From the Chicago Reader (April 7, 2000). — J.R.

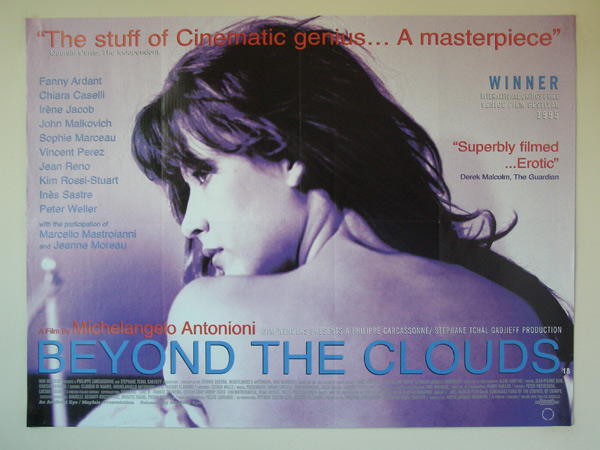

Beyond the Clouds

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Michelangelo Antonioni (with Wim Wenders)

Written by Antonioni, Tonino Guerra, and Wenders

With John Malkovich, Ines Sastre, Kim Rossi-Stuart, Sophie Marceau, Chiara Caselli, Peter Weller, Fanny Ardant, Jean Reno, Jeanne Moreau, Marcello Mastroianni, Irene Jacob, and Vincent Perez.

Chicago has had a plethora of film festivals lately — Women in the Director’s Chair, Polish Movie Springtime, Chicago Latino Film Festival, the Asian American Showcase. This is probably good for filmmakers who want their work shown, but I’m not sure it’s a boon for moviegoers. For one thing, the screening of so many films at once makes it easy for good work to get lost. Billions of dollars are now spent annually making and promoting a few dozen movies — most of them dogs — that the media obligingly make visible and label important, and everything else is consigned to relative oblivion. The most any obscure film can hope for — good or bad, major or minor — is to compete with all the other obscure films. This is tantamount to tripling the number of passengers in steerage without increasing the provisions: more people get to travel, but everyone gets brutalized in the process.

For another thing, the festivals seem based on the assumption that tribal notions determine which films should be shown and seen together. Such notions have little to do with my own interest in seeing movies, and they sometimes force festival organizers to shove square pegs through round holes. Dance Me to My Song, Post Concussion, and Bugaboo are all by, with, and about people playing fictionalized versions of themselves: a woman with spastic cerebral palsy who wants to have a sex life, a former management consultant developing a new life while recovering from a serious head injury, and an engineer trying to overcome boredom in Silicon Valley. Theoretically, each of these films could have appeared in any of several recent festivals. But because the cerebral palsy victim (the lead actor and cowriter) is female, Dance Me to My Song wound up in Women in the Director’s Chair, even though the director is male. Post Concussion, whose former management consultant is Korean-American, and Bugaboo, whose engineer is Indian, wound up in the Asian American Showcase.

All of which is pretty confusing, especially since the former management consultant’s Korean-American background seems to have no bearing whatsoever on the story in Post Concussion. However, the press notes for Bugaboo state that the film “has been made by, for, and about Silicon Valley engineers. It should also have a wider appeal among expatriate Indians and Indians in the urban centers of India” — two more categories I don’t belong to. It makes me feel vaguely guilty for not searching out festivals of films by, for, and about male Jewish-American film critics so I can explore my own issues.

Dance Me to My Song was made in 1998; I presume it took two years to reach Chicago because it’s Australian and it centers on someone with spastic cerebral palsy. So why did it take twice as long for the last feature of Michelangelo Antonioni, playing this week at the Music Box, to make it here? After all, Beyond the Clouds — a sketch film containing four stories by Antonioni — is mainly about sex, is full of attractive and well-known stars, and was a box-office smash when it was released in Europe in 1996, reportedly doing better in Italy than any previous Antonioni film.

