From the Chicago Reader (April 19, 2002). — J.R.

Time Out

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Laurent Cantet

Written by Robin Campillo and Cantet

With Aurelien Recoing, Karin Viard, Serge Livrozet, Jean-Pierre Mangeot, Monique Mangeot, Nicolas Kalsch, Marie Cantet, Felix Cantet, and Maxime Sassier.

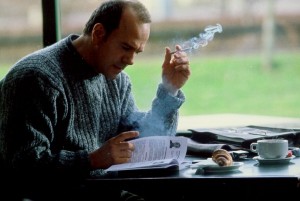

My French-English dictionary defines l’emploi du temps — the term used as the French title of Laurent Cantet’s remarkable feature Time Out — as the “timetable (of work), allotment of time.” Neither translation makes for a catchy film title, so it’s easy to understand why “time out” was selected. It also seems a fairly apt description of the spooky shadow existence of the film’s bland yet mysterious and compelling hero, Vincent Renault (Aurelien Recoing). A financial consultant fired weeks or months previously, he’s afraid to tell his family and friends the news. After a former work associate starts to wonder why he hasn’t told his wife, Muriel (Karin Viard), he invents a new job with the United Nations that obliges him to spend time in Switzerland, then gets his father and some friends from high school to invest in his imaginary activities. All the while he remains on the margins, spending much of his time in a hotel lobby, sleeping in his car in the hotel’s parking lot, eating in convenience stores, and driving aimlessly around the countryside near Grenoble and the French-Swiss border.

Nevertheless, a subtle yet crucial point gets obscured in the English title: that the life Vincent’s living could almost as accurately be called “time in” — the film’s two key recurring images are of Vincent standing outside a building looking in and his view while sitting inside his car looking out. At least by implication, the difference between his fictional work and the real work that preceded it may not be as great as we initially assume. That we never catch even a glimpse of Vincent performing his real work in his real job is telling, because we have every reason to believe that he did that work as sincerely as he’s doing his fictional work. Wandering into a UN building in Geneva and eavesdropping on a board meeting as he drifts down a corridor, he finds a way to imitate the meeting’s abstract patter when he sets up his imaginary projects. So we’re left to wonder, if imitating real life is what he’s doing now, what was he doing before?

This point is only underscored when, relatively late in the film, we hear him describe how and why he lost his job, and we realize that he had inexplicably fallen in love with his own drift, which he experiences basically by driving. (Throughout the film the recurring point-of-view shots from behind the windshield of his moving car reflect his shifting states of mind, whether easygoing or turbulent.) Like the hero of Walker Percy’s The Moviegoer, Vincent can’t be said to have a life in the usual sense; more precisely, he inhabits one.

Some of my colleagues have cited other existential literary models, the most significant being Nathaniel Hawthorne’s “Wakefield” and Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener.” The title hero of the Hawthorne story leaves his wife and home in London, intending to stay away for a few days at the most, but he moves into another flat a block away and remains there for 20 years, a voyeur watching his own previous life, until one day he returns as if nothing has happened. Melville’s title hero is even stranger — a law copyist or “scrivener” on Wall Street who firmly and enigmatically chooses to do nothing: “I would prefer not to” is his recurring refrain, a decision he clings to until he dies.

After describing the plot of “Wakefield” in an essay about Hawthorne Jorge Luis Borges noted, “In that brief and ominous parable, which dates from 1835, we have already entered the world of Herman Melville, of Kafka — a world of enigmatic punishments and indecipherable sins. You may say that there is nothing strange about that, since Kafka’s world is Judaism, and Hawthorne’s, the wrath and punishments of the Old Testament. That is a just observation, but it applies only to ethics, and the horrible story of Wakefield and many stories by Kafka are united not only by a common ethic but also by a common rhetoric. For example, the protagonist’s profound triviality, which contrasts with the magnitude of his perdition and delivers him, even more helpless, to the Furies.” (He goes on to note, “‘Wakefield’ prefigures Franz Kafka, but Kafka modifies and refines the reading of ‘Wakefield.’ The debt is mutual; a great writer creates his own precursors.”)

What Vincent has in common with both Wakefield and Bartleby is not only triviality but a haunting blankness that appears to make him as much an enigma to himself as he is to others, including the audience. Like a carefully polished mirror, Time Out seems designed to show us the strangeness of an everyday life we all inhabit in some way, thrown into relief by a man who’s stepped only a little bit outside of it.

Time Out was inspired by rather than based on a story that received a lot of press in France and was drastically more melodramatic than the one Cantet chooses to tell. (For a book-length account published in English, see Emmanuel Carrere’s The Adversary: A True Story of Monstrous Deception.) Jean-Claude Romand spent 18 years pretending to be a doctor working for the World Health Organization, successfully milking his family and friends for funds, and when his fraud was uncovered in 1993 he murdered his wife, two children, parents, and the family dog, then set fire to their home, hoping to kill himself. (Ironically, he was rescued, and is currently serving a life sentence in prison.) It’s easy to imagine an American movie incorporating all the latter details, given the popular delusion in our culture that violence solves problems (dramaturgically, politically, metaphysically, spiritually) and even offers some sort of enlightenment. But Cantet has something entirely different in mind. He’s described his filmmaking models as an improbable blend of the melodramas of Douglas Sirk and Italian neorealism, and Canadian film critic Mark Peranson has provocatively compared Time Out to Alfred Hitchcock, suggesting that a particular line from North by Northwest could serve as the film’s epigraph: “In the world of advertising, there’s no such thing as a lie. There’s only the expedient exaggeration.”

