From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1995). — J.R.

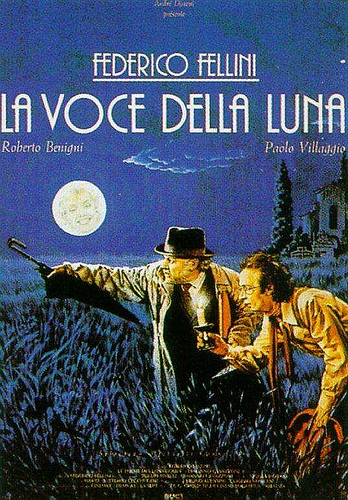

The Voice of the Moon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, and Ermanno Cavazzoni

With Roberto Benigni, Paolo Villaggio, Nadia Ottaviani, Marisa Tomasi, and Angelo Orlando.

Casino

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese

With Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone, Joe Pesci, James Woods, Don Rickles, Alan King, Kevin Pollak, and L.Q. Jones.

If I had the choice of seeing either Martin Scorsese’s latest (Casino) or Federico Fellini’s last (The Voice of the Moon) a second time, I’d opt for the Fellini. Both films are relatively minor works by relatively major filmmakers, though Scorsese has described The Voice of the Moon as one of Fellini’s “better pictures.” But Fellini’s swan song has a sweetness and sadness because it represents a kind of local — that is to say national — filmmaking that seems to be quickly vanishing from the mainstream. It isn’t hard to understand why no U.S. distributor has picked up this 1990 movie: it’s too Italian, and it isn’t at all easy to follow as storytelling, because it digresses all over the place. Yet these qualities, which are part of the film’s charm and poetry, might have worked in its favor outside Italy 30 years ago, when audiences tended to be more curious about other cultures and other forms of storytelling.

I don’t know how well The Voice of the Moon did in Italy, but it opened in 200 theaters, and the fact that the two lead actors, Roberto Benigni and Paolo Villaggio, are popular Italian comics undoubtedly helped draw people in. Yet we all know that Casino will take in more money — not because people will like it more (something I tend to doubt), but because it cost a lot more, and Universal wants to get its money back. People all over the world will see it because of the names connected with it — especially Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone, and Scorsese — and they probably won’t regard it as being “too American.” Chances are they won’t think too much about it being American at all, just as McDonald’s hamburgers aren’t perceived as American to the degree they used to be: they’re too familiar to be exotic. My guess is that the folks in Hong Kong who see Casino will care almost as little about what it says about American life — its only artistic excuse, assuming it has one — as most American fans of Hong Kong action movies care about Chinese life.

My predecessor at the Reader, Dave Kehr, wasn’t very sympathetic to Fellini — or to Ingmar Bergman or Woody Allen — during his 11 years at the paper, and because I usually share these biases I’ve often retained his unfavorable capsule reviews of their pictures in our Section Two listings. My antipathy comes largely from the outsize reputations of all three filmmakers given their narrow thematic and stylistic ranges — especially in the case of Allen, whose dogged reliance on Bergman and Fellini is probably his biggest shortcoming. Bergman and Fellini have also seemed overrated because their defenders have usually shortchanged more substantial and ambitious figures like Dreyer, Rossellini, and Antonioni. If Bergman and Fellini were the best cinema could offer as art (Allen’s watchword), by implication artists who accomplished or even attempted more were overreachers. I readily concede that Bergman and Fellini are important, but I wouldn’t want to be a film critic if I thought that Bergman’s neurotic, antiseptic psychodramas and Fellini’s cartoon surrealist spectacles were the best movies can do — especially since both artists tended to repeat themselves ad infinitum (with noble exceptions, such as Persona and 8 1/2).

This was the gist of my demurral — and, if I’m not mistaken, Kehr’s — for most of the 60s, 70s, and 80s. But once Bergman retired from filmmaking and Fellini’s work stopped getting U.S. distribution, I began wondering whether their oeuvres were getting their proper due. Bergman’s last major film, Fanny and Alexander, has to the best of my knowledge never been shown here in its five-hour version — the only version Bergman recognizes as his own, but one that was excluded from a supposedly definitive Bergman retrospective held recently in New York. The declining interest in distributing Fellini’s late work here has also been distressing.

As Orson Welles once suggested, Fellini’s strengths and limitations have always been those of a wide-eyed country bumpkin in the big city. Early in his career he was able to draw on his provincial as well as urban experiences to recount extended stories, the best of which were probably The White Sheik and I vitelloni in the early 50s and La dolce vita and 8 1/2 in the early 60s. (It’s been too long since I’ve seen the intervening vehicles for his actress wife Giulietta Masina, La strada and Nights of Cabiria, to judge whether they survive their sentimentality.) But after 8 1/2 Fellini’s sense of narrative disintegrated into a kind of conveyor-belt spectacle, highlighting one damn showstopper after another — sometimes with brilliant moments and interludes (as in his Roma and Amarcord), sometimes with memorably disturbing undertones (as in his Satyricon and Casanova). But these films were invariably rather shapeless freight trains, going nowhere in particular except across the screen. “Fellini” had begun to seem undifferentiated; like pepperoni it could be sliced into at any point.

