This appeared in the Chicago Reader in their Christmas issue (December 25) in 1992. — J.R.

The presumption behind most ten-best lists is that they include items available to everybody. One can always look at such lists and say, “Too bad I missed such and such. Maybe I’ll catch up with it on video.” But few people seem to be aware that they may never catch up with a film, because it never made it to Chicago at all—either to theaters or to video stores. In a consumer culture like ours we aren’t supposed to think too much about what merchandisers choose to put in front of us; it’s better for business if we assume that new movies just fall from the sky into theaters and video stores—and that those that don’t make it don’t deserve to. However, I see a certain number of movies in other countries every year that don’t make it to town, and sometimes they’re better than the movies that do. Why this happens so often is a matter worth exploring briefly.

In 1938 the U.S. government filed an antitrust action against Paramount Pictures, objecting to the monopolies of movie theaters held by the studios. By the end of 1946 a court judgment enjoined not only Paramount but also Loew’s, RKO, Warner Brothers, and 20th Century-Fox from acquiring additional theaters. By the late 50s and early 60s the more open market for movie exhibition created by these rulings led to more independent theaters, including art houses that specialized in foreign films and, by the early 70s, midnight movies. (Both tended to flourish because films were rented for a flat fee rather than on a percentage basis, granting a lot of creative freedom to individual programmers about what to show.)

In the 80s, however, the Justice Department under the Reagan and Bush administrations refused to enforce antitrust laws (in Washington, I’m told, the antitrust division is jokingly referred to as the “trust division”). As the market began to shrink accordingly, the alternative venues became shadows of their former selves. Meanwhile, the growth of the “infotainment” industry—devoted to granting free publicity in all the media to studio products and little or no attention to anything else—has made the survival of independent movies and theaters even more precarious. Finally, the recent gutting of the NEA—a major source of funding not only for independent filmmaking but also for nontheatrical distribution and exhibition–by Donald Wildmon and other wild men has delivered the coup de grace to practically everything but what the studios decide to shove our way. In practical terms this means that a local resource as vital as the Art Institute’s Film Center now has to operate on a pittance—partially as “punishment” for controversial artworks exhibited by students at the School of the Art Institute a few years back—forcing it to cut back on some of its riskier and costlier programming. It also means that the International Film Circuit, whose invaluable “Cutting Edge” programs have showcased major foreign pictures like The Horse Thief and Life Is a Dream in noncommercial venues all over the U.S., will have no such program in 1993 because it failed to get another NEA grant. Unlike most civilized countries in the world, we regard light entertainment as a necessity but don’t regard art that way, to judge from the attention accorded each sphere on TV. Joe David Bellamy recently wrote in the Nation that Canada’s population is less than ten percent of ours, but the Canadian Council’s annual allocation of funds for literature is more than five times larger than the NEA’s.

Needless to say, with most movie alternatives factored out of our lives by such conditions, the totalitarian rule of the major studios and distributors over our consciousness has become virtually unquestioned, and this naturally has a direct effect on our thinking as well as on our viewing habits. At a panel discussion devoted to Malcolm X a few weeks ago a couple of audience members remarked that even if we criticized the film the very fact that we were discussing Malcolm X at all meant we owed Spike Lee our sincere thanks. It’s a reasonable enough comment on the face of it, yet it’s come back to haunt me again and again. Does this mean that the many serious scholars and political thinkers who’ve been devoting years of their life and work to Malcolm X don’t deserve our thanks because they didn’t wind up on Entertainment Tonight? Does it mean in effect that, like citizens of Stalinist Russia who were expected to vote for the Stalinist candidate even when there weren’t any others to choose from, we’re supposed to be grateful to Warner Brothers for granting us the opportunity to think about Malcolm X? Regardless of whether they botch the job and regardless of how much money they’re making off our interest, it’s somehow generally assumed that they’re a charitable organization with our best interests at heart—perhaps because the media virtually treat them as such.

That’s why it seems to me that most ten-best lists, not to mention the Academy Awards, function as ratifications of a narrow list of choices; they’re meant to mask our lack of freedom in this process. It reminds me of the scam practiced by a Florida-orange-juice stand advertising “all the orange juice you can drink for a dollar”: you’re given just an ounce, then told, “That’s all you can drink for a dollar.” Each of our ten-best lists and Oscars represents merely a chunk of all we can see for seven dollars, and what we can’t see—no matter how good or important—isn’t even in the running.