The same thing might be said of movie acting — and the expedient exaggerations in this case are at times so subtly delivered we don’t recognize them as such. Recoing, a stage actor, is so good at this kind of notation that when he shows Vincent trying hard to look as if he “belongs” to a group of executives entering a building, it’s hard to say how he conveys that impression. (Something comparable occurs in the final scene — which in some ways functions as a key to the entire film — when the camera moves closer and closer to Vincent’s eyes while he assures someone that he’s not afraid.) The beauty of the film’s score, by the talented Jocelyn Pook (whose work has been used effectively in English experimental videos and Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut), is related to a similarly unforced way of producing indelible effects — offering an object lesson to Philip Glass and his grandstanding, less cinematically conceived film scores.

It’s worth adding that all of the actors in this film apart from Recoing and Viard are nonprofessionals (one of the characteristics we associate with Italian neorealism). Vincent’s two youngest children, a girl and a boy, are played by Cantet’s own kids, and Vincent’s parents are played by a real couple. Furthermore, Recoing and Viard’s acting meshes seamlessly with that of the amateurs; all of the characters reveal things about themselves through body language, and the climactic scene when Vincent confronts his family after they discover his deception is a remarkable series of acute emotional observations. Cantet’s previous feature, Human Resources (1999), showed how well he understands family dynamics, particularly the tensions that can exist between a father and son.

Julien (Nicolas Kalsch), Vincent’s adolescent older son, is clearly the child he’s most attached to; not coincidentally, he’s also the one who’s chosen to retreat as much as possible from the family. When Vincent responds to Julien’s distance by handing him money, we feel that he’s replicating his relationship with his own father — just as when Julien refuses to come to dinner after he discovers the truth he’s anticipating Vincent’s refusal to face his own father. And when we discover that Vincent has given Julien a cell phone — the film’s pivotal emblem of noncommunication masquerading as intimacy — Vincent’s deception posing as candor is given an extra charge. (At least Vincent uses his phone mainly while in or near his car. People who use cell phones while walking down crowded streets are arguably denying the existence of fellow pedestrians and the fact they’re sharing space with them.)

The unforced ordinariness of Vincent’s family is echoed in most of the friends and former associates we see. This makes the charismatic performance of Serge Livrozet as Jean-Michel, who functions in the film almost as a choral figure, all the more striking — as if one of the best French character actors suddenly stumbled onto alien turf. An amiable thief and smuggler, Jean-Michel effectively adopts Vincent, hiring him to help with his smuggling after he sees him dozing in a hotel lobby and correctly intuits that he needs work. Jean-Michel alleviates the drabness of the film’s human landscape with his charisma and warmth — something accomplished in a different way by Maxime Sassier as Nono, a trusting childhood friend of Vincent’s — and proves to be as welcome to us as he is to Vincent. Virtually a deus ex machina, he turns up at the 11th hour to make an honest crook out of Vincent, inviting us to savor the paradox. (According to Cantet, Livrozet himself has a background as a criminal, and his strong Marseilles accent signifies “gangster” for French spectators.)

Ever since Time Out was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice film festival last August, it’s had a big impact, in this country as well as elsewhere. The Music Box has booked it for three weeks, one indication of the chord it has been striking with audiences by showing a kind of spiritual malaise that’s instantly recognizable.

To prove that Vincent isn’t a villain or someone we can feel estranged from, Cantet makes sure we know that Vincent’s love for his wife, his family, and at least one of his old friends is sincere. We also see the degree to which he and his family and friends are complicitous in his lying; Muriel proves to be even more nonconfrontational than he is, especially after the truth finally emerges, making her, at least by default, one of his two “partners in crime” (as the film’s press book aptly puts it). His father and friends are also implicated insofar as their expectations and financial support encourage his fantasies. This film, like Charlie Chaplin’s neglected Monsieur Verdoux, may be one of the best movies ever made about business, and like Chaplin’s masterpiece it approaches the topic less through the activity itself than through the psychological positioning it entails.

The marvel of the film is that, like its hero and his literary cousins, it’s simple to the point of being insipid, yet what it winds up saying proves to be bottomless — a conclusion one might arrive at only long after seeing it. For 132 minutes, we follow this dull company man without a company as he drives around, talking on his cell phone to everyone he cares about, spinning inventions about what he’s doing. Cantet seduces us not only into understanding but sharing his dilemma. He wants us to be appalled yet sympathetic, and he succeeds largely because he’s found a way to make his story seem paradoxically monotonous and gripping, familiar and peculiar, all at the same time.