This review of a major film, Andre Téchiné’s Les voleurs (Thieves), that was (perhaps typically, at least for this period) completely ignored in The New Yorker — along with Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man from the previous year — appeared in the December 27, 1996 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Thieves

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Andre Téchiné

Written by Téchiné, Gilles Taurand, Michel Alexandre, and Pascal Bonitzer

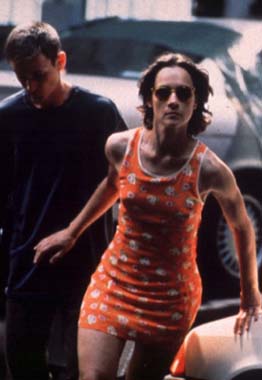

With Catherine Deneuve, Daniel Auteuil, Laurence Côte, Fabienne Babe, Julien Riviére, Benoît Magimel, Didier Bezace, and Ivan Desny.

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

“Before Christ was a time of orgies. Then came love.”

“Love’s less fun.”

“Probably. In orgies you give your all. No more, no less. In love, it’s never enough. It’s always too much or not enough.” –a conversation in Thieves between a philosophy professor (Catherine Deneuve) and a policeman (Daniel Auteuil) in love with the same woman

When was the last time you saw a movie that was truly for as well as about grown-ups? Whatever the virtues of Breaking the Waves, a mature point of view certainly isn’t one of them. The English Patient is at most a feature for dreamy young adults (especially those who consider it romantic for a character to become a Nazi in order to spend time with a former lover’s dead body), and even the good points of The Crucible and Ghosts of Mississippi don’t include the sort of insights that ought to come with age. Mars Attacks!, which grows in stature and audacity the more I think about it, is cannily likened by critic David Ehrenstein to the work of Alfred Jarry — making Nicholson’s fatuous president a version of Pere Ubu — but the merits of Jarry aren’t exactly those of adults. Even the adept romantic comedy One Fine Day, which has a lot to say about the perils and complications of being a single parent, intermittently takes leave of its grown-up concerns and traffics in the contrivances and coincidences of its elected Hollywood genre.

But André Téchiné’s remarkable Les voleurs — shorn of its definite article to become Thieves for stateside consumption — fulfills this category, though it does so in a way that may frighten off some viewers. A pessimistic film, but very far from a cynical one, Thieves postulates a fatalistic world bound by family origins and intense romantic longings in which every character is trapped into becoming a thief of one kind or another, emotionally as well as existentially. (The philosophy professor and the cop quoted above are only two of the guilty parties.) The fact that its writer-director is middle-aged surely has a great deal to do with the vision of life and life’s possibilities the film has to offer.

Born in 1943 in Valence d’Agen, Téchiné wrote criticism for Cahiers du Cinéma for four years in the mid-60s, including the period when Jacques Rivette was its editor. Téchiné went on to become an assistant to Rivette on L’amour fou before directing his first feature in 1969. His early features — Paulina s’en va (1969), French Provincial (1974), Barocco (1976), and The Bronte Sisters (1978) — are basically the work of an intelligent if not especially original cinephile. But he asserts that starting with Hôtel des Amériques (1981), the first of his films with Catherine Deneuve, there is a change — which I have to take on faith, because I haven’t seen any of his 80s films. (“From Hôtel des Amériques onward my films are no longer genre films,” he said a few years ago. “My inspiration is no longer drawn from the cinema.”) Certainly by the time he made My Favorite Season (1993) and Wild Reeds (1994) his focus was clearly and squarely on life, and his sense of film rhythm was derived most of all from what his actors were doing, even if the cinematic intelligence that shaped his early work had been not so much discarded as reconfigured.

The unusually well-defined cast of characters includes a family of thieves living in the mountains in southwest France — a widower and grandfather named Victor (Ivan Desny), his eldest son Ivan (Didier Bezace), Ivan’s wife Mireille (Fabienne Babe), and Ivan and Mireille’s son Justin (Julien Rivière) — as well as Ivan’s kid brother Alex (Auteuil), who has rebelled against his family by becoming a cop in a Lyons suburb. Then there’s Juliette (Laurence Côte), a former lover of Ivan who becomes a lover of both Alex and Marie (Deneuve), her former philosophy teacher. And there’s Jimmy (Benoît Magimel), Juliette’s brother, another thief, who works for Ivan. The action pivots on an attempted car heist at a railroad yard during which Ivan is killed — an incident that occurs just before the film starts.

Filmmaker Olivier Assayas, a former screenwriter for Téchiné, has compared Thieves to a William Faulkner novel, and it’s easy to see what he means. The narrative — consisting of a prologue, five sections, and an epilogue — is fluid and easy to follow, but it leaps around in time and switches between the viewpoints of Justin, Alex, Marie, and Juliette. The Faulkner novel it most closely resembles is The Sound and the Fury, which unfolds over four days, beginning with the viewpoint of the character who understands the least about the events taking place — an idiot named Benjy — before moving backward in time to the viewpoint of Benjy’s brother Quentin, then forward to the viewpoint of a third brother the day before Benjy’s narrative, and concluding with a third-person description of the day after Benjy’s account. Both The Sound and the Fury and Thieves also have a central female character who’s loved obsessively by two of the narrators: Faulkner’s novel has Caddie, who’s loved by her brothers Benjy and Quentin, and Téchiné’s film has Juliette, who’s loved by Alex and Marie.

