From the Chicago Reader (June 27, 1997). — J.R.

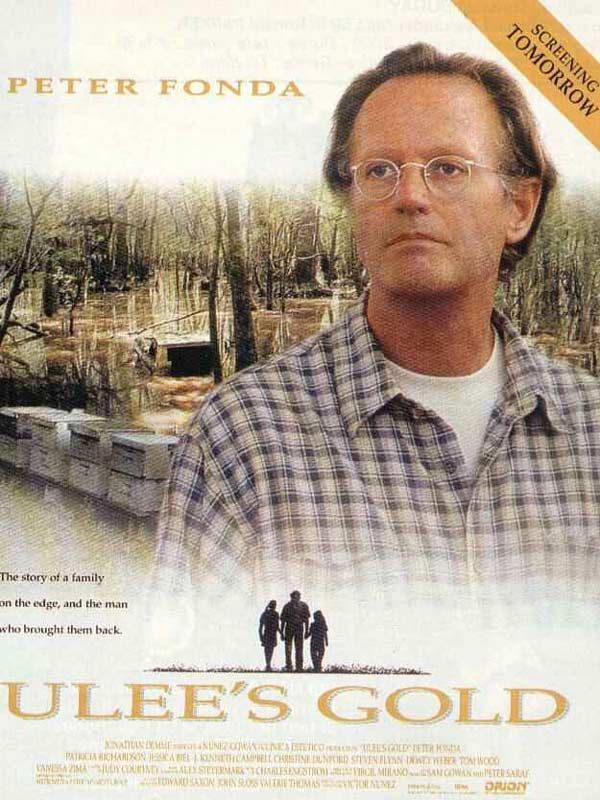

Ulee’s Gold

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Victor Nunez

With Peter Fonda, Patricia Richardson, Vanessa Zima, Jessica Biel, Christine Dunford, J. Kenneth Campbell, Steven Flynn, Dewey Weber, and Tom Wood.

The character-driven stories in all four of writer-director Victor Nunez’s features to date — Gal Young ‘Un, A Flash of Green, his masterpiece Ruby in Paradise, and now Ulee’s Gold — are defined by their regionalism: Nunez operates exclusively as a Florida independent. Whether he’s adapting a Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings short story set in the 20s or a John D. MacDonald novel (his first two films) or writing an original script (the second two), Nunez bases his art on a sense of place so solid that the texture of the settings is part of his subject.

The fact that all his films are relatively slow moving also has something to do with the Florida settings. Former residents of that state have told me that his movies capture not only a sense of the place but its rhythms, and judging from the novels with Florida settings I’ve read in recent years — John Updike’s Rabbit at Rest and the three wonderful Hoke Moseley novels of Charles Willeford (Miami Blues, Sideswipe, and New Hope for the Dead) — this isn’t just Nunez’s take on the region.

But in most people’s minds a “slow” movie usually translates into an art film. And there is something about the way Nunez, who works as his own camera operator, lingers over shots and settings that makes his features novelistic in the good sense. When Ulee Jackson (Peter Fonda), the beekeeper hero of Ulee’s Gold, drives down to Orlando to see a couple of hoods, Eddie (Steven Flynn) and Ferris (Dewey Weber), he meets them in a dive called the Orange Blossom, and his slow progress across the room, with the camera closely flanking him in the foreground, is like a paragraph of atmospheric description. Similarly, the interludes in this movie about how to make, process, and store tupelo honey never seem tedious or pointlessly extended; they contribute to the texture of the story Nunez is telling.

If you’re as rattled as I am by the mindless rapidity of such empty junk heaps as Speed 2: Cruise Control and Batman & Robin, leisurely pacing of this kind is likely to register as a form of respect for the viewer’s intelligence and observation. And such a strategy can only pay off when it comes to filming a relatively inexpressive actor like Fonda: he and Nunez both know how to make Ulee an iconographic object of mystery, striking chords in the mythologies suggested by this lone hero. Clint Eastwood, John Wayne, and Fonda’s father, Henry, are all stars who’ve filled this kind of role in the past, inviting viewers to project their own notions of isolation onto the actors’ hardened features. The critics who’ve been declaring that Peter Fonda’s Ulee is the performance of his career are really saying that Nunez and Fonda are smart enough to allow this alchemy to work. Fonda has noted that his father used to keep bees, and we’re clearly being invited to make other connections with Henry Fonda, an association that gives Peter Fonda’s performance its weight; in many cases his acting is not so much a matter of accumulating expressions and gestures as it is keeping them minimal, allowing his lineage to shine through.

