and Antigone, and one of his best early westerns is entitled The Furies.)

The hero, Link (Gary Cooper), is headed for Fort Worth to find a schoolteacher for his remote town, but the train is held up by a gang of thieves, stranding him with a card sharp (Arthur O’Connell) and saloon singer (Julie London). The three go to an abandoned farmhouse, where it emerges that Link used to be a member of the gang, which is led by his half-mad uncle, Dock (Lee J. Cobb); Dock raised him until he ran away in disgust and started a new life. A “link” between the civilization ironically represented by the card sharp and the singer (as well as his offscreen family) and the lawlessness of the gang, he’s welcomed by Dock like a prodigal son returning to the fold and has to play along to keep his two companions alive.

Scripted by Reginald Rose — a TV dramatist of the 50s second in prominence only to Paddy Chayefsky; his best-known work is probably 12 Angry Men — Man of the West is shot in CinemaScope, yet it’s initially hampered by the shallow dramatic space associated with television. This effect is made worse by the casting, which pairs the stagiest of stage actors (Cobb) with the most cinematic of movie actors (Cooper, at 57 only three years from retirement). But Mann is canny enough to turn these limitations to his advantage whenever he can, offering sly notations about Link’s physical discomfort on the train and using a long, tense scene inside the farmhouse to create claustrophobia before sending the characters outdoors for virtually the remainder of the picture. Once again, the hero is a dialectical contradiction, both regressing toward an unbearable past and making an anguished effort to break free from it — the struggle ultimately engendering hatred, violence, pain, and humiliation, and revealing boundless evil.

Classical tragedy is evoked in both these westerns as all of the characters apart from the hero and heroine are gradually killed off. In The Naked Spur, three white men and several Blackfoot Indians die. In Man of the West, the entire gang and one captive are killed, and the penultimate shoot-out in the ghost town is an appropriately eerie split-level confrontation between two wounded, supine men — one stretched out on a porch at screen left, the other stretched out underneath the porch at screen right, as if he were already buried. It’s a key example of the way that landscape and architecture, people and settings, painting and drama, image and idea, classicism and modernism all merge on Mann’s monumental canvases.

Postscript: from a review of Road to Perdition published a week later:

A good counterexample is provided by the two Anthony Mann westerns I wrote about last week. Both incorporate some notion of an avenging hero resorting to violence, though not at all stoically, and both heroes’ loss of emotional control shows their vulnerability, not their power. James Stewart actually bursts into tears in the final scene of The Naked Spur (1953), and Gary Cooper in Man of the West (1958) comes close to doing the same when he punishes an outlaw who forced Julie London at knifepoint to strip by tearing off the man’s clothes. In both cases the impulse toward revenge is clearly and honestly marked as a form of regression toward childhood or more recent traumas, not as any sort of catharsis or adult achievement of justice. Perhaps if Sam Mendes looks for scripts worthy of Anthony Mann, we may get something better than double standards and Oscar bait.