From the Chicago Reader (May 10, 2002). — J.R.

Cinema Without Borders: Films by Joris Ivens

A word of advice to film artists who want to get ahead: don’t move around too much. Film history often gets subsumed under national film history, so filmmakers who keep moving risk getting lost. And stay out of politics, since getting into them invariably puts you on either the winning or the losing side. If you’re on the losing side, many national film histories will write you out entirely; if you’re on the winning side, chances are your film will date faster than last week’s newspaper.

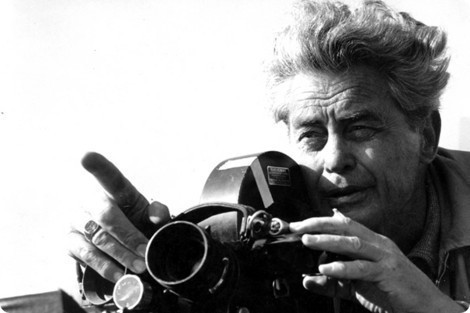

These somber reflections are prompted by what I’ve been able to piece together about the extraordinary career of the Dutch-born leftist documentary and experimental filmmaker Joris Ivens (1898-1989) — who lived in so many places, did so many things, and made so many films he’s come dangerously close to being shut out of history. From the vantage point of America in 2002, I suppose he’d have to be assigned to the losing side, as mainly a mouthpiece for Marxist party lines from the 30s onward, though that would grossly oversimplify his career. Some of the causes he devoted part of his life to, including Stalinist Russia and Maoist China, are now discredited, with good reason, but that doesn’t mean the films he made on their behalf can simply be dismissed or are without interest. He understandably came to regret aspects of How Yukong Moved the Mountains — especially the degree to which his and Marceline Loridan’s direction was directed, so that it concealed as well as revealed — yet I’ve seen few other documentaries that taught me as much about everyday life in China during the 70s.

I have to confess that my acquaintance with Ivens’s work has been spotty, and it remains so, even though I recently crammed in several videos; 16 of his films will be showing in brand-new prints at the Gene Siskel Film Center over the next three weeks, part of a traveling show that started in New York and will end in Vancouver. One Ivens film — his last, A Tale of the Wind (1988) — easily made my list of the 15 best films of the 80s, but I’ve seen only a few other works, and at such scattered intervals that I scarcely know how to put the pieces together. It hasn’t helped that many of his major works in the Film Center series weren’t available for preview, that most of those that were weren’t subtitled (though all the publicly screened prints will be), and that some major works aren’t even included in this retrospective — none of which is surprising given the dimensions of his oeuvre.

You won’t find an entry for Ivens in the long-out-of-print Cinema: A Critical Dictionary (1980), an invaluable collection edited by Richard Roud that sums up what American, English, and French film critics were doing in the 60s and 70s better than any other comparable compilation that comes to mind. But you can find a detailed entry in World Film Directors (1987), edited by John Wakeman and still in print. The life it outlines is staggering — making a Marxist globe-trotter like John Reed (1887-1920), who admittedly lived only about a third as long, seem like a couch potato.

Here’s a man whose grandfather introduced the daguerreotype in Holland and whose father ran a chain of stores selling cameras and photographic equipment, a man who made his first film (The Wigwam, which still survives) when he was 13. A student of economics and photochemistry and a passionate trade-union activist, he fought in World War I, helped found and run the Dutch Film League (which brought such filmmakers as Rene Clair, Jean Vigo, Luis Bunuel, and V.I. Pudovkin to Amsterdam), and experimented with subjective camera techniques. He made poetic shorts about a Rotterdam railway bridge and the rain in Amsterdam as well as major, lyrical documentaries about industrial labor and union struggles. He experimented with fiction (which played a role in his last film) and got invited by Pudovkin to the Soviet Union (where he crashed at Sergei Eisenstein’s flat in Moscow, met Alexander Dovzhenko in Kiev and other major filmmakers in Leningrad, and soon afterward became the first foreign director to work in Russia). He hid from the police in Belgium while making a film about coal miners (Borinage, 1934), then returned to Holland to make his justly celebrated New Earth (1936).

In 1936 he also went to the U.S., then he and John Dos Passos went to Spain to make a film about the Spanish civil war. Dos Passos isn’t credited on the film, The Spanish Earth; Ernest Hemingway wrote and read the narration (another version exists with Orson Welles reading the same narration). Then he went on to China to join the Kuomintang forces and make The 400 Million (1938). He returned to North America for seven years of filmmaking, working with, among others, Pare Lorentz and the U.S. Film Service (Power and the Land, 1940), Lewis Milestone (Our Russian Front, 1941), Shell Oil (Oil for Aladdin’s Lamp, 1942), John Grierson (Action Stations!, 1943), and William Wellman (serving as adviser on The Story of GI Joe, 1945). (After being blacklisted in 1951 he never returned to the U.S.) He went to Australia as film commissioner for the Dutch East Indies while they were occupied by Japan, but resigned his post in the mid-40s to work for the Indonesian colony in exile, which cost him his Dutch citizenship but yielded Indonesia Calling (1946). From there he went to Eastern Europe, making films in Czechoslovakia, Poland, and East Germany (where Paul Robeson, Bertolt Brecht, Dmitry Shostakovich, and 32 cinematographers from across the world were among his collaborators on the 1954 Song of the Rivers, which focused on workers’ movements along the Volga, Mississippi, Ganges, Nile, Amazon, and Yangtze). He finally settled in Paris, his home base for the remainder of his life. There he made a poetic film about the Seine, with commentary by Jacques Prevert, The Seine Meets Paris (1957).

