From the Chicago Reader (November 18, 1994). — J.R.

You can figure out a lot about the differences between our culture and French culture by comparing two current series of low-budget TV features about teenagers. The French series, Tous les garcons et les filles de leur age (“All the Boys and Girls of Their Age”), produced by the French “cultural” channel Arte, has yielded half a dozen features, most of them first-rate. The idea is for the filmmaker to make a fictionalized version of his or her own teenage years set in the appropriate period (different in each film) and to include at least one party scene in which pop songs of that era are used. (The series is financed in part by Polygram, which has furnished the appropriate recordings.) The first of these, Patricia Mazuy’s Travolta and Me, showed at last year’s Chicago International Film Festival; four others were programmed at the festival last month — Olivier Assayas’ Cold Water, André Téchiné’s Wild Reeds, Cedric Kahn’s Too Much Happiness, and Chantal Akerman’s Portrait of a Young Girl From Brussels — but unfortunately the first and best of these was canceled at the last minute. One more, Claire Denis’ Boom Boom [later retitled U.S. Go Home], has also been completed.

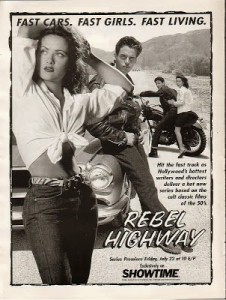

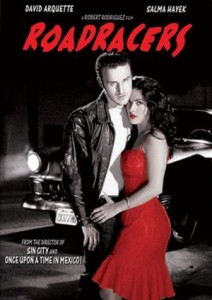

The American series is Rebel Highway, also known as “Drive-In Classics.” Showtime started to run it on cable TV last month, and it will continue for many weeks to come in weekly double features. This series consists of ten “remakes” (or, more precisely, reimaginings) of ten teenage exploitation features released by American International Pictures in the 1950s, assigned to ten different directors. With the exception of Robert Rodriguez — the young filmmaker who made last year’s El mariachi, and whose “remake” of Roadracers has been described to me as one of the most striking films in the series — all the directors are old enough to have been alive during the 50s. Each was given a budget of $1.3 million, a 12-day shooting schedule (i.e., two six-day weeks), and the same technical crew, to correspond roughly with the manner in which the originals were made but with allowances for inflation. The directors also had the right to a final cut, as well as the right to select the screenwriter, the director of photography, and the editor — luxuries none of the original directors had. Like the French series, all the American films make extensive use of period pop songs.

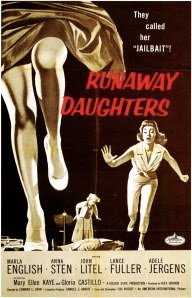

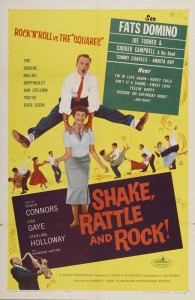

Among the Rebel Highway films to have run so far are John McNaughton’s Girls in Prison, Joe Dante’s Runaway Daughters, Mary Lambert’s Dragstrip Girl, Allan Arkush’s Shake, Rattle and Rock!, and Rodriguez’s Roadracers, which I haven’t seen; the ones still to come are William Friedkin’s Jailbreakers, John Milius’s Motorcycle Gang [see still below], Uli Edel’s Confessions of a Sorority Girl, Ralph Bakshi’s The Cool and the Crazy, and Jonathan Kaplan’s Reform School Girls. Most of the originals are hard to come by these days, and I can’t remember for sure which ones I saw in the 50s. But if distant memories are to be trusted, the originals were distinctive only in their utter lack of distinction, unlike many of the AIP pictures made by Roger Corman; the four remakes I’ve seen were all of films originally directed by the routinely anonymous Edward L. Cahn.

One obvious difference between the two series is that the French films are semiautobiographical reflections while the American films are spin-offs of previous genre product. The French films are introverted, the American extroverted: the French directors were invited to think about their own lives, while the Americans had to start with schlocky movies virtually defined by their tossed-off, ephemeral quality. Not surprisingly, given the special feeling in the French cinema for adolescence, that series has already yielded rather spectacular results, including the best work I’ve seen by Assayas and Téchiné (though regrettably these are not the sort of pictures American distributors have shown any interest in picking up). The American series, on the other hand, is at best a collection of offbeat so-called B-films, though given the state of American movies at the moment this is a much more sizable achievement than it might at first appear — especially considering that the whole system that once supported B-films no longer exists. Indeed, from one point of view the term “B-film” as it’s currently used is as much a misnomer as “sneak preview” — another term that refers misleadingly to a practice that no longer exists. (A “sneak preview” originally meant a preview of an upcoming feature whose title was unannounced, shown on a double bill with a current feature in order to poll audience reactions. Current previews, however, advertise their titles and are generally meant to foster “advance buzz” or word of mouth. The only thing sneaky about them is the misleading use of the term “sneak.”)

