From the Chicago Reader (June 15, 2001). — J.R.

Signs & Wonders

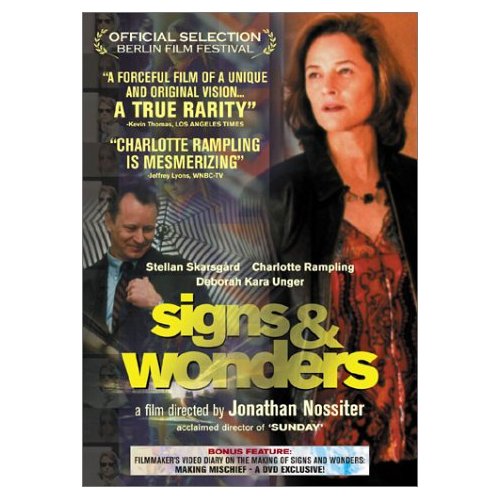

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Jonathan Nossiter

Written by James Lasdun and Nossiter

With Stellan Skarsgard, Charlotte Rampling, Deborah Kara Unger, Dimitris Katalifos, Ashley Remy, and Michael Cook.

+

The Fourth Dimension

Rating *** A must see

Directed, written, and narrated by Trinh T. Minh-ha.

Broadly speaking, Signs & Wonders, an ambitious thriller set in contemporary Athens, and The Fourth Dimension, a documentary about Japan, derive most of their strengths from being meditations by American tourists. Signs & Wonders, running this week at Facets Multimedia Center, is a 35-millimeter feature shot on digital video, and it’s directed by Jonathan Nossiter, a quirky and talented son of a journalist who grew up in France, England, Italy, Greece, and India and has made only one previous narrative feature, Sunday (1997). Nossiter wrote both films with James Lasdun, a Londoner now based in the U.S. who also wrote the story on which Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1998 Besieged was based.

It’s a gorgeous mess of a movie, brimming with provocative ideas about the state of the planet, multinational corporations, political amnesia, American idealism, and some of the monstrous ways love can turn sour, and demonstrating how these ideas can converge and inform one another. Signs & Wonders tries for all sorts of things — practically promises us the moon — though for reasons that still puzzle me, it abjectly capsizes into confusion and pretension during its last 20 or so minutes, around the same time it leaves Athens for the Greek countryside. Still, it has more to say than any other new American picture I’ve seen so far this year.

The Fourth Dimension, a digital video showing on Friday at Columbia College, is by Trinh T. Minh-ha — a poet, essayist, musician, composer, and filmmaker who was born in Hanoi and educated in Paris and has been teaching for years in and around San Francisco, most recently at Berkeley. She has eight books and five films to her credit; four of the films are of feature length, and all but one are documentaries. The first two, Reassemblage and Naked Spaces–Living Is Round, were shot in Africa; the third and fifth, Surname Viet Given Name Nam and A Tale of Love (her only narrative feature), were shot in California; and the fourth, Shoot for the Contents, was shot in China.

The Fourth Dimension, whose subjects range from Miyajima to No theater, is more visually distinctive and pleasing to the eye than any of Trinh’s other films, possibly because she shot it herself and possibly because she makes her discovery of the benefits of digital part of her subject. (“The image, coming alive in time as it frames time, is there where the actual and virtual meet” is her theoretical take on the matter.) She’s especially good with color and with changing the shapes of her images, so that her opening shots of fog on a highway appear inside a square floating up and down and then left to right across the screen, before turning into a thin vertical strip and then a horizontal one. Mutable shapes of this kind evoke the apparent lack of gravity often found in the writing in Japanese TV commercials; they spread out in all directions and suggest that the essay to come will be both ungrounded and drifting in various ways, a more mixed blessing.

About three quarters of the way through the video, Trinh briefly discusses Japan’s “new image” as a “corporate society,” calling it “a global economic power struggling today to reorient itself, to turn toward Asia without turning its back on the West.” But the remainder of the video views Japan in relative isolation from the rest of the world, seeing it principally in terms of public spectacle and landscapes glimpsed from bullet trains. This makes it seem somewhat old-fashioned next to Nossiter’s feature, despite a very modernist score (“The Construction of Ruins with Greg Goodman, unprepared piano and unwanted objects, together with Shoko Hikage, voice and bass koto”) and Trinh’s style of narration, which at times comes across as disconnected aphorisms. (The book of Trinh’s that The Fourth Dimension most resembles may be a slim volume of mainly French poetry, en minescules.)