In 1958 he returned to China to make a couple more films. He made a TV documentary about natural gas in Italy in 1959 and a film in Mali in 1960, then spent a few years teaching and making films in Cuba and Chile (including …A Valparaiso, with commentary by Chris Marker). In the mid-60s he made poetic films in France and Holland and took the first of many trips to Vietnam, where he made several films with and for the North Vietnamese, the best known of which is The 17th Parallel (1968). By this time he was working and living with Marceline Loridan, a Jewish concentration-camp survivor who was 30 years younger than himself; she’d appeared in Jean Rouch’s Chronicle of a Summer and remained Ivens’s key collaborator for the rest of his life.

In the early 70s the two went to China to make, among other films, the 12-hour, 12-part How Yukong Moved the Mountains (omitted from the Film Center series), portions of which I saw in the mid-70s. About a decade later, when Ivens was pushing 90, came the masterful and mind-boggling A Tale of the Wind, a documentary full of magic and fantasy that beautifully encapsulates the career that preceded it. (I spoke with Loridan shortly after this film’s premiere at the Rotterdam film festival and compared it to Jean Cocteau’s Testament of Orpheus. She said the problem with that formula was that it left out Eurydice. Other evidence also suggests that the film was probably more hers than his, even though his life and work are at the center of it.) If you decide to see only one film in the Film Center series, you might want to make it this one, playing on Friday, May 24.

A brilliant editor with a fine sense of light and texture, Ivens has to be understood first as a filmmaker as relevant to experimental cinema as he is to documentary filmmaking — a distinction we’re much likelier to make today than he was, especially during the earlier phases of his career. This becomes easy to grasp once one associates him with the “city symphony” films that dominated late silent cinema — a body of work by various directors that includes everything from The Man With the Movie Camera and Berlin: Symphony of a City to such Hollywood masterpieces as Sunrise, The Crowd, and Lonesome.

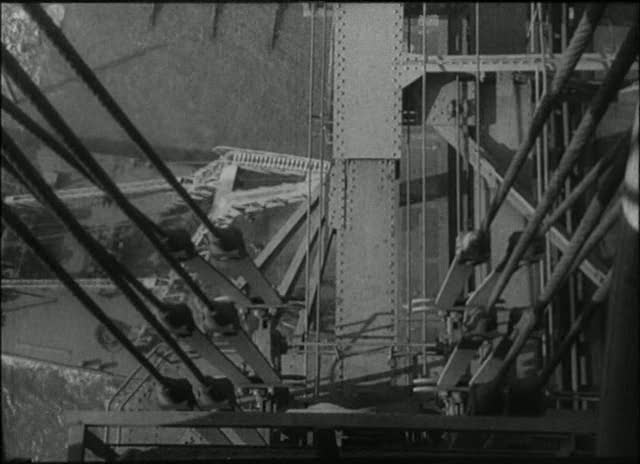

The three earliest short films by Ivens being shown at the Film Center — The Bridge (1928), Rain (1929), and Philips Radio (which is sometimes called Industrial Symphony, 1931) — clearly belong in this category. That the latter — commissioned by the Philips factory, and the first artistic sound film made in Holland — both embraces and attacks the industrial processes it shows, as the University of Chicago’s Tom Gunning cogently argues in the series catalog, suggests that Ivens’s political and aesthetic impulses weren’t always in sync with each other. Gunning describes “an intense ambivalence,” meaning that “Ivens’ camera does portray a dehumanizing system which contrasts completely with the physically bonding labor shown in Zuiderzee [a silent film Ivens made in 1930]….However, Industrial Symphony also seems to participate in this technology, to celebrate it, to be attuned to it, to glide with the machines, to pulse with their rhythm, especially in relation to the music on the soundtrack.”

Ironically, this ambivalence, which is also apparent in many of Ivens’s later films, may have yielded the best “industrials” ever made — not all of which were commissioned by the industries involved (even if one includes countries, bureaucracies, and political groups in this loose category). The pleasures of viewing harmony and dissonance, continuity and discontinuity, peace and struggle are both aesthetic and political; whether these aesthetic and political pleasures mesh or diverge, harmonize or clash, is an almost constant issue in Ivens’s work.

Seeing these issues posed again and again in so many different contexts, we do more than sample different kinds of propaganda. We’re also fooling ourselves if we view Ivens as a political propagandist and Steven Spielberg, Oliver Stone, and George Lucas as apolitical entertainers — and we shouldn’t assume that his original audiences didn’t know what they were watching. The sheer datedness of Ivens’s industrials is something to treasure, not least of all because it forecasts what many of our contemporary favorites will look like several decades from now — minus, perhaps, some of the beauty and excitement.