From the Chicago Reader (January 14, 2000); also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Rosetta

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne

With Emilie Dequenne, Fabrizio Rongione, Anne Yernaux, Olivier Gourmet, and Bernard Marbaix.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

I saw Rosetta three weeks ago, and haven’t recovered from it since. In fact, I didn’t see any film since the Dardennes’, except films for work. It moves me to the heart of my heart, this film about the necessity of life, the impossibility of morality, the soil of human experience. [A teaching colleague] told me that he couldn’t watch it because he thought too much about [Robert Bresson’s] Mouchette, but precisely, it’s at last Mouchette today, our Mouchette, the one we deserve, without any heaven and any transcendence. Her scream, ‘Mama! Y’a d’la boue! Y’a d’la boue!’ [‘Mama! It’s full of mud! It’s full of mud!’] haunts me, I can’t forget it, it’s exactly the despair of being in life without any pathos, any margin, just real life in the immediacy of the impulse. — E-mail from film critic Nicole Brenez

The 80s practically ended with the euphoric takeover of Tiananmen Square by more than a million demonstrators led by students, many with access to fax machines, though a brutal government crackdown followed. And the 90s ended with the disruption of the World Trade Organization’s meeting in Seattle by an extremely diverse coalition formed through E-mail. It wasn’t a throwback to the 60s — we’re living in an era of greater economic disparities, where class is in some ways becoming a more significant distinction than nationality or language — but at least it suggested that people aren’t powerless and sometimes can triumph over the designs of multinational corporations.

Forms of communication are no longer shaped by cold-war prototypes. Products and operations rather than national ideologies have made much of the world kin, and those products and operations function less like the front line of an invading army than like a long highway anyone can travel down — which may make them destroyers of national ideologies.

Even the multinationals are changing. Kentucky Fried Chicken and McDonald’s outlets in Japan aren’t simply or necessarily promoting the American way of life. They sell corn soup at McDonald’s in Tokyo — which means they’re using American decor to sell a Japanese product and thereby promoting the Japanese way of life. Which isn’t to say that way of life hasn’t changed; who’s to say what is the Japanese way of life anymore? Hot cans of corn soup and of Pokka espresso are sold everywhere in Japanese vending machines. Pokka is brewed in American Canyon, California (though if you want to buy it in Chicago you have to go to an Asian supermarket), and the Pokka people can hardly be said to be promoting an Italian way of life.

All of this is a roundabout way of underscoring my point that it’s silly for the mainstream American press to go on assuming that foreign movies are neither relevant to American audiences nor important. Rosetta, a Belgian film that’s starting its second and final week at the Music Box, won the top prize at Cannes, the world’s top film festival, and its 18-year-old lead, Emilie Dequenne, shared the best-actress award. Its story, subject, and heroine are probably more relevant to the lives of most Americans — and have more physical presence and pack a bigger emotional punch — than the story, subject, and characters of most current Hollywood films. Nevertheless, most American critics have refused to give this current American release even a fraction of the attention they lavish on any American movie.

An American friend who recently returned from Europe told me Rosetta has already inspired a new Belgian law known as “Plan Rosetta,” which prohibits employers from paying teenage workers less than the minimum wage (a Belgian news source on the Internet reports this passed on November 12). But the American press hasn’t, to the best of my knowledge, considered this fact worth reporting.

What can we conclude from the passing of this law? One person at a discussion following a preview thought it meant that European moviegoers are more serious than their American counterparts, but I disagree. I think the different impact a movie like Rosetta has in Europe is mainly a consequence of how it’s treated by the press. For instance, Dequenne appeared on the cover of France’s leading rock weekly late last September, but she could never conceivably appear on the cover of Spin or Rolling Stone.

The film’s reputation and therefore its power in Belgium is easy to account for. Local pride at winning the Paume d’or at Cannes gave the movie a high profile — and helped it avoid being swamped by the millions of publicity dollars spent by Hollywood studios to ensure that Belgian moviegoers were more aware of the latest Arnold Schwarzenegger and James Bond shenanigans. In this country there’s practically nothing in the press to prevent it from being swamped by even more millions of publicity dollars.

