From the Chicago Reader (February 16, 1996). — J.R.

My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud

Directed by Gerard Mordillat

Written by Mordillat and Jerome Prieur

With Sami Frey, Marc Barbe, Julie Jezequel, Valerie Jeannet, and Charlotte Valandrey.

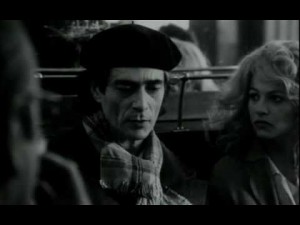

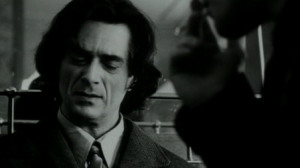

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel. Artaud’s circle has been lightly sketched, including such figures as the literary critic Marthe Robert. But the film reverses our expectations of how history is to be represented. Every “objective” historical (as opposed to personal) event related to Artaud — four scenes in all, beginning with his arrival in Paris and ending with his funeral — is depicted in a grainy, hand-held, highly mobile pseudodocumentary camera style distinctly different from everything else in the film. Seemingly shot in Super-8, these dreamlike, impressionistic sequences, mainly rendered without sound, are heady reminders of how intangible history, as opposed to imaginative speculation, usually is.

Gerard Mordillat’s 1993 French feature My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud, showing this week at the Music Box, can be regarded only nominally as a biopic. Adapted from the diary of an obscure poet, En compagnie d’Antonin Artaud (which is also the film’s original, superior title), it tells the story of the poet’s relationship with Artaud over a two-year period, from May 1946 to March 1948, when Artaud died at the age of 52. In 1946 Artaud had just returned to Paris after nine years in an insane asylum, and Jacques Prevel befriended him and procured drugs for him, mainly laudanum, opium, and chloral. But the film has relatively little to say about Artaud’s work, except in passing, and virtually nothing about Prevel’s writing apart from his diary. Shot in beautiful, crisp high-contrast black and white, the movie certainly has something to do with the “life and times” of this bohemian duo — and Sami Frey and Marc Barbe do creditable jobs as Artaud and Prevel. Artaud’s circle has been lightly sketched, including such figures as the literary critic Marthe Robert. But the film reverses our expectations of how history is to be represented. Every “objective” historical (as opposed to personal) event related to Artaud — four scenes in all, beginning with his arrival in Paris and ending with his funeral — is depicted in a grainy, hand-held, highly mobile pseudodocumentary camera style distinctly different from everything else in the film. Seemingly shot in Super-8, these dreamlike, impressionistic sequences, mainly rendered without sound, are heady reminders of how intangible history, as opposed to imaginative speculation, usually is.

In point of fact, My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud represents only one half of a dialectic about history; the other half has been cut off by U.S. marketing strategies. Just before making this feature, the writer-director and cowriter, Mordillat and Jerome Prieur, made a feature-length talking-head documentary about the same period of Artaud’s life, Le retour d’Artaud (“Artaud’s Return”) — a documentary that one critic has compared in its methodology to both Shoah and Francois Truffaut: Stolen Portraits. The Artaud documentary isn’t being distributed in the United States, so the press materials for the fictionalized version tend to glide over it. But chances are that if we saw the two films back to back, My Life and Times would have much more to say to us; a couple of years ago the two films were broadcast on France’s Arte channel only a few days apart. Still, My Life and Times has plenty to say about French culture (and our own by contrast) with or without an elaborate cultural context. A few basic questions, however, are worth answering.

First and foremost, who was Antonin Artaud? Here’s the short answer, from The Reader’s Encyclopedia: “French dramatic theorist and producer. Artaud influenced many playwrights by urging that the theater should translate experience into universal and primitive images, as explained in The Theater of Cruelty (1935) and The Theater and Its Double (1938).” He wrote voluminously on diverse subjects, and between 1924 and 1935 he worked on 22 films, mainly as an actor (in Gance’s Napoleon, L’Herbier’s L’argent, Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, and Lang’s Liliom, among others) but also as a writer: Artaud scripted one of the most famous French experimental films of the 20s, Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell and the Clergyman. Susan Sontag’s 43-page introduction to her edition of Artaud’s work is also helpful: Selected Writings includes poems, essays, letters, and one of his many unrealized screenplays.

