This appeared in the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1992), and is reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

RHAPSODY IN AUGUST

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Akira Kurosawa

With Sachiko Murase, Hisashi Igawa, Mie Suzuki, Tomoko Ohtakara, Mitsunori Isaki, Hidetaka Yoshioka, and Richard Gere.

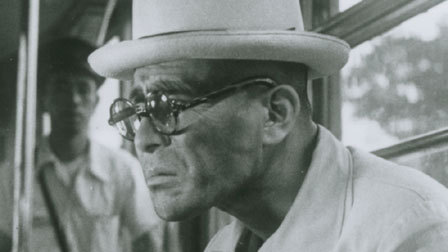

Next month, Akira Kurosawa will be celebrating his 82nd birthday. Having long outlived the two other supreme masters of the Japanese cinema — Kenji Mizoguchi, who died in 1956, and Yasujiro Ozu, who died in 1963 — he bears the handicap of living on in an era that clearly seems remote and alien to him, despite the fact that his work has enjoyed much more currency in the 80s and early 90s than that of any of his near-contemporaries.

I’ve always been somewhat slow to appreciate the mastery of Kurosawa in relation to the works of Mizoguchi and Ozu, perhaps in part because I started off on the wrong footing. The first Kurosawa film I ever saw was Rashomon (1950), the single movie that was most responsible for introducing the western world to the Japanese cinema, and, as it happens, I saw it as a teenager only after reading the two short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa that it was based on. The most important of these two stories, “In a Grove,” offers seven conflicting testimonies about a single incident involving rape and murder. Kurosawa’s film incorporates four of these testimonies, but frames them in a manner that radically undermines their original implications. Akutagawa’s story offers no conclusion, and because none of the testimonies is privileged, the radical implication of the story–irrational by any conventional standards — that all of the testimonies are truthful. Kurosawa’s much softer and sentimental conclusion, which is made clear in his framing story, is that everybody lies, a “message” that clearly rationalizes the philosophical conundrum of the original.

My irritation with this change has tended to bias me against the sentimentality of much of Kurosawa’s work ever since. It might be argued that, apart from Rashomon and The Seven Samurai, most of this sentimentality figures in his contemporary films while his period films, which are usually much more action-oriented, tend to be purer in intent. But if even Kurosawa’s greatest contemporary works, such as Ikiru and High and Low, have their saccharine elements, it might also be argued that his greatest period film, Throne of Blood, manages to avoid sentimentality only by running the risk of ruling out humanist emotion altogether.

Given the awesome size of Kurosawa’s achievement over half a century, I fully admit that this bias is more than a little churlish. Indeed, now that I find that his latest feature, Rhapsody in August, is being castigated across the globe for its sentimentality and irrelevance, it seems like a good time to come to Kurosawa’s defense, especially since I find this film at the very least more affecting and accomplished than any of his movies since Kagemusha (1980).

As Kurosawa’s last film, Dreams, made clear, he’s more than a little horrified by the modern world — sentiment I happen to share — and places all of his trust in the elderly and in children while castigating the adults in between, a sentiment I can readily understand but feel somewhat more skeptical about, if only because it smacks of expedient simplification. It’s a sentiment that lies at the heart of Rhapsody in August, and the movie would be inconceivable without it, but I don’t believe, on the other hand, that the value of the film — which is tied in part to its transgressiveness — can be reduced to this premise. We’ve recently finished commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Kurosawa’s film enacts a commemoration of the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki four years in advance of the fiftieth anniversary of that event, and it seems to me that the discomfort that is widely felt with this movie has much more to do with this fact than it does with its partiality towards the old and the young.

Before getting to the particulars of Rhapsody in August, it seems worth pointing out that this isn’t Kurosawa’s first film about the atomic bomb. I haven’t seen the previous one, I Live in Fear (also known as Record of a Living Being), which was made in 1955 — ten years after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki — and one reason why I haven’t is that it’s probably the biggest commercial and critical flop in Kurosawa’s career to date (although some notable critics, including Georges Sadoul and Noël Burch, have written strongly on its behalf). The plot features Toshiro Mifune as a 70-year-old who is so shaken by information about radioactive fallout (after the recent Bikini test explosions) and the possibility of further nuclear holocausts that he insists on forcing his entire large family to emigrate to Brazil. Declared incompetent by members of his family, who bring him to court, he winds up confined to a mental hospital.

It seems significant that the cool international reception accorded to I Live in Fear has been virtually duplicated in the responses to Rhapsody in August. (I can testify to the dismissal of the recent film in Asia on the basis of what I heard from several critics in Taiwan late last year; faces were made every time I brought the matter up.) Clearly less satirical or ironic in intent, Rhapsody in August, based on Kiyoko Murata’s novel Nabe-No-Naka, centers on Kane (Sachiko Murase), an elderly woman who survived the Nagasaki explosion and still lives in the same area in the nearby countryside. While her son Tadao (Hisashi Igawa) and his wife are off in Hawaii for most of the summer visiting his uncle, now dying, who has become a very successful pineapple grower, her four grandchildren are staying with her in the country, and trying to persuade her to visit her brother herself, bringing them along. (“Going from Nagasaki to Hawaii is the same as going from Nagasaki to Tokyo,” one of them argues.) She eventually agrees, and writes to the Hawaiian relatives that she will come, but only after she attends a memorial service to her husband, who was killed by the atom bomb. After visiting the schoolyard in Nagasakiwhere their grandfather died, now turned into a small memorial, the grandchildren begin to learn more about the past, beginning with the names of Kane’s many other siblings, and visit places in the nearby countryside associated with them (as well as with the nuclear explosion), such as a cedar grove in the mountains and a waterfall basin.

