There are few films of the past decade that have irritated me quite as much as Van Sant’s idiotic remake of Psycho, and in some ways I was irritated even more by the rationalizations some cinephiles came up with in their tortured efforts to justify it. I tried my best to behave like a gentleman towards Lisa Alspector, the Reader film reviewer whose capsule sparked my longer review in the December 25, 1998 issue, but I don’t know whether or not I succeeded. — J.R.

Psycho

Rating — Worthless

Directed by Gus Van Sant

Written by Joseph Stefano

With Vince Vaughn, Anne Heche, Julianne Moore, Viggo Mortensen, William H. Macy, Robert Forster, Philip Baker Hall, Ann Haney, and Chad Everett.

Psycho has never been one of my favorite Alfred Hitchcock pictures. The first time I saw it, during its initial release in 1960, I’d already read the Robert Bloch novel it’s based on, a fairly routine horror thriller, so the surprise ending was anything but surprising. I saw the movie back-to-back with Let’s Make Love, which I liked a lot more. Yves Montand spoke English awkwardly, but Marilyn Monroe was irresistible — for practically the only time in her late career, she played a character who was smart and feisty. In Psycho Janet Leigh, whom I also had a crush on, was pretty feisty as well. But after she got knifed to death in the shower early on, there was only drab Vera Miles to contend with, not to mention additional gore, cumbersome exposition, John Gavin, and reams of psychobabble about Norman Bates that I could never fully swallow (or even entirely follow).

Psycho placed second among the box-office winners of 1960, after Ben-Hur; Let’s Make Love didn’t even make it into the top 20. The critical fates of the two pictures have been similarly disparate: for many people, Psycho remains Hitchcock’s greatest picture and one of the greatest Hollywood movies ever made, but even most aficionados of director George Cukor wouldn’t call Let’s Make Love one of his dozen best pictures. Now that many critics, including me, regard Hitchcock as one of the key artists of cinema — which wasn’t the case in 1960, even for most French critics — I can readily concede the error of my judgment at the time. But that doesn’t mean Psycho has ever captured my heart the way Let’s Make Love once did.

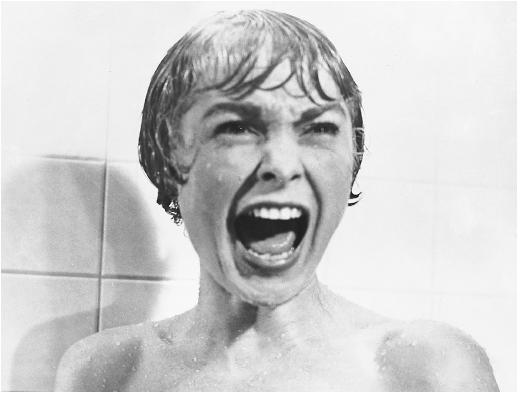

Today I find Psycho a film of corrosive brilliance — with some ugly and indifferent patches (almost everything involving Vera Miles, John Gavin, and, above all, the psychiatrist played by Simon Oakland) — that works on my mind and nerves more than on my feelings. This may be in part because the shower stabbing has become the most drooled-over sequence in the history of cinema. Whatever my ideological and visceral misgivings about the Odessa Steps sequence in Eisenstein’s Potemkin — which was fetishized almost as much as the Psycho scene — I can’t accuse it of expressing the kind of puritanical misogyny Hitchcock’s piece of bravura does or of spawning a cottage industry in gleeful on-screen woman carving. But let me be just. The first 53 minutes of Psycho — very nearly the first half, everything from when we enter a seedy Phoenix hotel room to when we see the sinking of a car in a marsh, capped by Norman Bates’s triumphant grin — constitute one of the supreme achievements of Hitchcock’s career. What makes it so remarkable is not simply the hysteria provoked by the repressed sexuality but the no less troubled feelings it arouses about money — too little money, too much money, money as a signifier of despair and twisted human impulses. Indeed, it’s the interplay between sex and money (as ferocious here as it is in Charlie Chaplin’s equally misogynistic and misanthropic Monsieur Verdoux) that accounts for the extraordinary sense of dread that infuses these 53 minutes — an interplay of perpetual displacement and substitution that culminates in the simultaneous descent into slime of both the sex object and the $40,000 she stole. The crime of murder both effaces and permanently conceals the crime of theft around the same time that our moral position shifts from being complicit in an act of spontaneous theft to being complicit in an act of spontaneous murder.

Critics have always paid more attention to the sex in Hitchcock’s Psycho than to the money — though money informs our perception of the sex at every turn. But the money gets star billing in Gus Van Sant’s stupid remake: not the $400,000 (40 years of inflation) stolen by Marion Crane (Anne Heche), but the money that controls our discourse about the film — the rationalization of moneygrubbing as an aesthetic strategy that freely passes from the promotional material to the critics. That the rationalizers in this case include a talented filmmaker, his publicists, and some of his defenders only adds to the overall confusion.