The novel begins and ends with Benjy’s innocent reading of troubled family events, and Thieves begins and ends with Justin. After we hear a cacophony of offscreen voices behind the credits — the voices of the various characters drifting together and apart like lines in a fugue — we begin with Justin’s discovery of the death of his father Ivan, whose body has been brought home and placed in the living room, and wind up meeting all the major characters except Marie as Justin encounters them over the course of a day. After this prologue, we switch to Alex in Lyons a year before Ivan’s death, when he first meets Juliette, who’s brought to his office for shoplifting, and we follow his story — which also involves Ivan, Jimmy, and Marie — until we arrive again at the day after Ivan’s death and at the same family home, only now the viewpoint is Alex’s. (The repetition of the action extends to such details as a plane flying overhead, and the mountains and heavy snowfall, along with certain family details, call to mind Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player.)

Shortly after Alex and Juliette return to Lyons, she leaves him to see Marie, and Marie takes over the narrative. Then the story goes back six months to take up Juliette’s version of events prior to Ivan’s death — a section that concludes with the attempted car heist. Then we return to Justin a day after the events of the prologue, at his father’s funeral; pass back to Alex ten days after Ivan’s cremation; and finally return to Justin many months later.

Flashbacks as they’re ordinarily understood have no place or function here — because, as Téchiné himself has noted, they’re linked to linear and causal assumptions the film doesn’t share: “We wanted the story to develop without using the convention of the flashback, which is intended to show the causes. We preferred to interweave the causes and the consequences by moving backward and forward around the central event, Ivan’s death. That moment causes all the upheaval and turbulence to which the characters will be subjected.” Though much of the film is clustered around the attempted heist — leading to a narrative structure that suggests Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing and Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, which was patterned in part after Kubrick’s film — there are no thriller mechanics in Thieves. In fact, the abortive heist is probably the weakest scene in the film for precisely that reason; it was researched and plotted in detail — with cowriter Michel Alexandre, a former policeman who also scripted Bertrand Tavernier’s police procedural L.627 — but it’s sometimes an awkward intrusion because its mechanics seem to come from another movie. (It’s a familiar syllogism in French cinema that using elements from a certain genre results in a film of that genre; thriller elements or no, Thieves is not a thriller.)

If there are three more beautifully and complexly realized performances in a 1996 film than those of Deneuve, Auteuil, and Côte in Thieves, I haven’t seen them. Côte, giving what is probably her best performance to date, has been seen in Tacchella’s Traveling Avant, Godard’s Nouvelle vague, and Rivette’s The Gang of Four and Up Down Fragile; Juliette’s two suicide attempts, both convulsive and terrifying scenes, are only two examples of what Côte can do with this provocatively unfixed and oscillating character — who’s even more provocative when she mysteriously yet convincingly becomes both settled in her identity and all but irrelevant to the action near the film’s end, after having defined most of its troubled center. (The unconventional narrative structure repeatedly displaces the characters, profoundly shifting our perception of them.)

Téchiné has worked before with Deneuve in Hôtel des Amériques, Scene of the Crime, and My Favorite Season, and with Auteuil in My Favorite Season — in which the two actors played a sister and brother haunted by unrealized incestuous longings. Thieves has another sister and brother who seem similarly haunted, Juliette and Jimmy, but here Deneuve and Auteuil play strikingly different characters, a professor and a cop, uneasily bound together by their rivalry for the same woman. In a curious way Thieves turns into a kind of love story between these hopeless loners — an ex-wife, mother, and grandmother who’s fallen for another woman for the first and only time; and a divorced cop from a family of thieves who has also “crossed to the other side” of his destiny only to find himself in more or less the same place. When Marie records Juliette’s life story or when Alex snaps a picture of Marie after she’s fainted in his apartment, each of them is functioning as a thief and a hoarder, yet it’s in the few moments of generosity and camaraderie between these two lost individuals that the film finds some measure of hope.

Deneuve, who’s developed since her first major roles in the 60s (including The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Repulsion, Belle de jour, Mississippi Mermaid, and Tristana) from a glamorous star to a remarkably subtle actress, here plays a character who suggests in many respects Téchiné’s former mentor, the late Roland Barthes, a wistfully melancholic academic who wrote about many of Téchiné’s films and who appeared briefly as William Makepeace Thackeray in The Bronte Sisters. (Barthes’ book Fragments: A Lover’s Discourse often seems echoed in Marie’s rueful and amorous reflections about her former student, whose tape-recorded autobiographical musings form the basis of a book Marie writes. Even the title of a previous book she wrote, Traces, has a Barthesian ring.)

The gentleness of Marie’s physical relation to Juliette — revealed mainly in a scene where the two women take a bath together (and where Marie’s split-second, troubled glance at herself in a mirror while speaking is a perfect example of Deneuve’s actorly skill) — is contrasted with the brutality and mutual enmity contained in Juliette’s sex with Alex, which the film is equally candid about (and which Auteuil is no less adept at illustrating). American critics who glibly account for the alleged decline of European cinema by citing the increased sexual explicitness of American films can’t possibly be thinking of anything like Thieves, where characters like Marie, Alex, and Juliette and their sexual behavior are worlds apart from anything one could expect to find in American movies — and not because such characters and behavior are in any way absent from American life. (The film’s frankness about hatred and passion between family members, lovers, and even acquaintances gives its emotional texture a kind of turbulence that even a grandstander like Shine can’t approximate.)

The problem is acceptable canons. The European cinema presumed to be in decline is confined to the handful of titles bandied about in the mass media — the tiny fraction of European productions mainstream critics are equipped or willing to acknowledge. Thieves may be a dark and disturbing film, but it certainly isn’t an inaccessible one. Yet a good many mainstream critics would probably prefer not to deal with its emotional challenges and intricacies — which might force them to rejiggle their definition and estimation of European movies. This masterpiece is a particularly telling example of the kind of richness that is factored out of their reckoning, because it grapples with life in a way that often seems to be the exclusive preserve of literature.