I can’t think of a reason for this absurd delay, apart from some version of the usual American art-house jitters. But maybe it’s because not once in the past four years did anybody think of organizing a festival of films in Chicago that all happen to be beautiful. I suppose the very idea sounds indecent, hokey, and scandalously out-of-date–and so, I’m afraid, will Beyond the Clouds, a movie guaranteed to embarrass and intimidate and enthrall at least some of us for precisely the same reasons. A monument of sorts to political incorrectness and outdatedness, it stands at the very end of an Italian tradition in cinema represented by Antonioni, Fellini, Pasolini, Rossellini, and Visconti — much as Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, according to film historian Tom Gunning, stands at the very end of what might be called the Viennese school of Lang, Preminger, Sternberg, Stroheim, and Wilder.

There are a lot of beautiful things in Beyond the Clouds: the style, the settings, the bodies of young men and women — many of them beautiful in the vaguely blank way that models are. The movie isn’t so much sexy as erotic, and as with the rest of Antonioni, it’s every bit as involved with the erotics of place as with the erotics of flesh; the two might even be said to become intertwined, and Antonioni’s style, his mise en scene, might be described in part as the process of that intertwining, carried out with camera, actors, and locations. Sometimes colors and textures play a central role in this interplay; when an American man (Peter Weller) in the third episode visits his Italian mistress (Chiara Caselli) for lovemaking on two occasions at her Paris flat, her red silk blouse in the first visit and the red in her pillows, sheets, and bedspread in the second make a stronger impression than her skin. And the rhyme effects created in the same story between one flat filled with objects and another flat stripped of furniture create a comparable kind of visual poetry — one that eventually brings two strangers together, Weller’s neglected wife (Fanny Ardant) and a recently abandoned husband (Jean Reno).

“Beauty nowadays is largely out of fashion,” writes Gilberto Perez in his invaluable recent book The Material Ghost: Films and Their Medium, which also contains one of the best appreciations of Antonioni. “Postmodernists mostly disown it. As a quality men see in women (‘Beauty is pleasure regarded as the quality of a thing,’ said Santayana), feminists largely discountenance it. The Thatcherite aesthetician Roger Scruton thinks it too imprecise a notion for meaningful consideration; but an aesthetician who cannot talk about beauty had better find another line of work. On the left beauty is suspect both of being elitist, the plaything of a privileged few, and of being a whore seductively selling the ideology of the ruling class. In the puritanism of today, a puritanism on the right and on the left, beauty is to be approached with the protective crucifix of (Right or Left) political correctness.”

Politically correct viewers may also find it indecent that Antonioni made Beyond the Clouds when he was 83 — a dirty old man by our usual puritanical standards. It was the same year that he received a lifetime achievement award at the Oscars and ten years after a stroke that left him partially paralyzed and largely unable to speak. (He hadn’t made a feature since Identification of a Woman in 1982, another highly erotic movie — and one that’s never opened commercially in the U.S., though Facets Multimedia is bringing it out on video this July.) That he was able to make this film was partly due to the patient devotion and persistence of several individuals, including his wife, Enrica (who interpreted his instructions to the actors and crew whenever his gestures, eye movements, and drawings didn’t suffice), and coproducer Stephane Tchalgadjieff (perhaps the most adventurous of all European producers, whose credits include Jacques Rivette’s Out 1, Marguerite Duras’ India Song, Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s Fortini-Cani, and Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably). Antonioni’s age and condition posed problems for the insurers, so Wim Wenders offered his services as a “standby director” and wound up directing and cowriting the prologue, epilogue, and the interludes between the four stories, all of which feature John Malkovich as a roaming filmmaker looking for material. Antonioni kept only two of these segments in the final editing; he and others agreed that using them all would have weighed the film down. He tried to shoot another feature about a year ago in the U.S. but had to quit — making it extremely unlikely that Beyond the Clouds will have a successor.