***

Nossiter defines Athens principally as a part of the anonymous mall sprawl that multinationals are establishing everywhere within their greedy grasp, making the city an easily recognized horror. I happened to see Signs & Wonders for the first time at a gigantic mall in downtown Buenos Aires, the site of a former food market and a dead ringer for the largest mall in Nossiter’s movie; both, for instance, have a Ferris wheel on an upper level.

Nossiter shoots such environments in a manner that feels oddly surreptitous — as if he were stealing furtive glimpses of the characters in public and private places alike. Our first glimpses of both Charlotte Rampling and Stellan Skarsgard, the two leads, are even made to seem accidental, as if the camera caught them in the street quite by chance. This makes Nossiter’s use of digital video an unfolding discovery, just as Trinh’s use of it is — though his decision to shoot on video was made at the last minute, reportedly for aesthetic rather than economic reasons, in particular his intense dislike of the look yielded by Kodak film. A stylistic corollary to this is the fascinating way he mixes a Satie piano piece and a Tommy Dorsey dance tune into his sound track, heard at varying volumes and creating a kind of aural discontinuity comparable to what he achieved in portions of Sunday. (The piano piece can also be heard in Orson Welles’s 1968 The Immortal Story, which may be why Nossiter, a fanatical Welles enthusiast, used it.)

Alec Fenton (Skarsgard), the antihero, is an Americanized commodities trader who’s been living in Athens with his Greek-American wife Marjorie (Rampling, in what may be her most finely shaded performance) and their two kids. From the somewhat scattershot narrative — evoking at times a Nicolas Roeg film and Richard Lester’s Petulia — we gradually piece together that Alec has twice left Marjorie for Katherine (Deborah Kara Unger), an American coworker, but has recently become obsessed with rejoining his former wife. Marjorie works at the U.S. embassy and has begun a serious affair with a Greek political activist named Andreas (Dimitris Katalifos), who plotted against the military dictatorship of 1967-’74 and is now trying to establish a museum to commemorate the resistance movement.

Andreas remarks at one point that if Americans give money, it’s because they feel guilty about something; knowing that the U.S. helped prop up Greece’s military dictatorship, he finds it easy to approach Americans for corporate donations. Combine this wry observation with Alec’s inability to learn Greek and his self-important and myopic manner of taking the blame for his adultery without giving up the marriage he’s destroyed and you seemingly have the makings of an anti-American polemic. But Nossiter has cogently refuted any such intent in interviews: “The French seem very happy to regard it as anti-American because it makes the French feel better,” he’s said, noting that “the evil is not America” but McDonald’s and multinationals in general. “The film takes a critical look at the Americanization of other parts of the world,” he adds, “but the complicity is mutual.”

Lasdun has said that the story grew out of the sense of displacement felt by both him and Nossiter — an Englishman living in the States and an American who grew up in Europe. He also notes that two phrases from U.S. history –” the pursuit of happiness” and “manifest destiny” — became crucial reference points in creating Alec’s character, an innocent for whom happiness amounts to a religious imperative and “the external world becomes supercharged with latent significance” (which also accounts for the film’s title). Lasdun pointedly calls Alec “a monster, but also a figure of genuine decency,” which gives one some notion of the multiple ambiguities involved. (The ambience of a Graham Greene novel may be as pertinent here as a Nicolas Roeg film or Petulia.) Though the story is told mainly from Alec’s viewpoint, the film makes it increasingly difficult to identify with him as an authoritative witness, and we find ourselves depending more and more on other characters.

This kind of divided consciousness makes much of the film vibrant and suggestive, but like the contemporary global marketplace, with all its ambiguities, it ultimately saddles the filmmakers with more than they or we can possibly process. As the plot becomes progressively overloaded with subplots and mysteries, we also get a panoply of cross-references and meanings, ranging from Alice in Wonderland (in Greek translation no less) to the allegorical significance of Katherine becoming pregnant by Alec and deciding to have an abortion. All of this is more than any film could handle — I couldn’t even piece together all of the plot — but at least the movie crash-lands in high style.