The Voice of the Moon differs somewhat from this formula in being the first Fellini film since Satyricon adapted (however freely) from a novel, Ermanno Cavazzoni’s Poems of a Lunatic. But it also might be said to fit the formula insofar as Fellini improvised the script day by day. Apparently the main inspiration provided by the novel was its poetic handling of the countryside — which Fellini associated with his grandmother’s village near Rimini, a place he visited in the summers as a boy–and Fellini reportedly built an entire village square before mapping out any of the action or dialogue. He deliberately made this village geographically imprecise and had the characters speak a variety of dialects — something pretty uncommon in Italian cinema, where movies tend to get redubbed in dialect for different regions — but the overall ambience is certainly Italian. The film’s visual organization perhaps owes more to lyrical poetry than to narrative prose, at least in the excuses it uses for getting from one thing to another.

Faint whispers can be heard behind the film’s credits, and the alluring opening shows Salvini (Benigni) in a misty countryside at night, peering down a well and noting that the voices are calling to him. A few other local males turn up, and shortly afterward we see them all spying through a window at a plump woman dancing alone and stripping. The relation between looking down a well and looking through a window becomes one poetic cluster of images, and when Salvini later gazes at the moon and identifies it with a woman named Aldina (Nadia Ottaviani), this becomes a second cluster that rhymes with the first. By this time we’ve also been introduced to a village prefect (Villaggio) who figures in some of the visual clusters as well. (I can’t comment on Fellini’s use of this actor, but he makes Benigni’s comic persona much quieter and meeker than usual, reminding me of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s apt remark in a 1960 essay: “Fellini always uses actors in a way that is extravagant, unexpected, and in a way that radically violates and forces a total reinvention of their film personalities.”)

It’s difficult to assign a plot to most of what follows, but there’s a stretch of magical realism in the four notes played on an oboe that cause furniture to move (as well as in some poetic reveries about the relation between music and fire), and there’s a bit where Salvini speaks to the dead in a cemetery, and a beautiful bit where he’s rescued from a rainstorm by an old woman, who takes him to a cottage whose interior recalls the harem/bath scene in 8 1/2. Things more or less culminate in an extended beauty pageant held in the village squaren– not a sequence that equals the wedding party at the end of Amarcord, but a lovely conclusion to Fellini’s career nevertheless. It’s also a whiff of something precious that’s now on the verge of extinction because publicists don’t know how to peddle it to the mass market. (That’s why The Voice of the Moon is showing only twice this year in Chicago, while Casino is showing more than 120 times this week alone, not counting the suburbs.) To accept this gorgeous, archaic coda you have to go along with the premise that the moon is not only female but Italian. How much easier it is, apparently, to go along with the premise that success is a boring, insensitive man in a bright pink jacket.

The first and best of Casino‘s three hours is dominated by an intricate piece of exposition — narrated alternately by Sam “Ace” Rothstein (De Niro, the man in the pink jacket, a bookie appointed by the midwest mob to run four casinos) and Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci, Rothstein’s friend and hit man) — about the way the Las Vegas casino business worked between 1973 and 1983. None of this is very fresh or interesting as a subject, though it’s promising as a form of narration, with Sam and Nicky’s voices occasionally interacting, and Scorsese’s usual flurry of hyped-up camera moves jiggling the visual accompaniment like a cocktail shaker. But then the air slowly leaks out of this vehicle’s tires, and we’re left with a story we’ve heard many times before and with familiar characters who are even less interesting than usual.

Dramatically Casino is like an almost random anthology of moments from other Scorsese-De Niro pictures, a dehydrated summary of past glories that gives us no indication why we’re supposed to care about any of these people. Even the violence here lacks the passion of equivalent moments in Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, and at one point the picture descends to using Georges Delerue’s melancholy main theme from Godard’s 1963 Contempt to express a man’s estrangement from his wife, which becomes a kind of rented expressiveness rather than an emotional investment or discovery.

That Scorsese manages to make all this watchable even when it isn’t interesting (which for me was most of the time) is a tribute to his gifts as an entertainer, and these gifts shouldn’t be sneezed at, for this is a professional piece of filmmaking compared to most other recent studio releases. But don’t look for anything passing for poetry here — apart from a few verbal riffs about holes in the desert surrounding Las Vegas that are closer to being nasty jokes.

At most we get the splendid star presence and intelligence of Sharon Stone, even in the thankless role of a pathetic character — a local hooker named Ginger McKenna who makes the mistake of marrying Rothstein — with no surprises and little evidence of any inner life. Not that Rothstein or Santoro can claim an inner life, but Stone has the advantage of not having appeared in any previous Scorsese movies, which gives her a freshness De Niro and Pesci couldn’t buy with their salaries. Even after you figure in all the differences in locale and economic level and period between GoodFellas and this movie, these two are still doing basically the same shtick, with the same screenwriter (Nicholas Pileggi), to lesser effect. (Pesci gets in a few odd moments with Stone, but that’s about it.)

A friend who likes this movie (and all other Scorsese movies, for that matter) tells me it’s about what money and power do to people — as if we hadn’t heard that song before. It’s certainly about what money and power have done to movies. But now that dreary and unimaginative executives are setting most of our cultural agenda, buying “style” from able courtiers like Scorsese, do we have to sit still for dreary and unimaginative movies about these deadbeats?