Then the children’s parents arrive. Tadeo speaks about the possibility of jobs offered there by Clark (Richard Gere), the Japanese-American son of Kane’s dying brother, and admits that he never told the Hawaiian relatives that his uncle was killed by the bomb. Kane is offended by his and his wife’s mercenary interests while the grandchildren are equally offended by their cynical decision to conceal how Kane’s husband died.

Kane has already spilled the beans about her husband in her letter to Hawaii, and Clark arrives to visit them soon after the return of Tadeo and his wife, deeply moved by the news and eager to learn more. After attending the memorial ceremony commemorating the death of his uncle and other victims of the Nagasaki holocaust, he receives word that his own father has died, and takes the next plane back to Hawaii. The family plans to follow him, but Kane, grief-stricken by her failure to see her brother again before he died, begins to re-experience the past directly. (As one of the grandchildren puts it, “The clock in her head is running backwards.”) Waking during a thunderstorm, she rushes out of the house into the rain, believing that the bomb is falling, and in protracted slow-motion, the members of her family chase after her, never catching up.

At no point in Rhapsody in August is any historical or political explanation for the Nagasaki explosion offered, much less refuted, apart from “war”. While it’s been argued against the film that this omission coincides with the gaping deletions on this subject found in school textbooks in Japan — deletions that I suspect are worse but still not radically different from those found in U.S. textbooks — I think it can also be argued that historical finger-pointing about the bomb is irrelevant to Kurosawa’s purposes. When the grandchildren visit monuments to the Nagasaki holocaust contributed by countries from all over the world, and we’re presented with a montage of these monuments, each one identified by country to strains of Vivaldi, one of the kids remarks, “I don’t see one from America,” and is simply told, “America dropped the bomb.” This isn’t finger-pointing but simple factual information, and it might be added that, if anything, the mythical treatment accorded to Richard Gere in the film when he turns up speaking Japanese — presented as if he were a visiting prince (in spite of the fact that Gere’s humility in the part makes it for me his only bearable performance) — makes it perfectly clear that American-bashing isn’t even remotely part of Kurosawa’s agenda. It would be more accurate to say that his emotional loyalties are exclusively with the perceptions of Kane and her grandchildren, and with Gere’s Clark insofar as he shares them — perceptions that war itself is a crime committed by rulers and sustained by conformist adults (represented here by the parents) against “the people”, without reference to nationality or politics.

What might be regarded as the narrowness or naivety of Kurosawa’s vision of the bomb’s meaning is actually a passionate form of commitment to the people who experienced it directly and those whose still-uncorrupted innocence allows them to discover the truth of that experience in strictly personal terms. This is far from being a fashionable way of approaching the subject, but it is equally far from espousing the nationalistic and other ideological alibis that might serve to “explain” the bomb while ignoring or dismissing those personal experiences.

In fact, the major stylistic influence in evidence in Rhapsody in August is late John Ford, Donovan’s Reef in particular. Kurosawa has often acknowledged Ford as a major influence, and Seven Samurai, for instance, offers a clear example of this — although ironically, the same film led to The Magnificent Seven and its sequels. (Crosscultural influences have played significant roles elsewhere in Kurosawa’s career. Some have claimed that Yojimbo, which helped to spawn the spaghetti western, derives in part from Dashiell Hammett’s Red Harvest.)

The relationship of Rhapsody in August to Donovan’s Reef can be seen and felt in many particulars: in the rapport and complicity between the very old and the very young, in the mythical treatment of Hawaii as a form of utopia (particularly as a site of crosscultural synthesis and intermarriage), in one of the grandchildren’s comments about Clark (“He’s as tall as John Wayne!”), in the pastoral celebrations of nature, and even in the eventual repair of an oldtime organ to accompany a festive communal singalong (in Donovan’s Reef, it’s a slot machine). It could be claimed, for that matter, that the regal treatment accorded to Clark/Gere in the movie isn’t merely a matter of kowtowing to a Hollywood star, but also a function of seeing this character as an emissary from Utopia because he’s a Japanese-American raised in Hawaii.

The film’s poetry isn’t merely a matter of this overall pastoral ambiance, some of which could also be found in Dreams, but also a matter of illustration and inflection, visible in both the framing and the editing. We learn that one of Kane’s long-dead brothers, who lost all his hair when the bomb fell, spent most of his time afterwards drawing eyes; one of the grandchildren draws a similar eye on a blackboard, and Kurosawa briefly and effectively cuts back to this eye at later stages. When Kane later recalls the flash of the explosion itself as a giant eye, the film promptly illustrates this surreal vision — a gigantic eye opening between the sky and the mountains. And when two of the grandchildren return home one day from the cedar grove, they learn that an old lady, another survivor of the explosion, is visiting Kane without either of the old women saying a word; beautifully violating a standard rule of editing, the film cuts directly from a shot of the two of them framed through an open window to a closer shot from the same angle inside the room, with each woman situated at opposite ends of the frame.

Some narrative details range are homey and touching: the grandchildren complain to Kane about her cooking, making the food too soft because of her own dentures; later, after an older sister takes over this chore, Kane turns up to serve them slices of watermelon. Other details in the plot are mysterious and beautiful: a shot of Kane and her grandchildren seated on a bench and watching the moon; an entire sequence during the memorial service in which Clark and one of the boys observe in wonder a parade of ants.

“It’s the forbidden, forgotten image, the vision of the conquered that Akira Kurosawa offers us, which television — the Gulf war proves it again — is incapable of producing.” Writing in Cahiers du Cinéma last May, Frédéric Sabouraud put his finger on the moral choice exercised by Kurosawa in dealing with the impossible subject of nuclear holocaust. What Kurosawa seems to be saying in his final, powerful images is that no matter how much we care and how fast we run, we still can’t catch up with the truth of those who actually experienced the atomic bomb in Nagasaki.