A long-out-of-print 1975 collection edited by Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, Kings of the Bs, contains invaluable information about the evolution and demise of B-films. The editors note that the whole concept was predicated on a virtually guaranteed audience: by the end of the 30s, they note, weekly movie attendance was 75 million, and when it peaked in 1946, it was around 100 million, a staggering two-thirds of the American population. (By the late 60s and early 70s, the weekly numbers had decreased to about 20 million.) Moreover, from 1935 to around 1950, American moviegoers expected a double feature (as well as a cartoon, a newsreel, and trailers) every time they went to the movies; by the mid-30s this was the fare at 85 percent of the movie houses. During this period, “A” features were the big-studio productions with stars, booked by theaters on a percentage basis (with the larger percentage of the receipts going to the distributor), and “B” features were cheaper, generally shorter films made at smaller studios, booked for a fixed rental fee to be paid by the exhibitors. By 1955, however — the year that American International Pictures was founded — the practice of combining an A and a B feature on a double bill was nearly defunct; in a 1974 interview the company’s founder, Samuel Z. Arkoff, noted that the term “B-movie” had no meaning even when AIP started. They turned out double features for the teenage market packaged to play together in theaters and drive-ins on a percentage basis; but in terms of the former system, apart from the fact that they were relatively short and cheaply made, none of these movies qualified as A’s or B’s. Prior to 1955, the teenage movie market didn’t exist because economically speaking — which in this country always means culturally speaking — the teenager didn’t exist. Only after the postwar boom were teenagers granted enough pocket money and autonomy to comprise a separate market; at that time rock and roll and drive-in double features came into their own, and with them a whole new strain in moviemaking and moviegoing. For virtually the first time, “bad” movies that teenagers could feel superior or at least equal to became a significant part of movie culture — a phenomenon quite distinct from the work of a schlockmeister like Edward D. Wood Jr., who started out in 1953 (with Glen or Glenda?) in the dregs of B productions and never progressed beyond them or into assembly-line operations like AIP. Consequently, a threadbare Wood opus like the 1959 Plan 9 From Outer Space never had anything like even the limited commercial cachet of an AIP opus like Corman’s Teenage Caveman, released the same year; only later generations, with their approximate grasp of film history and market distinctions, would call both of them B-movies. (By the same token, the naive “badness” of a Wood movie was worlds away from the more calculated and ironic “badness” of a Corman quickie, which had more of a predefined market.)

If an auteurist series like Tous les garcons et les filles de leur age suggests a continuity with the French cinema of the past, this is more a matter of the theme of adolescence, which we associate with some of the best early pictures of Truffaut and Godard, than of genre. But in this country, genre moviemaking has become the precondition of auteurist TV commissions — a fact as apparent in John Dahl’s The Last Seduction, originally made for and shown on HBO and receiving theatrical release in Chicago this week, as it is in Rebel Highway. Characteristically, a loose sense of genre — in this case, film noir — in The Last Seduction is supposed to justify attitudes that otherwise might not be ideologically palatable. About once a year, it seems, a movie featuring a ferociously evil and malicious bitch (or witch) is a huge hit with audiences, critics, or both, and each time it happens — as in Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct, or Dahl’s Last Seduction — some version of noir styling helps make this demonology acceptable; often such styling even takes the place of character motivation. In effect, this idea has been imposed on the past in order to excuse the present: during the heyday of noir in the 40s and 50s, when bitch heroines were a dime a dozen, nobody in this country used or needed or even thought of the term “noir” to justify them, but today the term is used as a form of retroactive validation. (Another form of validation is calling these recent films “feminist” because they portray “strong women”– an argument that’s usually put forward by men and that generally ignores how patriarchal the movie’s underpinnings are.) Similarly, an artificial, ahistorical notion of the B-movie is the necessary prop for Rebel Highway, the implication being, as with “sneak previews” and “noir” films, that Hollywood history has an unbroken continuity. But if this concept is somewhat bogus, it’s also what gives the series an undeniable interest. Back in the 50s, Hollywood movies broached serious social and political issues a good deal more often than TV dramas of the time did, though AIP systematically steered clear of them. Today that situation is virtually reversed, and the Rebel Highway movies capitalize on the difference by politicizing the AIP youth movies for the first time, “rewriting” and in effect correcting them in order to represent the social and political issues of the 50s more accurately. Indeed, Lou Arkoff — the son of AIP’s founder, and one of the series’s coproducers — sees it this way himself. As he put it in an interview with critic Bill Krohn, “Most of the movies about teens in the 50s weren’t honest, because of censorship, but now you can take directors who were there in the 50s and let them tell the stories.”

