From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1995). — J.R.

Beyond Rangoon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by John Boorman

Written by Alex Lasker and Bill Rubenstein

With Patricia Arquette, U Aung Ko, Frances McDormand, Spalding Gray, Tiara Jacquelina, and Victor Slezak.

Reviewing Salvador Dali’s autobiography half a century ago, George Orwell wrote that Dali “grew up in the corrupt world of the 1920s, when sophistication was immensely widespread and every European capital swarmed with aristocrats and rentiers who had given up sport and politics and taken to patronizing the arts. If you threw dead donkeys at people, they threw money back.” Offended by the sort of sophistication that he associated with mindless tolerance, Orwell recorded his own puritanical outrage at the brutal shenanigans of Dali and his apologists: “It will be seen that what the defenders of Dali are claiming is a kind of benefit of clergy. The artist is to be exempt from the moral laws that are binding on ordinary people. Just pronounce the magic word ‘art’ and everything is OK. Rotting corpses with snails crawling over them are OK; kicking little girls on the head is OK; even a film like L’age d’or is OK.”

Unfortunately, Orwell hadn’t seen Buñuel’s 1930 masterpiece and had been misinformed about it; it’s subsequently been demonstrated that, contrary to popular belief, Dali had little to do with it. Moreover, Buñuel’s film has held up remarkably well. But if you substitute “businessman” for “artist” and “business” for “art” in the rest of Orwell’s diatribe, you come pretty close to describing the kind of mindless tolerance that defines sophistication in the corrupt world of the 90s.

If, once upon a time, audiences would throw money at artists who threw dead donkeys at them — a trend that, according to some opponents of the National Endowment for the Arts, has survived until fairly recent cutbacks — today we’re prone to praise and reward businesspeople for insulting us, often by throwing remakes at us. It’s arguably an insult to Robert Rodriguez as well as his public to hire him to do a big-budget remake of his own low-budget El mariachi, which ran in commercial theaters only two years ago and made a strong impression on audiences. But that’s what Columbia Pictures has done in the recent Desperado, and most mainstream critics don’t seem to mind a bit; they even go out of their way to excuse the film, explaining that it’s half remake and half sequel anyway, so what the hell? (Sequels too are just giving the idiot public more of what it wants.) After all, goes the implicit argument, if Columbia Pictures can make more money by treating us all like jerks, more power to them.

Consequently we have no business complaining when a big-budget version of another low-budget hit — The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, released only a year ago — opens in a week, courtesy of artistic visionary Steven Spielberg, who apparently decided it was time for his production company to do for drag queens what he personally has done for blacks in The Color Purple, war refugees in Empire of the Sun, and Jews in Schindler’s List. As savvy as congressional lobbyists, the distributors are carefully not mentioning The Adventures of Priscilla in any of their press materials and are even asserting that To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar is “based on an original screenplay.” Maybe they’re right, but one can only wonder how it happens that two road movies about three drag queens going on a transcontinental journey and enlightening the straight population are appearing in such close proximity. Given how much obfuscation is routinely involved on the script credits for big-budget movies, one might say we expect the studios to lie, and expect most reviewers and journalists to parrot the disinformation; after all, make-believe is what Hollywood’s all about.

Insults of this kind are relatively mild, one might say, since they depend on how much we keep up with current movies and relate simply to movies’ generally shopworn materials. But what about the insulting assumption that Americans are incapable of caring about anyone in the world except themselves? We may be less likely to notice this kind of insult because it’s usually more indirect — part of the concept, built into scripts, ads, and marketing schemes (assuming one can distinguish among the three). But such assumptions are an important part of certain movies nevertheless, and to respond to these movies in the intended way is ultimately to agree to be insulted by them.

