This appeared in the August 27, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

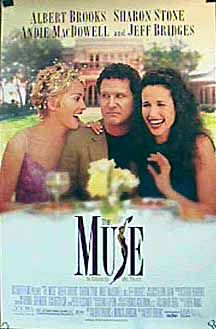

The Muse

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Albert Brooks

Written by Brooks and Monica Johnson

With Brooks, Sharon Stone, Andie MacDowell, Jeff Bridges, Mark Feuerstein, Stacey Travis, and Steven Wright.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

The Muse made me laugh, but not as much as the five Albert Brooks movies preceding it. It also made me think less, and that’s more of a problem. I don’t care whether Mel Brooks makes me think, but Albert’s a different matter. He’s a conceptual filmmaker unlike any other — a Stanley Kubrick among comedians whose premises need to be pondered, not simply accepted or rejected.

The Muse is a somewhat flimsy high-concept movie whose ultimate justification is that its subject is the manufacture of flimsy high-concept movies. It isn’t so much about a muse as about the apparent need for one. Steven Phillips (Brooks) is a well-to-do Hollywood screenwriter with a wife (Andie MacDowell) and two daughters — the first Brooks hero to have children — who’s desperate because everyone tells him he’s “lost his edge.” What does that mean? The movie doesn’t say, and Brooks, as usual, doesn’t spell it out. Presumably it doesn’t matter because behavior is all that ever interests him anyway: losing your edge is what happens when people say you’re losing your edge.

Eventually Steven regains his edge by enlisting the services of a professional muse named Sarah Little (Sharon Stone). His friend Jack (Jeff Bridges), an even more successful screenwriter who has been inspired by her, recommends her, but to clinch the deal Steven has to messenger over some of his scripts, ply her with gifts, book her into the Four Seasons, and buy her groceries. In return, she suggests he accompany her to an aquarium in Long Beach, where he’s inspired to write the screenplay that will redeem him: an idiotic “summer comedy” involving an aquarium and Jim Carrey.

A stupid idea? It’s supposed to be. The Muse is about the stupidity of people making movies in Hollywood — nothing new there. It’s also about the stupidity that drives them, organizes their behavior, and rationalizes their decisions — which is slightly new but not by much. Brooks, as usual, plays a whiner, so a good many laughs are about his whining in response to Sarah’s demands, especially after he becomes jealous of the attention she’s paying his wife, who’s starting to benefit from her services as much as he is.

Steven isn’t particularly distinguishable from Brooks’s earlier heroes, and the fact that he has daughters doesn’t wind up changing him much. Neither does the muse. In an interview in the August Playboy, Brooks suggests that the original concept for the movie came to him a long time ago: “The idea of something that inspires and helps creativity has always intrigued me. What is a muse? A muse is anything. Fifteen years ago, I had an idea about someone who follows a muse entity around the world in order to keep creating. That was an earlier version of this.” In this version the muse seems to serve mainly to reveal Hollywood’s idiocy and gullibility — much as the parody of cult religions in Bowfinger does — rather than to spark an examination of the creative process, serious or otherwise.

If Brooks thought Sarah were doing something special — and not simply starting Steven on his aquarium script and persuading his wife to go into business baking cookies only because they’re too neurotic to take these steps on their own — he wouldn’t go to such lengths to make sure that a Martin Scorsese movie needing her guidance was at least as silly and preposterous as the aquarium script. (Showing what good sports Scorsese, Cybill Shepherd, Rob Reiner, James Cameron, Spago chef Wolfgang Puck, and a slew of other guest stars are seems mainly a tacky way for Brooks to boast that he managed to secure their good-natured cooperation; none of the gags involving them is funny enough to justify them on strictly comic grounds.) And he wouldn’t eventually expose Sarah as a lunatic, then as a lunatic “running the asylum,” if he took her function as a muse even half seriously.

Yet if Brooks is interested in sketching out only the dumbest possible examples of high-concept movie ideas, he doesn’t follow through on his own dumb high-concept idea. The Muse‘s true subject isn’t inspiration but creative paralysis, though it never quite comes out and says so. A certain amount of mea culpa underlies the satire in all of Brooks’s features — one thing that gives them the edge Steven is said to have lost — but the self-criticism here has something desultory and defeatist about it. If the happy endings of Defending Your Life and Mother, his last two pictures, seemed hyperbolic to a fault, this one is bitter without having declared itself.

