This review appeared in the Chicago Reader on February 5, 1993. —J.R.

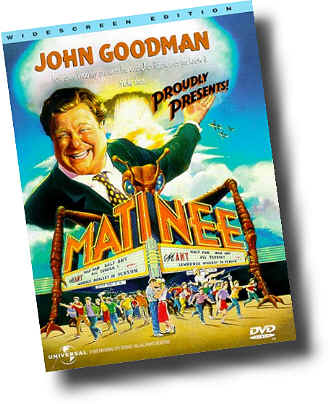

MATINEE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Joe Dante

Written by Charlie Haas and Jerico

With John Goodman, Cathy Moriarty, Simon Fenton, Omri Katz, Lisa Jakub, Kellie Martin, Jesse Lee, Lucinda Jenney, James Villemaire, and Robert Picardo.

I suggested a few new promotional gimmicks for the play — a closed black coffin outside the theater and Oriental incense to get the audiences in the mood. The stage manager agreed to try another of my ideas — Count Dracula would vanish on stage in a cloud of smoke, then suddenly reappear in the audience. Snarling at the frightened spectators, he would again vanish and appear back on stage. I began to learn firsthand the value of good publicity and showmanship.

Adolf Hitler was unwittingly to teach me the lesson again nine years later. Hitler was indirectly responsible for opening the doors of Hollywood for me. — William Castle, Step Right Up! I’m Gonna Scare the Pants Off America: Memoirs of a B-Movie Mogul

It’s not the Russians — it’s Rumble-Rama. — Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) in Matinee

As luck would have it, I saw Joe Dante’s ferocious and lighthearted new comedy, Matinee — about John F. Kennedy “standing up to” Nikita Khrushchev while the world held its breath — barely an hour after reading in the paper that the world was holding its breath to see if Bill Clinton, in his first days of office, would “stand up to” Saddam Hussein. Despite the intriguing coincidence I doubt that many of my colleagues will jump to the conclusion that Dante has made a movie with anything at all to say about the way we live and think today. (Remember Deep Cover: just another cop thriller, most said or implied, with no relevance to the Bush administration or to our own lives.) After all, Matinee is set during the Cuban missile crisis — it’s about war fever in 1962. Moreover it’s extremely funny, charming, and entertaining, the way movies are supposed to be but seldom are nowadays. To assume that anything that’s so much fun is also telling us something about how we behave both as film spectators and as warmongers, not only three decades ago but right this minute, is to grant a seriousness to our amusement obviously greater than the culture can bear.

But consider how the dark side of spectatorship and the ideology of popular entertainment — the way movies turn us into gremlins — has been central to all of Dante’s best work, even at its most nostalgic, film-buffy, and apparently frivolous. His 1984 Gremlins gave us adorable little beasties that turned into monsters very much like us — especially in their bratty behavior when they watched a beloved Disney cartoon feature in a movie theater. The Dante segment in Twilight Zone–The Movie amplified this idea by establishing a vindictive, Sadean universe created in the mind of a little boy who’s watched too many cartoons, while the nightmarish finale of Explorers gave us the world of American TV strained through the consciousness, physicality, and technology of extraterrestrials.

Dante’s 1989 The ‘Burbs, which conjured up an old-fashioned horror movie, brought the critique of spectatorship even closer to home by ridiculing the xenophobia of a suburban man (Tom Hanks) spying on his next-door neighbors and satirizing the uninvolved voyeurism of teenagers watching and enjoying this snoop as if they were plunked down in front of their TVs. The somewhat earlier Innerspace brought new meanings to notions of voyeurism and coexistence by following what happened when a miniaturized Navy pilot (Dennis Quaid) got injected into the body of a hypochondriac (Martin Short), creating intercut parallel narratives that were like movies within movies. Even Gremlins 2: The New Batch, though it’s the least ambitious conceptually of Dante’s recent efforts, brought back the beasties as grubby little versions of ourselves at our most consumerist.

A horror-movie schlockmeister is the central character in Matinee — a jovial showman named Lawrence Woolsey (John Goodman) who’s clearly modeled on William Castle, master of the horror-exploitation gimmick (and underrated director of some earlier noir-ish B-films like When Strangers Marry and The Whistler). Woolsey’s relation to the Cuban missile crisis is clarified when he takes on the role of surrogate father to 15-year-old Gene Loomis (Simon Fenton), who has recently moved to Key West with his family. Gene’s father, who’s in the Navy, has been “sent out” to parts unknown on the day the story opens, shortly before a special bulletin interrupts Art Linkletter’s TV show People Are Funny to bring on President Kennedy demanding the withdrawal of offensive missile sites recently spotted in Cuba.