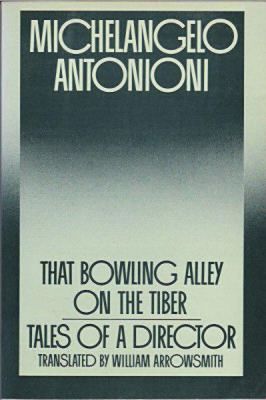

The four stories and the Malkovich monologues are all adapted from a singular collection of stories by Antonioni, That Bowling Alley on the Tiber: Tales of a Director, published in Italian in 1983 and in English three years later. (The film adroitly mixes dialogue in Italian, English, and French.) There are 33 stories or fragments in the book, ranging in length from three sentences to 14 pages. The shortest, a piece of fancy entitled “Antarctic,” reads, “The Antarctic glaciers are moving in our direction at a rate of three millimeters per year. Calculate when they’ll reach us. Anticipate, in a film, what will happen.”

The translator, the late William Arrowsmith, points out in his sensitive preface that these stories and concepts invite the reader into the director’s workshop, though they’re neither notes nor outlines; instead they’re fully composed and selective “narrative nuclei.” “The Event Horizon,” which opens the book, forms the basis for the film’s prologue, and the four stories — appearing in the book in a different sequence — are “Story of a Love Affair That Never Existed,” “The Girl, the Crime…,” “Don’t Try to Find Me,” and “This Body of Filth.” All four are about sexual encounters between a man and a woman who are strangers — though other characters also figure in “Don’t Try to Find Me,” the story that’s been changed the most — and the encounters alternate between failed and successful. The first and last couples fail to get it on; the second and third succeed gloriously. The first two episodes also take place on opposite sides of northern Italy — Ferrara in the east and Portofino on the west coast; and the last two take place on opposite sides of France — Paris in the north and Aix-en-Provence in the south.

There’s only one brief segment that can’t be traced back to a passage in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber — the brief sequence with Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni that introduces the final story. If I’m not mistaken, this is one of the few segments directed by Wenders, and the topic is a meditation on the implications of Wenders’s involvement in the film — a self-reflexive interlude inspired by the fact that Wenders is trying to imitate Antonioni’s style in the portions of the film he directs.

Mastroianni and Moreau were the stars of Antonioni’s 1961 feature La notte — the middle film in the trilogy that began with L’avventura and ended with Eclipse — so their presence constitutes a reference to his earlier work. On a mountaintop, Moreau approaches Mastroianni, who’s working on a painting that’s a pastiche of one of Cezanne’s most famous canvases of Mont Sainte-Victoire, and wonders aloud, in French, “why our society needs all these copies of things. I’m speaking not only of copies of paintings, but copies of everything.” Mastroianni winds up telling her that the desire to repeat the precise gesture of a great artist is what mainly motivates him.

An overlapping dissolve from Mastroianni’s canvas to a reproduction of the Cezanne painting he was emulating brings us to the lobby of a hotel in Aix-en-Provence, where Malkovich is looking at the reproduction and Moreau is seated nearby, reading a book by Doris Lessing. A moment later, seeing Malkovich cross his arms in imitation of the model in another Cezanne reproduction, a portrait of a peasant, she playfully prompts Malkovich’s movements, in English: “No, the other arm, underneath. Tilt your head to the right. A little sadder. That’s it.”

It’s a complex little pirouette on the auteur theory, all the more teasing because one can’t say with certainty who is imitating whom. (As a witty riff on postmodernist imitation, it certainly beats the entirety of The Talented Mr. Ripley.) Wenders may be directing here in a pastiche of Antonioni’s style, but is this scene simply Wenders imitating Antonioni, or Antonioni imitating Wenders imitating Antonioni, or some combination thereof? And what role, if any, does cowriter Tonino Guerra play? If Antonioni is being equated with Cezanne, is this his own immodesty or is it the flattery of Wenders or Guerra?

It’s fortunate that we can’t answer these questions, because any resolution would diminish the meaning — as is generally true of Antonioni’s work. In fact, much of the power of the two Italian portions of the film, both of which register like mysterious fairy tales, lies in their quizzicality — seen in the inscrutable nature of a young man named Sylvano (Kim Rossi-Stuart) in the first and of a young woman who’s never named (Sophie Marceau) in the second. (I’m going to recount both stories, so some readers may want to check out here.)