It’s understandable that American audiences often wind up confusing promotional presence with cultural importance, since promotional presence seems to be the only gauge the mainstream media have for determining cultural importance. It’s meaningless to claim that American audiences “prefer” End of Days or The World Is Not Enough to Rosetta given that most Americans have been bombarded with advertising for those profoundly inconsequential movies but haven’t heard a word about Rosetta. Moreover, the very fact that millions had to be spent advertising End of Days and The World Is Not Enough actually helps demonstrate that the media bias in favor of dumb big-budget entertainment doesn’t suffice to sell it to the masses.

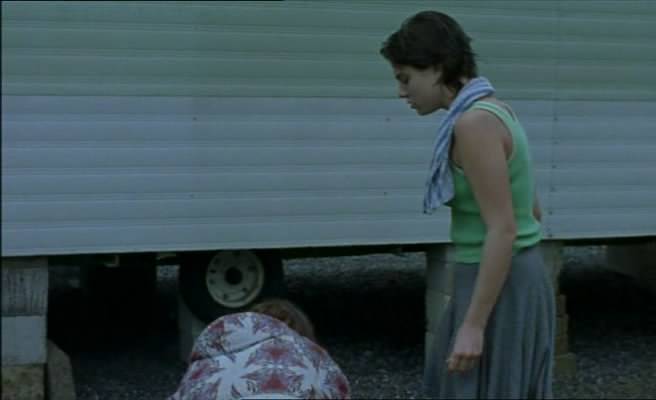

From its opening seconds, Rosetta makes it clear that its heroine is angry — before it tells us who she is or what she’s angry about. Alain Marcoen’s virtuoso handheld camera, which will stay close to her throughout the film, follows as she slams a door, strides through the industrial workplace where she’s just been laid off for obscure reasons, and then assaults her boss when he insists that she leave. After taking the bus back to the trailer park where she lives with her alcoholic mother, Rosetta stops briefly in the woods and methodically takes off her shoes and puts on a pair of boots hidden behind a large rock in a drainpipe. This ritual is repeated throughout the film, marking the transition between her work and her even more solitary home life, where most of her time is spent keeping her mother away from booze and sex (her mother’s principal method of acquiring booze), fishing in a nearby muddy creek, and soothing her stomach pains, usually by warming her belly with a hair dryer.

After Rosetta meets a teenage boy named Riquet (Fabrizio Rongione) who operates a waffle stand and has romantic designs on her, the plot thickens, but not predictably. Riquet finds her work for a brief spell, but she regards him more as a competitor than a friend; when he accidentally falls into the muddy creek trying to help her, she almost lets him drown because she wants his job.

Rosetta is a grim character in a grim set of circumstances, yet the film’s writer-directors, Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne, are so ruthlessly unsentimental, uncynical, and physical in their approach to her life that we experience it viscerally before we get a chance to reflect on its meaning. Toward the end of the film Rosetta has to carry her mother across the trailer park, and it’s extraordinary how much Marcoen’s camera style makes us feel the weight of her body. The physicality of the film as a whole often becomes overwhelming; it’s as if the Dardennes had converted the physical facts of Rosetta’s existence into something resembling a theme-park ride.

To a lesser extent, this was also true of their previous feature, La promesse (1996), which brought the brothers their worldwide reputation. It’s the tale of a 15-year-old boy named Igor who, like Rosetta, lives with a single parent, in this case a slum landlord who rents to recently arrived immigrants, some of them illegal. An illegal immigrant from Burkina Faso with a legal wife and baby son falls from a scaffold while working for the landlord, and as he’s dying, the immigrant asks Igor to take care of his wife and son. Igor agrees, a decision that ultimately leads him to reject his father while coping with the scorn and incomprehension of the immigrant’s widow, who believes her husband is still alive.

Perhaps what’s most distinctive about the Dardenne brothers — middle-aged leftists based in Liege, a city in eastern, French-speaking Belgium, with a background in political videos and TV documentaries — is their utter lack of didacticism about their characters combined with a curiosity about them that gives them a novelistic density, ambiguity, and unpredictability. One comes away with the impression that Igor and Rosetta are both volatile and vibrant works in progress, existential protagonists in the purest sense. The Dardennes also seem to know the working-class locations in and around Liege like the backs of their hands, so their stories almost always seem plausible.