In fact, Gene’s father never puts in a single appearance in Matinee — unless one counts some brief glimpses of him in a home movie his wife (Lucinda Jenney) tearfully watches — so one might say that, mythically and emotionally, Kennedy in his sole TV appearance is the father’s replacement. But Woolsey — “America’s number-one frightmaster,” as he calls himself — is present in the opening scene, in a trailer for his latest horror production, which Gene watches; shortly thereafter we learn that Woolsey will be appearing in person at the theater, on Saturday, to present a special matinee preview of his film. In fact, as soon as Woolsey appears in the flesh, not long after Kennedy’s speech, he becomes the movie’s most important patriarch, supplanting Kennedy, Adlai Stevenson (who appears briefly at UN hearings on TV), and Gene’s missing father — a more ideal version of all of them.

Soon after Woolsey arrives for his show — which involves an elaborate setup with buzzers under the seats and apparitions in the aisles, neatly summarizing some of Castle’s most celebrated gimmicks — the panicky theater manager (Robert Picardo) objects that the country is “on red alert.” “Exactly,” says Woolsey. “What better time to open a horror movie?” And as we discover, Woolsey’s arsenal of scare tactics is every bit as effective as Kennedy’s. Just as the fear of nuclear holocaust creates a hoarding panic among shoppers at the supermarket, Woolsey’s own show reduces his audience to hysterical popcorn fights even before the movie starts. Similarly, the two scaremasters prove equally successful at inspiring hasty retreats; shortly after Woolsey averts disaster by conjuring up a fake nuclear holocaust to drive the audience out of the theater, it’s reported in the news that the implied threat of nuclear holocaust has attained comparable results with the Soviets: Khrushchev has promised that the missiles in Cuba will be dismantled.

I don’t mean to imply, however, that Matinee is didactic, devoted to simple one-to-one correspondences, preachy meanings, or pretentious undertones. And for those who might object to my claims about the movie’s contemporary relevance — those who consider the Cuban missile crisis “serious” and the war drums being beaten in Saddam Hussein’s ears not, as well as those who think the reverse — my point is merely that the movie traces the kind of unthinking giddiness and/or blood lust that fear produces in an anxious audience. Whether the sources of anxiety are Castle’s Homicidal and Nikita Khrushchev or The Silence of the Lambs and Saddam Hussein, our taste for horror-movie monsters who provoke bloody reprisals has persisted for most of this century — a taste that becomes especially pronounced whenever our trigger fingers get itchy. (Less persistent are our memory and awareness of the human cost of scratching those itches — most recently, even currently, our slaughter of innocent ethnics unlucky enough to live under the thumb of Saddam Hussein and therefore ideally suited as cannon fodder, for our grand humanitarian schemes as well as his.)

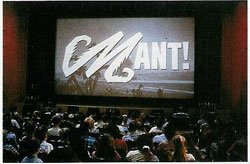

The glory of Dante’s comedy in this movie and others — as aided and abetted by his usual production team, producer Michael Finnell, cinematographer John Hora, and screenwriter Charlie Haas — is that it suggests poetic parallels without insisting on them. Just as a backstage bomb shelter — a chamber in which Gene and his radical girlfriend (Lisa Jakub) become briefly and romantically trapped — bears an interesting resemblance to a bank vault, the kind of war fever Matinee examines has more than one point of contact with the emotions elicited by bad low-budget horror films: Matinee satirically cross-references early-60s fears of nuclear holocaust with Woolsey’s ludicrous new picture, Mant, about a man transformed by radiation into a giant ant. (“Young lady,” one character intones, “human-insect mutation is far from an exact science.”)

Inhabiting a corner of junk heaven in all his pictures, Dante clearly regards each project as a fresh opportunity to show off his appreciation of pop culture. And his pleasure in using familiar bit players such as Jesse White (here the owner of a theater chain) and Dick Miller and John Sayles (members of Citizens for Decent Entertainment) is palpable. As a TV illiterate, I can’t comment on the way TV shows past and present have affected casting decisions and the dialogue, though when it comes to movies Dante has obviously taken full advantage of his resources. It doesn’t seem accidental, for instance, that Cathy Moriarty — Woolsey’s somewhat resigned girlfriend, leading lady, and all-around assistant — reminds us through her accent of her debut role in Raging Bull.

We glimpse a profusion of 1962 “one-sheet” movie posters in the lobby of the film’s theater, the Key West Strand — a pantheon including The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Hatari!, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Lonely Are the Brave, and Confessions of an Opium Eater. It seems Dante is ticking off his favorites, even if this means working in many more posters than one could imagine such a theater displaying at once. He’s also created many “excerpts” from movies showing in the theater — including a Mant trailer, Mant itself (both in black and white), and something called The Shookup Shopping Cart, a color feature that suggests both Frank Tashlin and live-action Disney. At the same time that Dante has a field day brutally satirizing our desire to scare ourselves and others, he also re-creates early-60s clichés with a relish and a feeling for detail that come very close to love.