The young woman in Portofino is followed by Malkovich down a lovely winding street into a seaside clothing store where she works; later on she approaches him in a nearby cafe to inform him that she killed her father, stabbing him a dozen times; and still later, the two of them make love in his hotel room. What’s inscrutable isn’t only her character — why she killed her father, why she tells Malkovich about it, why they make love — but the nature of his subsequent brooding reflections on the encounter as raw material for a future movie, which end with a reference to James Joyce’s “The Dead.” The title of the original story contains an ellipsis (“The Girl, the Crime…”), which is emblematic of Antonioni’s style and method — the three dots are every bit as representative of the episode as “the girl” and “the crime”; in this respect, among others, Antonioni can be seen as an unexpected blood brother of Ernst Lubitsch (who’s evoked in the film’s final sequence).

The inscrutable nature of Sylvano is tied to Ferrara — “It’s a strange story only for those who weren’t natives of this city, like me,” Malkovich notes offscreen; “Story of a Love Affair That Never Existed” is the only one of the four stories in That Bowling Alley on the Tiber whose location is stated by name. (“The Girl, the Crime…” is set in “a small town at the foot of a very green mountain, forming a semicircle around a tiny bay of white boats,” which in the film becomes Portofino; the settings of the two French episodes are less specific.)

Sylvano, a water-pump technician, is driving through Ferrara quite by chance and asks Carmen (Ines Sastre), a schoolteacher on a bike, for advice about a nearby hotel, which she winds up checking into as well. After a brief flirtation in the hotel’s restaurant–he grazes her neck with his lips — they go for a walk under the same arcades where they met, and their mutual attraction is palpable. But when they return to the hotel, he leaves her and goes to his own room. They both spend a sleepless night waiting for something that never happens.

When they meet by chance again a couple of years later, at a screening of Nikita Mikhalkov’s Urga, they’re both living in Ferrara, and they come much closer to having sex. She lets him into her apartment; but when he tries to kiss her she pulls away, and he leaves. Lingering outside, he looks back at her flat, returns, and she lets him in again. There’s a cut to them both nearly undressed on her bed exchanging shy caresses; he moves his hand over her entire body without touching it, then does the same thing with his lips — a scene that paradoxically makes one more acutely aware of the warmth of both their bodies than any conventional coupling would. Finally he pulls away from her, dresses, and leaves. She looks out her bathroom window at him as he walks away, and he looks back. Malkovich says, “He went on being in love with that girl whom he never possessed. Either out of stupid pride, or from folly. That quiet folly of his city.”

Describing Beyond the Clouds as “a lovely farewell work,” Gilberto Perez calls it “a film about desire unattainable not because desire is always anxiously unattainable (as Freud and Lacan and all their followers think) but because desire is finally, serenely unattainable to an old man who knows what he will be missing as the world slips away from him.” This certainly matches the film’s first and last episodes, and I wouldn’t call it irrelevant to the film as a whole. Yet looking back at my two favorite Antonioni features, L’avventura and Eclipse, I note that the first ends with a couple tragically reunited and the second ends with a couple attracted to each other but failing to meet, and it’s hard to determine which ending is sadder. For that matter, I’m not even sure which is more erotically potent or meaningful in Antonioni’s work, postcoital melancholy or unfulfilled sexual desire. There is so much of both, and both are perceived by Antonioni as mysterious and open-ended states of mind and feeling.

Beyond the Clouds, like Identification of a Woman before it, comes closer to pornography in its voyeurism than any of Antonioni’s earlier works, but paradoxically it also winds up finding desire even more erotic when it remains unfulfilled — if only because that leaves more imaginative options open. When Sylvano returns to Carmen’s flat a second time, I wrote in my notebook, “This is why movies were invented.” Like every other Antonioni film, Beyond the Clouds can’t find anything more voluptuous than ending every sentence with either an ellipsis or a question mark.