These stories are edgy in part because the Dardennes never seem to know more about their characters than they show. The moments at which La promesse and Rosetta end appear to be precisely the moments at which the filmmakers choose to stop imagining what comes next. Yet it’s fascinating that it’s impossible to guess what Igor will do or say five seconds after La promesse ends, and the same thing is true of Rosetta at the end of Rosetta. Some might consider this a limitation, particularly given the depths of the characterizations found in, for instance, Erich von Stroheim’s Greed. But I regard it as a strength that the Dardennes’ instinct for fiction closely parallels their instinct for documentary and that they refuse to claim more knowledge of their characters than they’re ready to impart. Their work with Dequenne suggests that she operates the same way, with the same tight focus; interviews with the three of them have revealed that they have somewhat different interpretations of portions of the story that were deliberately left in the dark: the identity of Rosetta’s father, the source of her stomach pains, the significance of the final scene.

Nicole Brenez and her colleague aren’t the only critics comparing Rosetta to Bresson’s Mouchette, and the parallels in terms of plot and character are hard to ignore. But there are substantial differences in style and philosophical meaning, and the stories end in drastically different ways. The Catholic context lurking in the background of Bresson’s film and, I strongly suspect, Georges Bernanos’ source novel couldn’t be further from the social coordinates of the Dardennes’ universe, and it’s no slur to say that Mouchette could never have changed the labor laws of France. Moreover, the Dardennes’ rigorous adherence to their heroine’s viewpoint is a world apart from Bresson’s more distanced compassion. Significantly, one comes away from Rosetta with almost no firm physical or emotional recollection of the heroine’s mother (Anne Yernaux) — not because the camera ignores her, but because one feels that the Dardennes, like Rosetta, have given up on her. Mouchette’s invalid mother, who dies over the course of the film, leaves a much stronger impression.

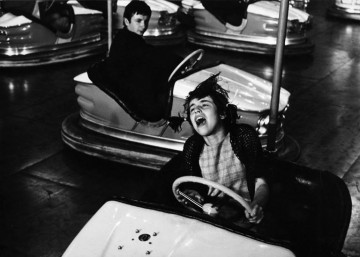

For that matter, the profound sense of mystery evoked by Bresson’s characters, including Mouchette, can’t be equated with the curiosity provoked by Igor and Rosetta, especially because Bresson’s characters always register as fixed essences and never as works in progress. When Rosetta rejects Riquet’s offer of a beer, then suddenly asks him for one and drains it in a single gulp, we’re led to believe that her previous avoidance of both liquor and sex might be motivated by a fear of becoming like her mother — and by a desire to succumb to both temptations that frightens her even more. In this wonderfully observant and beautifully performed comic sequence, Riquet’s clumsy attempts to show off first his skill at gymnastics and then his skill at drumming, followed by his efforts to get Rosetta to dance, are met by her with amusement, then bravado, and finally clunky gestures. This scene gives us a sense of the wonderful things the Dardennes can do with actors, which are a far cry from Bresson’s own formidable yet very different accomplishments with nonactors.

Rosetta is alive with a sense of urgency as well as currency, even though there’s nothing remotely preachy about it. American reviewers who insist on treating it as minor and then treat something like Dogma as a heady challenge seem to be implying that we’re all such infantile escapists at heart that we can’t possibly be interested in a movie that concerns anything as real as finding a job.

I’ve heard that one critic has attacked Rosetta for not being Brechtian. I’m tempted to counter that the veritable theme song of Brecht’s Threepenny Opera — “First comes bread, then comes morals” — could easily serve as one of Rosetta’s rationales for her behavior. But then I recall Hannah Arendt’s gloss on how this line was received in pre-Hitler Germany: It was “greeted with frantic applause by exactly everybody, though for different reasons. The mob applauded because it took the statement literally; the bourgeoisie applauded because it had been fooled by its own hypocrisy for so long that it had grown tired of the tension and found deep wisdom in the expression of the banality by which it lived; the elite applauded because the unveiling of hypocrisy was such superior and wonderful fun. The effect of the work was exactly the opposite of what Brecht had sought by it.”

I don’t think it’s possible to misread Rosetta in any of the ways outlined by Arendt, so perhaps I’m misreading the film critic. Clearly Rosetta isn’t esoteric or cerebral or difficult to understand; it isn’t remotely boring or even slightly pretentious. Its only crimes are that it isn’t in English (though it doesn’t have much dialogue anyway), it has something powerful to say about what’s happening right now across the planet, and millions haven’t been spent promoting it.