Sontag notes that Artaud’s writings from 1946 to 1948 are “virtually unclassifiable as to genre: there are ‘letters’ that are ‘poems’ that are ‘essays’ that are ‘dramatic monologues’ — [giving] the impression of a man attempting to step out of his own skin. Passages of clear, if hectic, argument alternate with passages in which words are treated primarily as material (sound): they have a magical value. (Attention to the sound and shape of words, as distinct from their meaning, is an element of the Cabalistic teaching of the Zohar, which Artaud had studied in the 1930s.)” Interestingly enough, this distinction also seems to apply to Mordillat’s film, composed primarily of “clear, if hectic” fictionalized scenes interspersed with the “magical” segments dealing with historical events (some of which recall the stylized interludes in David Lynch’s The Elephant Man).

Not to put too fine a point on it, Artaud could also be described, especially during this period, as a raving lunatic — a lunatic of brilliance and vision to be sure, but a lunatic nonetheless, someone whose paranoid delusions couldn’t be separated from his manic creativity. And this fact winds up counting for more in Mordillat’s film in some ways than Artaud’s artistic legacy. (The same might be said for the German documentary about model-actress-composer-singer Nico called Nico Icon, which also recently played at the Music Box. But there the absence of any human identity for the film’s subject seems more an inadvertent offshoot of its superstar approach — including the way various self-promoters who barely knew Nico sound off about her inner soul and existential essence.)

About Jacques Prevel I know only that he wrote poetry, had a wife and a mistress simultaneously, befriended and procured drugs for Artaud (who read and commented on his poems), and suffered from tuberculosis. In the 661 pages of the Selected Writings I could find only one reference to him, by an editor, as a “new friend” and “young poet” who was the recipient of a letter from Artaud “against the cabala” written in June 1947, published after Artaud’s death but not included in the Selected Writings. This suggests that his diaries may have been published only after Sontag’s 1976 collection came out. (The first words we hear in the film after the credits is an entry from Prevel’s diary: “May 1. Artaud wrote me a long letter. If I could publish it, I would be saved. But I haven’t the money to go visit him at the Rodez asylum. Jany [Prevel’s mistress] has nothing either.” Much later we learn that Artaud specifically requested that Prevel not publish any of his letters — including one that could have served as a preface to a volume of Prevel’s poetry.)

Regarding Mordillat, I only know from the press materials that he was born in Paris in 1949 and has directed 16 short films and features since 1978, most of them for television; the most recent one cited, also made in 1993, is called Jacques Prevel, de colere et de haine (“Jacques Prevel, on Anger and Hatred”), clearly another spin-off of the Prevel diaries. Mordillat has also written “five books of various sorts” whose French titles reveal virtually nothing about them. About Prieur I can say a little more, because I own a rather good 1980 collection of his film criticism, Nuits blanches (“White Nights”), that includes an essay on “Artaud and the Cinema”; the book’s jacket informs me that Prieur was born in Paris in 1951, writes on film and literature, and is — or was — the film critic for La nouvelle revue francaise.

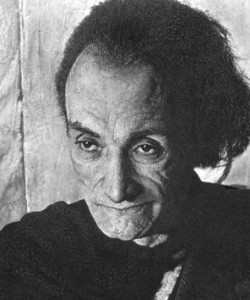

Sami Frey, who plays Artaud, is a wonderfully skilled French actor best known as one of the two leads in Godard’s 1964 Bande a part (“Band of Outsiders”); though it flopped commercially, both in France and the United States, it’s the French New Wave film that has most influenced American independent filmmakers, especially Jim Jarmusch, Mark Rappaport, Hal Hartley, and even Quentin Tarantino (whose production company, Band Apart, is named after it). Frey also appeared in Cleo From 5 to 7 (1962), Cesar and Rosalie (1972), The Little Drummer Girl (1984), Family Life (1985), Black Widow (1986), and Off Season (1992). Early in Frey’s career it was often remarked that he resembled the young Franz Kafka, so it seems appropriate that he should eventually be cast as another tormented European artist-martyr-seer whose work survives mainly in fragments. The difference is that Kafka didn’t live long enough to outlast his physical beauty, while Artaud did to an alarming extent; it’s quite a shock to pass from what he looks like in The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927) to photographs of him in the late 40s, which are enough to frighten small children. For all Frey’s gifts — including the remarkable capacity to make Artaud’s craziest lines ring with apocalyptic conviction — the still-handsome actor offers a considerably streamlined version of the lunatic writer.