A case in point is Beyond Rangoon, an exotic action-adventure movie directed by John Boorman (as an assignment, not a project of his own): it provides plenty of entertainment as long as you can overlook the fact that it’s implicitly treating you like a greenhorn dunderhead. The first time I saw it, in Paris three months ago, it was easy for me to overlook these insults because I’d consumed half a bottle of wine and was more or less on a reviewer’s holiday. I only faintly recalled Vincent Ostria’s warning in Cahiers du Cinéma that this was “the most shameful film of Boorman’s to date.” (“One had the impression that John Boorman had reached a serious impasse [in his career]. But one didn’t believe he was desperate enough to plunge into the realization of a pure American potboiler.”) The fact that I nodded off for 15 minutes or so toward the end hardly seemed to matter; this was merely an attractively filmed third-world romp with nicely paced suspense sequences and gorgeous landscapes. Boorman handles ‘Scope compositions better than any current American director I can think of, and the action shots are managed much more fleetly than any of the shoot-outs in Desperado, for example. But I can’t really argue that what I was watching was substantially different from a comic strip like Terry and the Pirates.

It might seem a little heartless to describe in this fashion a movie that purports to be giving us the lowdown on the wholesale slaughter of innocent students and others protesting government oppression in 1988 in Burma (a country currently known as Myanmar). Indeed, an opening title states, “This film is inspired by actual events,” and a closing title — no longer quite up-to-date, I’m told — describes the progress of Aung San Suu Kyi and her Democratic party since 1988, including her being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991. But the political information we’re given in between these two titles is limited and filtered through the consciousness of a San Francisco tourist and doctor, Laura (Patricia Arquette), struggling to recover from a personal tragedy: her husband and little boy were both violently murdered. She also serves periodically as offscreen narrator. Laura clearly finds all the bloodshed and her spontaneous involvement in helping the victims therapeutic, and the implication is that without this therapy the brutal imposition of martial law, including torture and soldiers firing into crowds, wouldn’t matter so much, either to her or to us. Certainly the brutality doesn’t seem to matter much to Laura’s sister (Frances McDormand) or her American guide, a professor of Asian art (Spalding Gray): both of them take off for Bangkok early on. Laura has lost her passport, but they expect her to follow on the next plane: “This is a military dictatorship, in case you haven’t noticed,” Gray helpfully points out to her and to us.

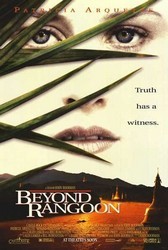

Given the basic story, it’s a bit dishonest, or at least misleading, for the movie to begin, “This film is inspired by actual events,” implying that a real-live American doctor who lost her husband and son overcame her grief and her aversion to the sight of blood by witnessing the massacres in Burma. All that the opening title really means by “actual events” are the massacres themselves, which the movie doesn’t treat as important enough to attract our interest without Laura’s validating presence. One of the ads for Beyond Rangoon says it all: “Truth has a witness” is the headline, as Arquette’s giant white features hover over an aerial view of a picturesque Burmese landscape about one quarter as large as her face. In other words, truth requires an American movie star; native witnesses aren’t enough.

Candor compels me to admit that the second time I saw Beyond Rangoon I was once again entertained by Boorman’s gift for handling action, framing landscapes, and telling a story — even though it’s a formulaic, simplistic story in Alex Lasker and Bill Rubenstein’s script, with no interesting or developed characters to speak of. I didn’t know any more about the situation in Burma/Myanmar than I had three months earlier; nothing about seeing the movie the first time, including its self-righteous denunciation of human-rights violations, had encouraged me to brush up on the subject. That’s one of the consequences of keeping the story and the political background as simplistic as they are here; there’s just enough about the students for us to feel paternalistic toward them, and just enough about Laura’s guide, a former professor (engagingly played by a nonprofessional, U Aung Ko), for us to accept a few adages about Asians taking suffering for granted. In short, we only need a bit of Asian suffering and Buddhist wisdom to accept the premise of Laura gaining some sense of purpose from her decorative and energizing surroundings. Any more information and her story would lose its impact, and consequently our interest in the Burmese characters would decrease.

Watching Beyond Rangoon a second time, I was entertained and insulted in about equal proportions. The movie artfully appeals to some of the more hypocritical parts of my liberal conscience and gives them a gentle workout, but it doesn’t really change anything — except the bank accounts of a few studio executives, which is all that really matters anyway. What dead donkeys were for Dali, dead Burmese are for Castle Rock Entertainment; throw enough of them at the audience, and if you take care to toss in Patricia Arquette, people will be sure to throw money back.