From the Chicago Reader (July 15, 1994). — J.R.

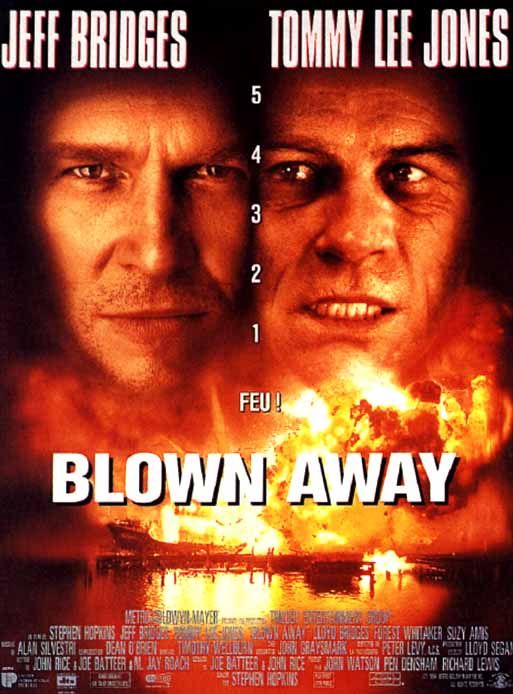

* BLOWN AWAY

(Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Stephen Hopkins

Written by Joe Batteer, John Rice, and M. Jay Roach

With Jeff Bridges, Tommy Lee Jones, Lloyd Bridges, Forest Whitaker, Suzy Amis, John Finn, and Stephi Lineburg.

In the Roy Rogers westerns I saw as a kid, I could always figure out in a flash who the villain was. If memory serves, Roy Rogers always played a cowboy named Roy Rogers, whom the good characters invariably called Roy and the bad guy referred to as Rogers. This sometimes made it possible to know who the bad guy was even before Roy figured it out himself.

There’s a popular kind of suspense movie that’s been with us at least since Dirty Harry in which the villain is often just as easy to detect: he or she is someone who has it in for the hero and wants to hurt him very, very badly, most often by hurting or killing whomever the hero is supposed to protect: his daughter’s pet rabbit (Fatal Attraction), his wife, his mistress, and his daughter (Cape Fear), the citizens of Gotham City (the Batman movies), the president of the United States (In the Line of Fire), the passengers in a local bus (Speed), a coworker and a pet dog and a wife and a daughter (Blown Away).

Unlike the villains in Roy Rogers movies, who were generally motivated by simple greed, these more twisted villains are bent on baroque revenge, which frequently takes the form of childish one-upmanship: ha ha ha, I’m better than you; you can’t catch me, asshole, let’s see you try. An even greater difference, however, and a much stranger one, is that whereas the old cowboy villains were plainly tailored to the worldviews of toddlers, many of the more recent villains are supposed to be geared to the tastes and outlooks of adults while still retaining the same simplistic motives — so that “ha ha ha, I’m better than you” is the cry not only of such cartoonish characters as Jack Nicholson’s Joker and Danny DeVito’s Penguin — villains originally designed for the predilection of kids — but also of allegedly sophisticated characters like Robert De Niro in Cape Fear, John Malkovich in In the Line of Fire, Dennis Hopper in Speed, and Tommy Lee Jones in Blown Away. (Significantly, a major sadistic appliance for all these characters is a relatively grown-up prop, the telephone.) If Roy Rogers had run into any of these creeps he probably would have had a nervous breakdown: by the time they got through with him Dale Evans would have been raped or maimed, Gabby Hayes would have been blown away, and Trigger would have had his ass in a sling.

I suppose some people would argue that Roy Rogers roamed the range in a simpler world, but I’d be inclined to dispute it. All that’s changed, really, is that the childish view of demonology that has always suited us in times of war — yielding our comic-book images of Hitler, Manuel Noriega, and Saddam Hussein, images that worked wonders in getting lots of other people killed (if not the baddies themselves) — now has respectability whether we’re engaged in war or not. Just as a Roy Rogers western could sometimes get young audiences to applaud and stamp their feet, Speed inspired the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane, by his own admission, to stifle a sob (“just the inevitable aftershock of excitement,” he explains).

