It was shocking to learn that Harun Farocki (January 9, 1944 – July 30, 2014) died at the age of only 70. According to Artnet, he made over 90 films. He will be sorely missed.

From the Chicago Reader (February 14, 1992). — J.R.

FILMS BY HARUN FAROCKI

The paradox is that Farocki is probably more important as a writer than as a filmmaker, that his films are more written about than seen, and that instead of being a failing, this actually underlines his significance to the cinema today and his considerable role in the contemporary political avant-garde. . . . Only by turning itself into “writing” in the largest possible sense can film preserve itself as “a form of intelligence.”

— Thomas Elsaesser, 1983

The filmography of Harun Farocki — a German independent filmmaker, the son of an Islamic Indian doctor — spans 16 titles and 21 years. To the best of my knowledge, only one of his films (Between Two Wars) has ever shown in North America before now. A traveling group of 11 films put together by the Goethe-Institut began showing in Boston last November and this April will reach Houston, the last of the tour’s ten cities. Nine of the 11 films are currently showing at Chicago Filmmakers and I presume that the other two, both in 35-millimeter, aren’t showing because no 35-millimeter venue is available or willing to put them on. The larger question, however, is why it has taken so long for most of Farocki’s films to be seen on this side of the Atlantic. I would venture that this is because they belong to an intellectual and artistic tradition in Europe that has never taken hold on these shores — an approach to filmmaking that regards formal and political concerns as intimately intertwined and interdependent.

No film which only translates into film what is known already (from the newspaper, a book, TV) is worth anything. A film has to find an expression in its own language. — Harun Farocki

A relative recently asked me whatever happened to all the Marxist and communist friends I knew in Paris in the late 60s and early 70s. If I understood him correctly, the subtext of his question was that with the virtual collapse of European communism European communists and Marxists today must feel rather obsolete, made irrelevant by the forces of history.

What this question seems to overlook is that European Marxism encompasses a lot more than what Americans understand as “politics.” The aesthetics of most American Marxists and communists, at least within my lifetime, tend toward socialist realism and — more recently — multiculturalism. Turn to leftist American film magazines like Jump Cut and Cineaste, and you’ll find articles about third-world filmmakers, American independent documentarists, and old-style Hollywood lefties like Dalton Trumbo and Budd Schulberg. You’re less likely to find articles about more formally oriented filmmakers such as Farocki, Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, Jean-Luc Godard, Alexander Kluge, Jacques Rivette, Jacques Tati, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, but these are the filmmakers that the European Marxists and communists I know care passionately about.

The issue here isn’t so much the political leanings of these filmmakers: Bresson’s politics, which seldom figure directly in his work, are said to be right-wing; Tati was a petit bourgeois liberal at best; and Rivette hasn’t shown any leftist engagement since the 60s or 70s. But if, for instance, one was interested in artistic form in the 70s in France — in critical movements such as Russian formalism, or in the formal achievements of films ranging from Tati’s Playtime to Rivette’s Out 1 — one had to turn to communist critics like Noël Burch, Bernard Eisenschitz, or Jean-André Fieschi, and communist journals like La nouvelle critique, in order to read about it.

One reason why this fact seems worth stressing is that viewed superficially and solely in terms of their content some of Farocki’s best films might seem to be academic and even pedantic Marxist tracts. But in fact, much of this content is directly about form and the films’ formal properties are much subtler than they first appear. Take, for example, As You See (1986), which is showing tonight. A densely compacted essay film about technological and industrial history, As You See initially might seem to proceed in the manner of a slide lecture with a Marxist commentary. The film covers a vast amount of history and material ranging from ancient Egypt to the present. It begins with a drawing and a voiceover commentary spoken by the English translator Cynthia Beatt: “Here is a plow that looks like a cannon or a cannon that looks like a plow. The plowshare exists only to give the cannon a firm base. War is founded on earning one’s daily bread.” From here the film speeds past such subjects as an Egyptian hieroglyph combining a circle and cross (which is related to the formations of towns and forking paths), the invention and military uses of the machine and Maxim guns, highway cloverleafs, and the relation between transitional highway curves (which are compared to the cuts of butchers, who “respect anatomy”) and straight roads (which are connected to the concerns of surveyors and colonialists). (Over an aerial photograph of a roadway resembling a sinuous river, the narrator says, “Gazing at flowing water implies inner richness, but those who gaze at flowing traffic are considered stupid.”)

