From the Chicago Reader (August 6, 1999). — J.R.

The Thomas Crown Affair

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by John McTiernan

Written by Alan R. Trustman, Leslie Dixon, and Kurt Wimmer

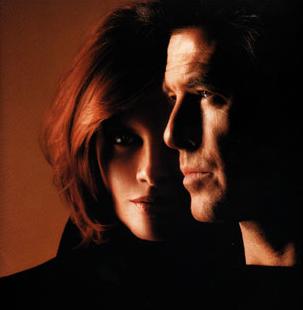

With Pierce Brosnan, Rene Russo, Denis Leary, Frankie R. Faison, and Faye Dunaway.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Seeing an original movie and its remake in reverse order is a bit like reading a novel (as opposed to a novelization) after you’ve seen the movie. It usually distorts your sense of priorities, forcing you to see the ideas and images of the original in terms of the remake. That’s why I suspect I’ll never know whether the remake of The Thomas Crown Affair is inferior to the 1968 original. Both are entertaining pieces of trash, but look at them in succession — in either order — and they start to undermine each other.

Both are about a classy investigator for an insurance company (Faye Dunaway in 1968, Rene Russo in 1999) going after a debonair zillionaire (Steve McQueen then, Pierce Brosnan now) who pulls off elaborately planned, outrageous robberies with hired helpers just for the fun of it. In the original, set in Boston, he robs a bank; in the remake he steals a Monet from New York’s Metropolitan Museum and then, just to show how cool he is, replaces it without getting caught. What starts off as a sassy battle of wills between the two characters quickly turns into an upscale romance, and the lure of amorality for the leads is probably just as important as the omnipresent trappings of wealth.

“Part of the fun of movies,” Pauline Kael wrote in one of her key position papers (“Trash, Art, and the Movies,” 1969), “is that they allow us to see how silly many of our fantasies are and how widely they’re shared. A light romantic entertainment like The Thomas Crown Affair, trash undisguised, is the kind of chic crappy movie which (one would have thought) nobody could be fooled into thinking was art. Seeing it is like lying in the sun flicking through fashion magazines and, as we used to say, feeling rich and beautiful beyond your wildest dreams.”

In the same essay Kael expressed her dismay at reading a letter in a Boston paper from a Cambridge student who took The Thomas Crown Affair as a serious allegory. But that was before the teen and preteen markets took over most of the film business and college professors started speaking seriously about Star Wars in relation to the Aeneid. Even though George Lucas is now treated with more respect than Virgil, I doubt that anyone’s going to assign cultural credentials to adult tripe like the Thomas Crown remake. It’s a piece of disposable fluff — though that’s exactly what’s so appealing about it. Is seeing it “like lying in the sun flicking through fashion magazines”? Pretty much, though maybe it’s more like flicking through Playboy features about lifestyles of the wealthy. And I’m not sure younger viewers will want to buy into those fantasies.

In at least a couple of areas I think the story has been improved. The means by which Brosnan’s Crown, a Scottish self-made man in New York, steals and replaces the Monet are much more elaborate and fun to second-guess than the scheme by which McQueen’s Crown, a Boston Brahmin, robs a bank, and the script is clever enough to introduce some further plot twists about him. Russo’s insurance company investigator is much smarter, hipper, and more self-assured than Dunaway’s — until the movie deems it necessary to cut her down to size. Not that Dunaway played a slouch in the original, but that was before feminism had made much of a dent in the culture. Her youth also undoubtedly worked against her character’s authority; she was in her mid-20s at the time, 11 years younger than McQueen. (Dunaway wasn’t allowed to push her other Superwoman characters very far either; she remained a sexist stereotype in the 1976 Network and a horror-movie version of Joan Crawford in the 1981 Mommie Dearest.) As if to prove how far we’ve come, an older, wiser, tougher Dunaway is cast as Crown’s psychiatrist in the remake — a part that would have been inconceivable in the original, though she’s still sufficiently deferential to call him Mr. Crown. And though the issue of Rene Russo’s age never occurred to me while I was watching the remake, even when she took her clothes off, I was surprised to read that she’s 45. Until Crown’s greater genius knocks her down a peg, her character is basically a Renaissance goddess — rivaled only by Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct — and her performance is the best thing in the movie.

As for Crown, the issue isn’t so much Brosnan versus McQueen — one inexpressive hunk versus another — as it is hip inexpressiveness in the 60s versus hip inexpressiveness in the 90s. When the original Crown pulls off his first bank robbery, he lights a sleek cigar and laughs loudly and contentedly to himself — behavior that would never even occur to the second Crown, basking in his own triumph after filching the Monet. I suspect a good part of the difference has to do with Brosnan’s post-Eastwood and Schwarzenegger affectlessness, no doubt given additional spin by his stint as James Bond.

Much as this remake pays some respect to Dunaway by casting her in a small part, it acknowledges Michel Legrand’s effective score for the original by integrating its theme song, “The Windmills of Your Mind,” into the latter portions of Bill Conti’s score. It’s a nice gesture, though it doesn’t make up for the otherwise inferior music on the sound track.

One thing that’s missing from the remake was a source of much comment in the original — the split screen, a technique introduced at Expo ’67 and, as Dave Kehr remarked in his Reader review, “hailed as the future of movies,” though a few years later it was “deader than the monorail.” (It was also used to great utopian effect in Woodstock in 1970.) In the 1968 Thomas Crown Affair Pablo Ferro used it mainly to alternate between showing several images at once — most often separate details of a single event — and showing a single image broken up into several interlocking squares. Even on a scanned video, the only way I’ve seen the original, his use of the technique is pleasurable, though it’s strictly stylish embroidery rather than an organic breakthrough. Much of what makes it striking is the beauty of Haskell Wexler’s cinematography, which whenever the story meanders holds one’s interest with patterns of light flashing on a rain-streaked car window or with the rhythms of certain shots going in and out of focus.

But a movie of this kind may need a big screen to carry any weight as myth — and without that mythic weight it dissolves into thin air. So part of my preference for the second Thomas Crown and the Fantasyland he moves through is how big they were at 900 N. Michigan. Forced to watch the original on a small screen, I can’t properly judge its strength, even as a piece of fantasy fluff — though millions of people who watch movies on video seem to think they can.