Below are my favorite movies of 1992 that you can’t see, along with some reasons why you can’t. I saw them all at film festivals in Rotterdam, Locarno, and Toronto—except for the first, which I saw at a recent Orson Welles conference in Rome.

1. Don Quixote. Orson Welles’s ultimate plaything, which he financed himself, was a feature he started in the mid-50s and kept working on intermittently until he died 30 years later. He loved working on the film too much ever to complete it, and considering the rough treatment he got from critics for nearly all the movies he did finish, it’s easy enough to understand why he wasn’t in any rush to release this one. Adapted from the Cervantes novel, it features Quixote (Francisco Reiguera) and Sancho Panza (Akim Tamiroff) in 17th-century garb wandering through 20th-century Spain and Mexico—the implication being that these figures and what they embody are still very much with us. For all its incomplete and rough form, it’s still one of the most beautiful and poetic achievements of Welles’s entire career, even earthier and more richly tragicomic in some respects than his sublime Chimes at Midnight.

About a year ago most of the surviving Quixote footage and related material—comprising about a dozen hours of edited and unedited film, an hour of it with sound—was sold to the Spanish national film archives in Madrid. Provisions were made for a commercial feature to be prepared from the material for Spain’s Expo 92 by hack director Jesus Franco, who had worked for Welles as an assistant on Chimes at Midnight. Having no script to work from and only a few months to “complete” a work that Welles spent nearly 40 years on, Franco wound up including material from Welles’s very different In the Land of Don Quixote (a rather pedestrian nine-part home movie about Spain made for Italian television in the 60s) and dubbing in Spanish dialogue from the novel, most of it apparently selected at random. The resulting disgrace premiered in Spain last spring and was poorly received at Cannes in May. An English version is said to be in preparation, though whether it will eventually wend its way to Chicago or respect Welles’s original intentions is far from clear.

I saw the Spanish version on video, unsubtitled, in Paris last August, but at two separate Welles conferences four years apart—one in New York in 1988, the other in Rome last October—I was able to see about an hour of the extraordinary original edited footage, about half of which has sound. (The voices of both Quixote and Panza are dubbed by Welles himself, who also figures at times as narrator.) To complicate matters further, part of what I saw in Rome was edited footage that doesn’t belong to the Spanish film archives and is therefore currently part of a lawsuit. Whether this footage will ever become available over here is uncertain, though the Italian media obviously have a different sense of priority about such matters—portions of it have already been screened on national TV.

Like Humpty-Dumpty, Welles’s Quixote survives as shards and fragments; if they were all put together they’d probably add up not to a single film but to several, each one planned by Welles over a separate period. The earliest surviving portion of Quixote that I know about, which I saw in Rome, features Welles himself telling the story to a pigtailed 12-year-old Patty McCormack in a hotel garden and later in a horse-drawn carriage, and still later in a silent sequence shows the girl encountering both Sancho Panza and Quixote in a movie audience. (While watching a movie she teaches Panza how to unwrap and suck a lollipop, then they both observe the doleful knight rise from his seat and march down to the movie screen with his sword to save a damsel in distress, slowly and methodically slashing the screen to shreds while kids in the balcony lustily cheer him on; the scene begins as low comedy and ends in almost unbearable pathos.)

Rough or not, this 50s material is probably the best cinema of any kind I’ve seen all year, but don’t count on any of it ever getting onto Entertainment Tonight or PBS, much less into your local multiplex. As suggested above, they order things differently over here, and Welles’s Quixote–which never could have been a “commercial” movie, despite its awesome beauty and power—has no retail value whatsoever in its patchy unfinished state.

2. A Brighter Summer Day. Sometimes the reason a great movie doesn’t make it to town is purely circumstantial. This Taiwanese masterpiece by Edward Yang about the events leading up to the murder of a teenager by her boyfriend in 1960, inspired by an actual event, exists in two versions, one of them over three hours long, the other nearly four hours. I saw the three-hour version twice last year—once in Toronto and a second time in Taipei—and the four-hour version once in Taipei. (Both versions are certainly impressive, but I prefer the longer version, finding it much easier to watch because it’s much more lucid and purposeful as story telling.) The film’s title refers to the lyrics in an Elvis Presley song, and much of the plot concerns the machinations of two rival high school gangs; the film’s greatness is in, among other things, its mise en scène, the remarkable ensemble acting of its mainly nonprofessional cast, and the intricate, novelistic charting of the histories of a few key objects—a radio, a flashlight, a tape recorder, and a Japanese sword—through a dense and cumulative story line.