It’s hard not to regard most of My Life and Times With Antonin Artaud as a deadpan comedy about the preternatural French tolerance for and even adoration of selfish, doomed, impossible artists. What’s difficult to know is whether the comedy is intentional, though given the overall intelligence of the script and direction I’m fairly sure it is. Indeed, what impresses me most about the film is its fearless and often hilarious depiction of what French culture, with its love of art and the mind, is willing to put up with in deranged artists. Consider the following exchange. Artaud: “Monsieur Prevel, I must tell you a secret. Don’t tell anyone. All the opium in Paris must be at Artaud’s disposal so he can finish his work. Only then will I recover my strength so I can help you. Think of that very hard, so it happens.” Prevel: “I already have, Monsieur Artaud.”

This tolerance is all the more striking because the film presents Prevel as well as Artaud as unbearable individuals. We see and hear Artaud brutally browbeat a member of his circle, Colette Thomas (Charlotte Valandrey), while directing her in the delivery of his text (one of the film’s “historical” events); he also provides a steady stream of solemn, solipsistic pronouncements. While staying in the Prevels’ apartment, he barges into the couple’s bedroom at 6 AM asking Jacques’ wife (Valerie Jeannet) where Jacques is, then asking why she’s still in bed. “It’s very early, Monsieur Artaud,” she sweetly explains, “and I’m pregnant.” “Don’t have a child, Madame Prevel,” he tells her. “Each time a child is born, it drains blood from my heart.” A bit later he informs Jacques, “Each and every time a man and woman have sex, I feel it. They deprive me, Antonin Artaud, of something.” And still later, explaining why he considers the life of Prevel’s mistress “useless,” he says, “Seven or eight million people need to be annihilated.”

If this attitude sounds a little over the top, the supposedly sane and clearly much less talented and interesting Prevel is equally outlandish, especially when it comes to oafish, self-centered behavior toward his wife and his mistress, again in the name of art. (One outraged Village Voice critic has attacked the movie for its sexism, which is rather like reproaching Central Park for its grass. She implies that a politically correct Prevel and Artaud would have improved the film, ignoring that this revision would also eliminate the movie’s raison d’etre and its historical verisimilitude.) Writing compulsively in his diary, even when his understandably fed up wife is screaming at him, Prevel observes that he’s not doing this for himself but for future generations (i.e., us), so everyone will understand just how remarkable Artaud was. When Prevel isn’t sitting at the great man’s feet or scribbling in his cahier, we see him popping pills, copping laudanum, coughing horribly, smoking incessantly, getting his mistress to phone her parents for more money, reviving her from a drug-induced coma with a splash of water from the sink so that he can have sex with her (capping a succession of scenes in her hotel room where the sink oddly figures as the hub of the room’s minimal activities), cadging a free ticket and a cigarette from another literary groupie outside a fund-raising event designed to help Artaud (another of the four “historical” events), and in general behaving exactly the way all cadaverous, depraved French poets are expected to.

To the picture’s credit, it has all the codes of this “artistic” behavior precisely mapped out, providing a morbid yet romantic portrait of the things that people are willing to do to one another as well as themselves in the name of art, neatly foreshadowed in the words of a torchy blues sung by an American singer (Liz McComb) at the beginning of the movie. If an equivalent deadpan comedy were ever made about this country’s madness, I suppose the emphasis would have to be different: the things people are willing to do to themselves and one another for the sake of sports events, cars, and other forms of light entertainment. For better and for worse, the French dementia is more metaphysical, even ghoulish — which is perhaps why this movie makes one so aware of the skeletons lurking inside the flesh of all the major characters.