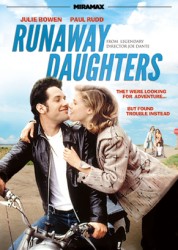

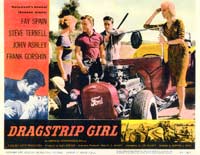

Seeking to avoid camp, the Rebel Highway movies aspire to a kind of historical revisionism, with fascinating if uneven results. On a conventional level the best of the four I’ve seen is Dante’s Runaway Daughters, the only one that plausibly captures the period in which it’s set — 1957, shortly after Sputnik went into orbit and the year after the original Runaway Daughters was made. Scripted by Dante’s usual writer, Charles Haas, the movie careens from an opening newsreel montage of 50s events to a double-date make-out session at a drive-in showing I Was a Teenage Werewolf. Eventually it focuses on three teenage girls who decide to run away after one of them becomes pregnant and her boyfriend takes off to join the Navy. (Sputnik figures significantly in both his seduction patter and his excuse for enlisting, and Corman and his wife put in cameos as his parents.) Hoping to intercept him in San Diego before he’s shipped off, the girls fake a kidnapping note, steal a car, and scratch off, heading south. Reportedly sticking closer to his source than most of the other series directors, Dante gives his material charm, wit, and verve by working gracefully with his likable cast (including such familiar faces as Joe Flaherty, Robert Picardo, Fabian, John Astin, and even Cathy Moriarty in an uncredited cameo). He seems wholly at ease with both the period and the AIP mode, both of which he affectionately parodies. A typical spin on the material comes when AIP (and Dante) regular Dick Miller, playing a private detective investigating the girls’ disappearance, lectures four of their parents: “Do you people ever sit down and talk to your kids? I mean really talk to them about sex and sexual diseases, about peculiar practices? About the strange night world of twisted kicks [an electronic instrument starts to warble on the sound track, evoking 50s SF movies], of weird rituals and equipment? Of whips and chains and rubber balls and dildos and handcuffs?” A little later, gazing at the poster for the original Runaway Daughters at a drive-in, Miller sighs, “Ah, they don’t make ’em like they used to” — Dante’s sentiments exactly. Perhaps one reason they don’t is a certain lost innocence; Dante seems to betray his own lost innocence just after the runaway girls discover that a couple of hunters wrongly suspected as kidnappers and shot by the cops were actually “mad-dog killers,” not innocent bystanders. Instantly the girls’ misery turns to joy, and their implied indifference to the deaths of the hunters and their victims as soon as their own responsibility is lifted sadly registers more as a 90s response than a 50s one. This is a rare lapse for Dante. But the illusion of being back in the 50s or in a 50s movie is never established to begin with in Girls in Prison, Shake, Rattle and Rock!, and Dragstrip Girl. What one gets instead are attitudes and ideas about the 50s — passionately engaged in the first two, conventional and rather dull in the third. Part of the problem is the tone struck in the scripts; because the filmmakers feel compelled to make up for the fact that people never swore or made racist remarks or took off their clothes in the originals, they usually lay these things on with a trowel here, and the characters wind up coming across as 90s archetypes in 90s movies.

In Dragstrip Girl, this is a matter of the Chicano hero’s Chicana girlfriend using the work “fuck” every chance she gets. I’m sure that some teenage girls in the 50s were perfectly capable of saying “fuck” to their boyfriends, but I doubt that any of them said it as often as people in 90s movies do. Similarly, I doubt that many 50s bikers read passages from On the Road aloud to one another, as a couple of them do in Shake, Rattle and Rock!, or that any 50s TV newscaster would come on the air saying, “Jim Jeffreys with 60 minutes of the world news — and it’s bad, damn bad,” as one does near the beginning of Girls in Prison. The latter gaffe actually came from the typewriter of the great, irrepressible Sam Fuller, who wrote the hyperbolically Fuller-esque script of Girls in Prison along with his wife, Christa Lang. This pulpy script is so evocative of hysterical, juicy Fuller movies like Shock Corridor and the 1989 Street of No Return (coming to the Film Center, belatedly, next month) that John McNaughton’s efficient direction seems secondary, even from an auteurist perspective. Thanks to the script, this movie is revisionist 50s with a vengeance, and a wild retort to much of the received wisdom about some of Fuller’s own 50s pictures, like Pickup on South Street; some people have unjustly labeled him a right-wing anticommunist ideologue.