Barbara Scharres, director of the Film Center, was all set to show the four-hour version as part of a Yang retrospective this year, but was stopped dead in her tracks by Yang himself, whose objections stemmed from a quarrel with his distributor rather than anything involving Chicago or the Film Center. This was a source of some frustration for me as well as for Scharres, because I was primed to write a four-star review explaining why I consider this in some ways the strongest Taiwanese feature I’ve ever seen—even more powerful in certain respects than the great work of Hou Hsiao-hsien (A Time to Live and a Time to Die, City of Sadness, etc.) Yang’s masterpiece did wind up getting screened—in the four-hour version, if I’m not mistaken—in New York and Los Angeles, but apparently received no significant reviews before or after. (In New York major works are ignored and lost in the shuffle on a regular basis, unobserved and uncovered by journalists because of the sheer volume of what passes through the city; the most recent casualty I’m aware of is the original uncut, 70-millimeter version of Jacques Tati’s Playtime, which screened last month at New York’s Museum of Modern Art.)

The bitter truth is that no Taiwanese feature has ever received any art-house distribution in the U.S., and only one or two (not including A Brighter Summer Day, alas) have ever shown at the New York film festival. Given our present isolationist climate, this situation is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. How good any particular Taiwanese movie is or how much it might have to say to us is, strictly speaking, irrelevant. To all appearances, distributors and most programmers have decided in advance, probably on the basis of past experience, that “we” couldn’t care less about any feature from Taiwan. (“We,” I should add, omits the Chinese American viewers who can see Taiwanese features, usually subtitled in English, in Chinese theaters or rent them from Chinese video stores. Because English titles that would identify these films are usually absent, the only people likely to seek them out are those who read Mandarin.) The only way A Brighter Summer Day could conceivably turn up here outside of Chinatown is through the Chicago International Film Festival, the Film Center, or Facets Multimedia; having failed to materialize for whatever reasons at any of these venues, it hasn’t much chance of being shown here. Let’s try to be optimistic: maybe it’ll come out here on video before, say, the year 2001. But I wouldn’t take bets on it.

3. Les amants du Pont-Neuf. Because of various technical difficulties involving set construction that stretched over years, Leos Carax’s third and best feature, which I saw unsubtitled in Rotterdam, is one of the most expensive and lavish features in the history of French cinema. A poetic extravaganza centered on a love story between a Parisian street punk/fire-eater named Alex (Denis Lavant, who starred in Carax’s two previous features, playing a character with the same name) and a slumming street artist (Juliette Binoche), the film is as patchy in its own way as Carax’s Boy Meets Girl and Bad Blood, but its highs are the most ecstatic and beautiful he has come up with. Most if not all of these highs derive from spin-offs of the romantic notion of Paris as a personal toy that has sustained the French cinema all the way from René Clair’s silent Paris qui dort (The Crazy Ray) to Tati’s Playtime to the first episode in The Little Theater of Jean Renoir.

Why can’t you see this wonderful movie, which showed at the last New York film festival? The answer is quite simple: because Vincent Canby, film critic of the New York Times, didn’t like it, which is enough in this country to kill a foreign film’s chances of getting a distributor. (This also explains why Michelangelo Antonioni’s last feature and Maurizio Nichetti’s first, among countless others, have never opened in U.S. theaters.) This unexamined state of affairs is commonly regarded within the film world as a simple fact of life, equally operative when Canby’s long-term predecessor Bosley Crowther had the job; chances are it will continue to hold force as long as distributors and exhibitors are so cowardly and unadventurous that they’ll let the Times critic make all their major decisions for them. Equally unexamined is the notion that New York is intellectually the most sophisticated American city when it comes to movies—yet how could that possibly be when many thousands of lunkheads there, apart from the distributors, let one measly cultural commissar do all their thinking for them?

4. Mama. In mainland China “uncommercial” works like this independent feature by Zhang Yuan, which I saw in Rotterdam last January, are simply banned, though I’m told a healthy video black market puts them in the hands of several filmmakers. The subject of Mama is children with learning difficulties, and the film alternates between an emotionally subdued black-and-white fiction about a mother who goes to a clinic with her son after belatedly acknowledging that there’s something wrong with him and emotionally charged documentary interviews in color video with the real-life counterparts of such parents and children.