Let’s begin with the talented filmmaker, the director of three remarkable features (his first three: Mala Noche, Drugstore Cowboy, and My Own Private Idaho), many first-rate but lesser-known short works, and three problematic but at least semi-defensible commercial features (Even Cowgirls Get the Blues, To Die For, and Good Will Hunting). Here’s the reason Gus Van Sant gave for remaking Psycho: “I felt that, sure, there were film students, cinephiles, and people in the business who were familiar with Psycho, but that there was also a whole generation of moviegoers who probably hadn’t seen it. I thought this was a way of popularizing a classic, a way I’d never seen done before. It was like staging a contemporary production of a classic play while remaining true to the original.” (To ensure that Hitchcock’s classic gets popularized Universal stopped distributing it on video and laser disc a month ago.)

In her capsule for the Reader‘s movie listings, Lisa Alspector rationalizes the argument this way: “Plays are created in hopes that they’ll be staged by many directors; only convention has persuaded us to think of movies differently — remakes are often evaluated as if originality were somehow quantifiable, absolute, or the necessary objective of art. With this thriller — which is innovative in the extreme to which it takes the practice of copying — director Gus Van Sant reminds us that all forms can be used as blueprints and that hommage may be a euphemism.”

I can’t disagree with a word Alspector says. It’s irrefutable that “only convention” has persuaded us to think that movies — or, for that matter, poems, short stories, novels, paintings, sculptures, and buildings attributed to single artists — can’t be remade just as plays are restaged. But it’s also true that Brian De Palma has been remaking Hitchcock’s films for the past quarter century — copying themes, plots, camera movements and angles, even hiring Hitchcock’s most distinguished composer, Bernard Herrmann, to copy some of his own Hitchcock scores for two of these pictures, Sisters and Obsession. He’s even been applauded for doing this by Pauline Kael and many of her disciples, some of whom find the trashy results superior to the Hitchcock originals — mainly, it appears, because they’re so trashy. By this standard, Van Sant’s “extreme” innovation in his Psycho remake is to limit his imitations to a single Hitchcock picture and add fewer interpolations of his own. But the implication of Alspector’s remark is that if Hitchcock — or Robert Frost, William Faulkner, Jackson Pollock, Henry Moore, or Frank Lloyd Wright — were freer from established conventions, he might have created his works in hopes that they’d be redone by other people. Maybe I’m misconstruing the leap she makes from the vantage point of creators (“plays are created”) to the vantage point of consumers (“us”) by assuming that she believes these vantage points are or should be identical. But where money is concerned, our society made that leap a long time ago; the final words of the closing credits of “Gus Van Sant’s” Psycho inform us that Universal Pictures — not Alfred Hitchcock or Gus Van Sant, novelist Robert Bloch or screenwriter Joseph Stefano — is the legal author of the film we’ve just been watching. That statement couldn’t appear on any film in France, where the authorship of the director is established by French law. I could argue further that it’s “only convention” that has persuaded us — Alspector included — that this Psycho somehow “belongs” to Gus Van Sant and not to Universal Pictures.

In any case, I certainly couldn’t argue with Alspector’s assertion that originality isn’t quantifiable, absolute, or the necessary objective of art. I also agree that “all forms can be used as blueprints and that hommage may be a euphemism.” I would add that what hommage is usually a euphemism for is plagiarism, and that it’s important to ask what the blueprints in question are for. Theoretically, a nearly shot-by-shot, line-by-line remake of any movie could produce something marvelous, fresh, and revelatory, at least if an artist had a viable artistic program to go with it. Practically, I would argue, Gus Van Sant’s Psycho is a piece of dead meat. Alspector finds that “the gentle incongruities among the costumes, dialogue, and social mores” of the Psycho remake, in spite of the 1998 setting, “make the movie resemble a dream” — her most provocative and interesting defense of the movie. But the fact that I find the first 53 minutes of Hitchcock’s Psycho even more like a dream — a vastly more interesting, compelling, and affecting dream — surely gives the lie to Van Sant’s claim that all he’s doing is “popularizing a classic,” especially if nightmare is being replaced with camp.

So if we discard Van Sant’s claim and stick to Alspector’s, what do we have to work with apart from gentle incongruities? (Some of these, incidentally, like Julianne Moore’s lewd wink at Vince Vaughn when she and Viggo Mortensen check into the Bates Motel — no equivalent to which can be found in the original — are not so gentle. And in the same scene, another throwaway addition that clearly is a gentle incongruity — the price of the room they’re renting, $36.50 — registers as sloppy absent-mindedness given the adjustments made elsewhere for inflation.) If Alspector is saying that, approached in the proper spirit — expecting nothing but charming bilge, which is the most one can hope for in most new movies anyway — the new Psycho is worth seeing, she’s right, at least if you find it charming. I didn’t. The biggest theoretical problem for me with the whole enterprise is the assumption that color could be an adequate “equivalent” to black-and-white — an assumption clearly made by money, not aesthetics. Manny Farber once perceptively remarked that “the first third of Psycho is as bare, stringent, minimal as a Jack Benny half hour on old TV” — and by “old TV” he means, more than anything, black-and-white. There’s nothing remotely bare, stringent, or minimal about the first third of the new Psycho, because the color provides far too much extraneous and therefore useless information, so the nightmarish pacing, tone, and texture of the original isn’t even hinted at; if it’s a dream, it’s much closer to Pee-wee’s Playhouse than Jack Benny. For all his ambivalence about Psycho, Farber was particularly impressed by the drab desperation realistically described by the scenes with Leigh in Phoenix. This depressive realism has usually been labeled a complete departure for Hitchcock, but it has one revealing precedent — the most underrated American Hitchcock film, made only three years earlier and also in black-and-white (and with Vera Miles), The Wrong Man.