I can’t imagine Blown Away inspiring many sobs, stifled or otherwise. Certainly not for excitement’s sake: the few first-rate explosions include one big boom that causes a Boston police van to overturn and crush a Boston police car, and then a sequence close to the end; unfortunately, a substandard suspense sequence tacked on after this climax dissipates our exhilaration from the bomb blasts. Early on there are a few suspenseful moments, though the script and Stephen Hopkins’s direction are usually so hyperbolic, so full of high-powered nudging, that we may grow to resent it; and unlike in Speed — which has an equally idiotic plot — there are long stretches between these moments.

When it comes to the villain, Tommy Lee Jones’s mad Irish bomber is so poorly motivated and deliriously mythologized — we’re never offered any clues about how he supports himself or manages to track all the other characters –t hat one feels the filmmakers are merely following the box-office recipe. The few vague motivations screenwriters Joe Batteer, John Rice, and M. Jay Roach do sketch in — involving the Irish pasts of both Jones and Jeff Bridges, the hero — needlessly clutter up the story line. The more unexplained villainy of, say, Malkovich in In the Line of Fire or Hopper in Speed is clearly more in keeping with contemporary tastes. When Blown Away introduces obscure black-and-white flashbacks about the hero, for instance, it’s clearly a rear-guard maneuver; the first time the flashbacks occur, they merely interfere with a defusing-the-bomb-in-the-nick-of-time suspense sequence, and after that they hardly add up to a convincing or comprehensive back story.

Despite the talents of the five lead actors — Jeff Bridges, Tommy Lee Jones, Lloyd Bridges, Forest Whitaker, and Suzy Amis — the movie allows the first four to do only actorly shtick, not play characters in the usual sense at all, and the cliched lines and emotional responses assigned to Amis permit her at best to add a few bumps to the material. The fact remains that, given the popular and critical responses to movies like In the Line of Fire and Speed, a steady string of mindless cliches is considered desirable, because reflection of any kind might slow the action down.

It’s this precondition that makes all the material intended to explain the behavior of the characters feel undigested, shoehorned in. The opening sequence, for instance, which shows Jones blasting his way out of a prison cell in northern Ireland, features a patch of subtitled Gaelic, an ostentatious Irish wedding, and, in the ensuing action, a lot of opportunity for Bridges and Jones to show off their Irish accents — which often makes the dialogue hard to follow.

What the audience wants here is not explanations but a series of kinetic jolts. When Amis and her daughter unknowingly move around a kitchen that may have been triggered to explode by Jones, opening a refrigerator door, clicking on a light switch, plugging in a phone, and turning on the burners on a stove all become momentous events because of the possible high-tech consequences; the audience couldn’t care less about why Jones might have done it. Similarly, after Bridges shuttles his wife and daughter off to the Cape and Jones miraculously turns up at their refuge incognito, the point is not how he found his way there but whether or not he’ll stick his knife into the little girl. (If you don’t want to know, skip the remainder of this paragraph. But chances are you’ve correctly guessed in advance that he won’t; in any thriller as formula-driven as this one, it’s pretty clear that the sweet old codger with the comic quirks — Lloyd Bridges, the Gabby Hayes of Blown Away — is the only member of the hero’s immediate familial circle who’s eligible for decimation.)

I’m not trying to argue that demonology is always a bad thing in suspenseful movies. Consider what writer-director Charles Laughton and actor-villain Robert Mitchum did with the concept in The Night of the Hunter (1955) — an eclectic masterpiece that ironically flopped at the box office and terminated Laughton’s career as a filmmaker, perhaps because the stylistic boldness and ideological implications of this villain, a Bible-thumping serial killer with a switchblade, were more than a 50s audience was ready for. What seems less refutable is that the evolution in villainy from Roy Rogers westerns to current action blockbusters is not entirely a step toward higher sophistication, but in some ways a step down; the special effects are much better but the human impulses are a lot cruder.

Postscript (in the form of a letter, 7/22/94):

In my review of Blown Away last week, an editing error made it sound as if an Irish wedding takes place as Tommy Lee Jones is blasting his way out of a prison cell at the beginning of the movie, and as if Jeff Bridges appears in the opening sequence. In fact the wedding and Bridges’s first appearance take place later in the movie.

Jonathan Rosenbaum