What’s exciting about this unconventional method is that it shows there’s more than one way of responding to every aspect of the film’s subject, and the audience is respected rather than manipulated in relation to these choices. Significantly, the film’s screenwriter, Qing Yan, the mother of a child with a learning disability, appears in both sections of the film, as both the fictional mother and herself, and it’s up to us to sort out our responses to her two “characters.” Despite the Chinese ban on the picture, Mama has attracted enough interest from its Rotterdam screening to have some chance of reaching the U.S., either in noncommercial venues or on video. But don’t hold your breath.

5. Antigone. If Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet’s latest feature is to reach these shores, it will have to be subtitled. Efforts are being made to raise enough money to carry out this work on Antigone and on Straub and Huillet’s short Black Sin. (In the case of their hour-long Cézanne, which the filmmakers are unwilling to have subtitled, some other form of translation will have to be undertaken.) Considering the difficulty of their films, this is an uphill battle to say the least; but if such dedicated academic supporters of their work as Barton Byg on the east coast and Thom Andersen on the west coast can sustain their passionate project, we’ll eventually get to see these beautiful and uncompromising films in Chicago. (Perhaps the Goethe-Institut, which was responsible for bringing us the exciting and invaluable Haroun Farocki programs early this year, can be enlisted.)

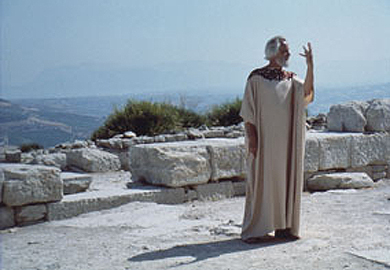

Practically every Straub-Huillet film departs from a single text; in Antigone it’s Brecht’s adaptation of Hölderlin translation of Sophocles’ tragedy—a triple challenge with historical roots in four separate centuries. It follows on the heels of Straub and Huillet’s two other “settings” of Hölderlin with togas and sandals, The Death of Empedocles and Black Sin, but it’s punctuated by rapid camera movements and even more spectacular vistas. This utopian dialectical-materialist mix of raw nature and acted text, filmed in the ancient ruins of a Sicilian theater, was screened outdoors in Locarno’s town square for many thousands of people at once—the boldest move of new festival director Marco Müller, matching Straub and Huillet’s utopian purity and intransigence with his own. Despite the expected walkouts and jeers, a surprising number of spectators stayed, watched, and listened.

6. Family Portrait. Another film from mainland China, this is about as commercial as they come in a Chinese context—a contemporary soap opera with lots of nicely handled comedy that was put together as a package pairing a popular male lead and a child TV star as his son. A photojournalist living in Beijing with his wife and toddler suddenly discovers that his previous marriage to a peasant during the Maoist period yielded a son, who is on the verge of adolescence and is coming to join him now that the mother has died; a good many comic and not-so-comic complications ensue when the photographer has to break this news to his present wife, who has just become pregnant again and, according to Chinese law, must have an abortion.

What I like most about Family Portrait—apart from the deft handling of actors by director Li Shaohong, one of the few “Fifth Generation” women directors—is how much it reveals about everyday life in Beijing today. It would be nice to assume that a lot of other Americans are interested in discovering how some of the billion people in the world’s largest nation live, but it seems that American distributors—perhaps anticipating Vincent Canby’s taste—have decided we aren’t; apparently the only China we can care about is contained in the consumerist period-fantasy elements of Raise the Red Lantern.

I saw Family Portrait in Locarno, where the director had come on her very first trip abroad. (Her previous feature, a Chinese adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold, was also shown.) It seemed strange to me that her whole view of the West would be based on her ten days in a Swiss-Italian lakeside resort, but it’s probably even crazier that our view of Chinese life today from films should be based almost exclusively on period pictures. For the record, Li optimistically told me she thinks this situation will change.