Critic James Naremore recently told me he thought this was the most depressing commercial film in American cinema, and surely there’s no other work of Hitchcock’s that more vividly details the state of being economically downtrodden and hopelessly ensnared in an uncaring system. Psycho begins in more or less the same state of everyday depression and banality before getting lost in gothic potboiler details; Marion Crane’s hallucinatory cross-country flight by car punctuated by imagined conversations is every bit as harrowing as Henry Fonda’s entrapment in a cell, and the real estate office she’s in flight from is every bit as uncomfortable as the public spaces in the earlier film. This if anything is what makes Hitchcock’s Psycho a classic text. Yet nothing could be further from what the remake has in mind — assuming it has anything in mind — thanks to the candy-box colors. Chris Doyle, the cinematographer, happens to be one of the key figures of the Hong Kong new wave, at least as important to Wong Kar-wai as Raoul Coutard was to Jean-Luc Godard; but using him here is about as irrelevant and pranky as smearing Renoir pinks over a van Gogh landscape. However, “only convention” has persuaded us that Renoir pinks don’t have a legitimate place on a van Gogh canvas, and the minute someone with money decides, rightly or wrongly, that more money can be made by applying them, you can bet that some reviewer somewhere will be waiting to offer aesthetic justifications for the maneuver.

Universal might have miscalculated this time. With a great deal of fanfare, it announced that Van Sant spent the same number of days shooting his film as Hitchcock did, and because Hitchcock opened the film without press screenings, the new version followed suit. But Hitchcock’s biggest piece of ballyhoo was insisting that no one be admitted to see the picture after it started; if Universal is making any such demands, it clearly isn’t honoring them — only ten were in the audience at the 6:50 weekday show at 600 N. Michigan when it started, but more than a dozen were watching half an hour later. The implication, despite Universal’s careful reasoning, is that 60s audiences were hip enough to appreciate what Psycho was and that 90s audiences are hip enough to appreciate what the new Psycho isn’t. But it’s positively quaint to imagine that Universal would refuse anyone’s cash in 1998 as it could — and did — in 1960.

What is the 1998 conjured up by Gus Van Sant for his ersatz Psycho? Apart from being a 1998 whose characters have never heard of Hitchcock’s Psycho — a SF landscape if there ever was one — it’s one where all the rib-nudging “director’s touches” go against the moral and affective grain of the original without offering much besides doodling in its place. The last line in the film alludes to a fly, so we get a cumbersome close-up of a fly buzzing over a hotel sandwich shoved into the opening scene and lots of periodic buzzing on the sound track. Hitchcock once told François Truffaut that the original should have shown Leigh’s breasts in the opening scene; instead of obliging, Van Sant offers a glimpse of Mortensen’s ass, then gets around to showing us Heche’s ass after her character has become a hacked-up corpse.

Despite such thoughtfulness, Van Sant’s Psycho has to be the least sexy movie I’ve seen all year. In contrast to the remarkable vibrancy and focus of Leigh, Heche gives such a juiceless and inane performance that it becomes impossible to care much about either her theft or her murder; Vince Vaughn as Norman Bates is scarcely any better, even if we get to hear him jerking off while he watches Heche undress, a courtesy denied Anthony Perkins when he was peeping at Leigh. (Innocent query: what does this add to our understanding of Bates?) By contrast, William H. Macy represents a marginal improvement over Martin Balsam as the detective Arbogast, and Robert Forster as the psychiatrist is a vast improvement over Simon Oakland. So what?

In contrast to the pithy final shot of the original, we get a sprawling crane shot that meanders for an eternity so the endless parade of extra credits can roll past. Is that paying homage to a 1960 classic or to a 1998 studio? A few added lines of dialogue, surrealist montage inserts in the two murder scenes, a substitution of a country-and-western tune for the Eroica Symphony on Bates’s record player, and other pointless replacements or supplements reveal not so much a desire to interpret or reinvent the film as an idle flight from boredom or bemusement — the logical outcome of Van Sant’s doomed and misguided experiment. That doesn’t mean that flacks like my colleagues and I won’t be toting up all the meaningless variations for weeks to come. After all, part of our job is to supply meaning and significance where there is none.