It’s not an impression that can survive the beginning of Girls in Prison, where in rapid succession we see what landed each of the three teenage heroines in prison circa 1953, the same year Pickup on South Street was released. Communism is in fact dealt with only in the first two episodes. In the first, a black teenager named Melba (Bahni Turpin) sees the corpse of her enlisted brother in Korea on TV, then discovers her mother has died of a heart attack after watching the same live news broadcast; she goes to the studio where the xenophobic, red-baiting newscaster is still ranting and bashes his brains out with a hammer. In the second episode, a lesbian teenager named Carol (Ione Skye), who drafts an anti-McCarthy play called The Witch Hunt for her beloved and famous father to star in, witnesses a riot break out in the theater on opening night; when the dust settles, her father has become a raving lunatic who can only repeat over and over, “Are you a communist?” She reluctantly commits him to an insane asylum. Then, on a TV in a bar, she watches Joseph McCarthy browbeat a woman in the Screen Actors Guild with charges of communist activities (using former guild president Ronald Reagan to support his insinuations), which inspires some invective from the guy on the bar stool next to Carol about the “commie whore” and “pinko bastards”; with a howl of rage, she smashes the guy on the head with a bottle. All of this transpires in 10 minutes, and Fuller and Lang’s energy is such that the movie never really slows down or becomes any more reflective over the 73 minutes that remain. With a manic performance by Jon Polito as a record producer and the extensive use of a pop song about death, “Endless Sleep,” written by the third teenage heroine, the movie manages to remain delirious throughout its convoluted story. Impossible newspaper headlines periodically punctuate the action like chapter headings, and there are many other Fuller-esque conceits (for example, a striptease performed by female inmates in drag for the other female prisoners). It’s much too goofy to take as a straight 50s story, but as a fever dream about the 50s it beats any AIP original I can think of.

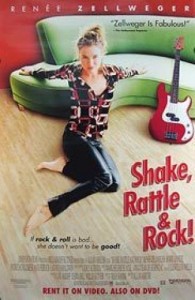

At certain moments and in its own way, Allan Arkush’s Shake, Rattle and Rock!, whose script is credited to someone named Trish Soodik, is equally frenetic, and its plot is every bit as politically committed. Of the four, this is the one that’s most attentive to black characters, routinely omitted in the original AIP quickies even when they would have had an immediate bearing on the story (as they do here). I was won over by the credit sequence, which shows rock-and-roll heroine Susan (Renee Zellweger) lip-synching Little Richard’s “The Girl Can’t Help It” while cavorting madly around her fluffy 50s bedroom, shot in a slurred, pixilated form that recalls the exuberant camera style of Wong Kar-wei (Days of Being Wild, Chungking Express). The movie charts the pitched battle between intolerant, racist antirock adults, led by a rabid ringleader (Mary Woronov) and including Susan’s mother (Nora Dunn), and Susan and her rock allies: Danny (Howie Mandel), who hosts an American Bandstand-style TV show; Cookie (Patricia Childress), Susan’s saxophone-playing best friend; a black female vocal quartet headed by Sireena (Latanyia Baldwin); and a drummer who provides them with a former Chinese restaurant to perform in.

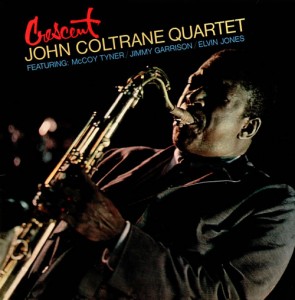

Though it’s worth pointing out that antiblack attitudes were behind some of the attacks on rock by white adults in the 50s, and that some white musicians (notably Gene Vincent) did fight interracial battles, this film still comes across mainly as a post-50s scenario superimposed on a 50s story — especially when it comes to Susan, Cookie, and Sireena, a teenage trio every bit as aggressive and potent as the ones in Runaway Daughters and Girls in Prison. Indeed, this movie’s sense of ethics is predicated on perceiving the 50s through the revisions and corrections of subsequent decades, from the point of view of the 60s counterculture to the feminism of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. (Interestingly, the only film in Tous les garcons et les filles de leur age comparably indifferent to precise period detail is Akerman’s lovely Portrait of a Young Girl From Brussels, which has a quasi-feminist agenda of its own: the heroine’s nascent lesbian longings in a period that largely precluded their definition or realization.) Anachronistically, the plot of Shake, Rattle and Rock! occasionally recalls John Waters’s Hairspray, set in the 60s: there another teenage TV dance show becomes the public forum for desegregation, whereas here rock and roll is literally placed on trial during a TV call-in show. There’s also a powerful moment in the closing scene when we hear a pastiche of John Coltrane’s gorgeous 1964 “Crescent” on the sound track. Dramatically and thematically, this anachronism works beautifully: Coltrane’s soulful jazz lament follows immediately after rock and roll is found guilty, and just before Susan decides to cast her lot with a disreputable biker and proto-beatnik. Postmodernism with a political edge, Shake, Rattle and Rock! is like an urgent message placed in a bottle, addressed not to the 50s but to the 90s; yet given who we are and what we want, it has to be routed through the 50s and 60s in order to reach us.