7. The Day of Despair. Another film shown in Locarno, this world premiere was a curious yet compelling twilight work by the greatest of all Portuguese filmmakers, Manoel de Oliveira, none of whose films has ever been distributed in the States (though nearly all of them have shown in Chicago at one point or another—mainly at the Film Center and more recently at the Chicago International Film Festival). Now in his mid-80s, de Oliveira is the only working director I can think of who began his career during the silent era, but the modernism of The Day of Despair and most of his other work since the 70s shows that he is anything but old hat. Based on the correspondence of the famous and prolific Portuguese writer Camilo Castelo Branco (1825-1890) during the last years of his life, when he was going blind, this is a mellow chamber work about the inner struggle that eventually led to his suicide. Not a great work on the level of either Doomed Love (de Oliveira’s four-hour 1978 adaptation of Castelo Branco’s most famous novel) or Francisca (another de Oliveira feature about this writer’s life, made in 1981), this is still a stirring and serious film, considerably better than his Divine Comedy (1991), a painfully empty exercise shown at the Chicago festival this year. Let’s hope they remember The Day of Despair when the next festival rolls around.

8. BoulevardS du crépuscule. I can’t tell you why the S in “boulevards” is capitalized, but I can say that this hour-long essay by Paris-based Argentinean writer and filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky, which I saw in French in Locarno, is probably the best Cozarinsky film I’ve seen since his 1981 masterpiece One Man’s War. A reflective and personal piece of investigative reporting, it follows Cozarinsky’s recent return visit to Buenos Aires, where he searches out the sites of the lost movie theaters of his youth and researches the final days of two French actors who lived in that city—Falconetti, the unforgettable star of Carl Dreyer’s silent The Passion of Joan of Arc, and the supporting film actor and wartime collaborationist Robert Le Vigan. It’s quirky and fascinating, and I would love to see it again, preferably subtitled in English.

9. The Long Day Closes. Terence Davies’s exquisitely beautiful British feature, an autobiographical sequel to his magnificent Distant Voices, Still Lives set during the mid-1950s, was the very first film I saw at the Toronto film festival last fall, and I recall emerging from an early-morning screening with a slight sense of disappointment that it wasn’t more of a departure from—or development of—his previous masterpiece. But then I recalled that Distant Voices, Still Lives, as powerful as it is, didn’t yield everything the first time around, and I looked forward to seeing the film a second time when it came to Chicago. After all, every shot in a Davies film is a genuine artistic event, and art, unlike entertainment, occasionally requires something other than instant consumption and digestion.

But now it appears that, having failed to get into the New York film festival or to find a U.S. distributor, the film is not likely to reach this country anytime soon, unless the Film Center or Facets has the desire and wherewithal to book it. To my way of thinking, Davies is one of the key English filmmakers, living or dead, and anything he does is bound to be of major interest. I’d much rather see his new movie a second time than just about any Hollywood film released this year.

Like Distant Voices, Still Lives, The Long Day Closes is in no way esoteric or intellectual; the sheer emotional weight and the remarkable sense of economy and condensation in the images and sound are immediately communicated, and the only thing challenging about the film is its sheer intensity. But the fact that Davies doesn’t make conventional story films places him at an enormous disadvantage in relation to conventional art-house directors, whose films can be more easily synopsized, packaged, and promoted by distributors and reviewers. And, sad to say, most distributors and reviewers, because they’re concerned with matters of labels and descriptions, have little in common with the ordinary spectator. It irritates them that movies such as Davies’s exist and thereby confound the safe genre categories that legitimize everything from Unforgiven to Universal Soldier to The Distinguished Gentleman, and we all have to live with the consequences of that irritation.

10. Careful. The two previous features of Winnipeg weirdo Guy Maddin, Tales From the Gimli Hospital (1988) and Archangel (1990), have both made it to Chicago, and I suspect that this one, his first in color, will eventually wend its way to us as well, though it’s still hard to know when or how. Set in an alpine village where the people live so fearfully under the threat of avalanches that they speak in whispers, the film has much of the deadpan early-talkie texture of Maddin’s previous work, and the specifically Canadian aspects of his theme and story—involving incestuous longings and other perverse secrets along with an abnormal sense of caution—are even more apparent. Shot exclusively on studio sets that bear Maddin’s distinctive stamp, with an appropriately oddball cast that includes Jackie Burroughs and Australian director Paul Cox, this is a brand of serious nocturnal camp that would undoubtedly play well at midnight, and if we’re lucky it may get to Chicago in that kind of programming slot in 1993. For the time being it’s simply too strange and wonderful—too much like art, in spite of its considerable value as entertainment—to be treated with the respect and urgency automatically accorded Home Alone 2 or Toys.