This approach helps to explain why Ulee’s Gold works pretty well as a movie; it works as a novelistic movie for similar reasons. The story is basically a tale of redemption — but if you compare American novels about redemption with American movies about redemption, they’re not much the same. Novels such as Saul Bellow’s Herzog and some of Updike’s Rabbit books tend to be meditative studies of inner growth and healing — internal processes that readers are invited to chart over extended periods of time. American movies tend to make inner growth either an unfathomable postulate, as in Raging Bull, or an overt change of heart, like Samuel L. Jackson’s sudden abandonment of his hit-man career in Pulp Fiction — that is, it’s either invisible or it’s in your face. In this respect Ulee’s Gold is a lot closer to Bellow or Updike than it is to Scorsese or Tarantino.

Unfortunately, the story Nunez chooses to tell here is fairly familiar movie material, though it’s decked out with some unnecessary and cumbersome literary trappings. Ulee, a withdrawn man who works and lives in the tupelo marshes of the Florida panhandle, is a Vietnam vet, the only one among his buddies to survive the war. Embittered by the death of his wife Penelope six years earlier (“I practically fell off the planet”), Ulee is also haunted by the collapse of his family, apparently the result of her loss. His son Jimmy (Tom Wood) retreated into a life of crime and was arrested for robbery and imprisoned; subsequently his wife Helen (Christine Dunford) became a drug addict and abandoned their two daughters, Casey (Jessica Biel) and Penny (Vanessa Zima). When the movie opens Ulee is raising his granddaughters — Casey is a teenager, while Penny’s still in grammar school — but has pretty much washed his hands of his son and daughter-in-law. Then events compel him to become involved in their lives again. (If you don’t want to learn any more of the plot, stop here.)

Jimmy calls Ulee from prison to report that Helen is staying with his two former partners in crime, Eddie and Ferris, in Orlando and that they want Ulee to take her off their hands. Ulee grudgingly complies, but when he sees Eddie and Ferris he discovers they have another reason for summoning him: having extracted a confession from Helen in her drug-addled state that Jimmy hid an additional $100,000 before his arrest, they want Ulee to recover the loot and fork it over, and they threaten his daughter-in-law and granddaughters if he fails to cooperate.

Ulee’s given name is Ulysses, his wife was Penelope, and he saves a woman named Helen, but the reference to Homer’s Odyssey is far-fetched given what we know about the characters. Perhaps Ulee’s past as a Vietnam vet is supposed to stand in for Ulysses’ war experiences, and his “rescue” of Helen somehow alludes to Helen of Troy, but the parallels with Homer are really forced when it comes to Ulysses’ homecoming. Is the reconstitution of Ulee’s family supposed to correspond to Ulysses’ return to his still living wife, when he rids their house of her suitors? Whatever correspondences Nunez had in mind, none carries any conviction.

Moreover, Nunez’s screenwriting imagination seems stunted by Hollywood genre films when it comes to the family members who need to be brought back into the fold, Helen and Jimmy, and to Jimmy’s former partners, Eddie and Ferris. Helen’s transformation from hysterical addict strapped to her bed to born-again mother baking cookies a few days later is merely assumed, not charted, and Jimmy’s conversion is comparably sketchy; Eddie and Ferris are simply standard-issue hoods.

But when it comes to all the other characters, Nunez’s film is novelistic in the best sense; he’s as good a director of actors as you’re likely to find in American movies right now. Patricia Richardson (who stars in the popular TV series Home Improvement) plays Ulee’s neighbor and tenant Connie Hope, a twice-divorced nurse who helps with Helen’s drug cure; even if she is saddled with a symbolic last name, it’s hard to think of a more lifelike character in any movie I’ve seen this year. Nine-year-old Vanessa Zima as Penny — another professional — has a wonderful way of handling reactions in emotionally charged scenes, and most of her costars aren’t far behind. The attentive way Nunez films his entire cast is as resourceful and evocative as the way he films his locations; even the less realized characters and the more familiar parts of the plot spring to life under his quiet and patient gaze.