The execution of the script is perfect, as always, but it’s the laziest script Brooks has ever directed. The funniest sustained sequence in the movie has nothing to do with either the story or its theme: a party conversation between Steven and an Italian who barely speaks English that’s an almost musical development of cascading misunderstandings. It isn’t as good as Abbott and Costello’s “Who’s on first?” routine, but it builds to a nearly comparable delirium. It’s a sign that Brooks is running away from the conceptual purity of his earlier features and toward the kind of stand-up shtick he emerged from (his father was a radio comic).

The last time Brooks took on the movie industry — in his second feature, Modern Romance (1981), a work that won him the admiration and friendship of Kubrick — it was the nuts-and-bolts side of the business that interested him. As demented as the Brooks hero was in trying to end a long-term relationship, he was a consummate professional as a film editor working on a stupid SF movie. And part of what was so fascinating about Brooks’s writing was the subtle thematic counterpoint between the personal and the professional, as it showed that a man who couldn’t manage to edit his own life had no trouble editing someone else’s brain- dead movie.

By contrast, The Muse doesn’t quite find the nerve to tell us whether Steven is talented or untalented as a screenwriter, inspired or uninspired before or after Sarah comes along. Apparently it envisions an industry where talent is irrelevant and dumb ideas are the only currency. (A “humanitarian,” according to Steven’s memorable wisecrack to one of his daughters, is someone who hasn’t won an Oscar.) This might come close to being technically accurate, but it deprives us of an interesting hero. The brains and talent of other characters aren’t defined either; all we know about Jack, for instance, is that he has a very bankable professional profile and that he can’t hit a tennis ball across a net. It’s hard to accept Brooks’s definition of dumbness when he doesn’t bother to show us any clear signs of intelligence — something he’s always done one way or another in his previous features.

I suspect part of the problem is class. Starting with Lost in America, his third feature, Brooks’s heroes have been fairly upscale. But the world they inhabited never seemed as exclusively upscale as it does here — some of the funniest parts of Lost in America came when the lead couple had to make their way in the working-class world, which Brooks was able to show without any noticeable strain or exaggeration.

The ugly anonymity of certain generic American landscapes — coffee shops, roadside diners, malls, supermarkets — are usually part of his signature. The role played by locations in The Muse — mainly studio offices, mansions, and fancy restaurants, but most strikingly guest houses in the back of the mansions — seems less clearly defined and more haphazard; the excess of Los Angeles and environs appears to be taken for granted, so most of the minimalist poetry has been drained away.

A realist aesthetic has always been basic to Brooks, but we tend to forget that what we call realism — in the work of everyone from Emile Zola to David Denby — almost invariably derives from a class position. One very useful aspect of Denby’s film criticism, apart from its beautifully chiseled prose style, is the way it reliably, often hilariously, reflects a middle-class or upper-class blindness to the world everyone else inhabits. In his review of Eyes Wide Shut, for example, we’re told that “a prostitute who picks up [the hero] and takes him home is patently too beautiful and well educated to be working the pavements,” though the only on-screen evidence of her education I could spot was a sociology textbook and an Oscar Peterson CD. Clearly middle-class constructions of street hookers rule out such cultural markers — though apparently not those of ideologically correct specimens such as Woody Allen’s undereducated prostitutes and convicts, who are apt to use terms like “dem” and “dose.”

Part of the strength of Brooks’s realism has always been that he never even approximates Allen’s or Denby’s class-bound blunders. Yet though he clearly understands the myopia of the wealthy people in The Muse, he refuses to look very far beyond their limitations — and almost seems ready to accept their world as a near facsimile of his own. For the most part, the people in this movie are too narrow to solicit as much interest as their counterparts in Brooks’s earlier pictures. The only exceptions are Stone and Bridges, both of whom get a few wonderful opportunities to exercise their inadequately recognized comic gifts. Bridges at least had the last Coen brothers movie, The Big Lebowski, to stretch out in, but I don’t remember Stone having a chance to be this funny since Basic Instinct. She’s as good a reason as any to go see The Muse, but don’t go expecting much more.