All these concerns, and many others that follow in the film, might be said to be political by virtue of being formal, and vice versa. Even the discussion of the machine gun might be said to follow this principle as it critiques the form of the weapon: “The military had 50 years to study what a machine gun is and they still sent soldiers out into machine-gun fire over and over again. They didn’t understand that one machine is more than a match for 1,000 men. Their way of breaking the machines was to send soldiers out into the line of fire.”

But, formally speaking, much more than just a linear and logical argument is being developed. While the above words are spoken, we hear the faint sounds of Brazilian drums and chants, also heard elsewhere in the film without any obvious correlation to the images or commentary. Periodically there are faint snatches of other kinds of music that seem to be employed in an aleatory manner (a technique that is also used effectively in Farocki’s subsequent essay film, Images of the World and the Inscription of War). It gradually becomes apparent that this essay is structured in some ways like a densely plotted narrative: certain themes and subjects that originally seem to have no logical relation to the argument crop up later more legibly, like peripheral characters who eventually become integrated into a story. Other images — such as shots of actors dubbing a German porn film — are never directly alluded to in the commentary, and one has to grasp their significance formally, poetically, and metaphorically (if at all).

As Thomas Elsaesser argues, Farocki may be more important as a writer than as a filmmaker. But it’s important to note that the “writing” that matters most in As You See, Images of the World and the Inscription of War, and How to Live in the Federal Republic of Germany — all of which were made after Elsaesser published his essay — is indistinguishable from the filmmaking. On one level, the first two of these films are narrations with illustrations, and the third is a series of illustrations — scenes taken from instructional classes and therapy and test sessions involving simulations and exercises — that require no narration because the juxtapositions and intercutting between them say everything (and say it with devastating impact). On this level, all three films pursue ambitious and multifaceted intellectual arguments, and in each case the argument is perfectly described by the film’s title. But on another level, these three films are mysterious, provocative, and even beautiful formal constructions that say far more.

Film was discovered too late. The art-mathematicians of the Renaissance should have discovered it, it would have helped them in measuring man and space. It would have flourished during the Enlightenment when one was able to believe that concept could be arrived at through visual perception (viewing), and that what is understandable could be made visible. When film was finally discovered, science was beyond the imaginable (the presentable). He who tries to imagine the theory of relativity suffers from misconceptions. — Harun Farocki

What seems especially regrettable about the absence of Farocki’s two 35- millimeter films — Before Your Eyes — Vietnam (1981) and Betrayed (1985) — from the Chicago retrospective is that, judging from the eight Farocki films I have seen, his recent work is much more interesting and complex than his early shorts. While the early shorts aren’t devoid of interest, they bear heavy traces of Godard’s and Straub- Huillet’s influence and show relatively few signs of either the intellectual density of As You See and Images of the World and the Inscription of War (1989) or the conceptual clarity of The Taste of Life (1979), An Image (1983), and How to Live in the Federal Republic of Germany (1990). (Apparently his first feature, Between Two Wars — an essay film completed in 1977 — which concludes the local retrospective Saturday night, escapes some of these strictures.)

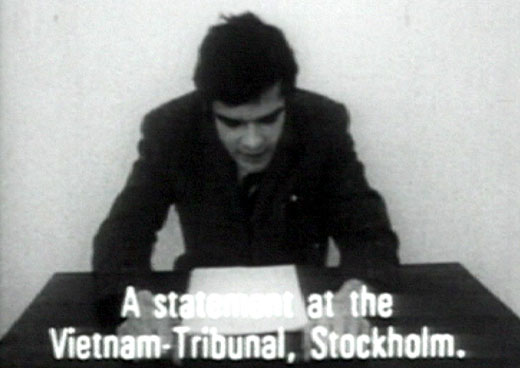

The Words of the Chairman (1967), Inextinguishable Fire (1969), and The Division of All Days (1970) are all black-and-white shorts concerned with issues of representation in relation to political subjects. The first — only two minutes long and narrated by fellow German independent Helke Sander — is a rather jokey reflection on then-current Maoism, made the same year as Godard’s La chinoise and oriented around the notion that Chairman Mao’s words may become weapons, but they exist only on paper.

Inextinguishable Fire offers a minimalist but precise 22 minutes on the subject of the manufacture and effects of napalm — a salutary subject at the present moment, when Francis Coppola’s and Oliver Stone’s morally anguished beads of sweat are deemed to be of far greater historical importance. A chilling moment occurs near the beginning, when a man tonelessly reading the testimony of a Vietnamese victim suddenly extinguishes a cigarette on his forearm. He then calmly explains that the temperature of napalm is seven and a half times greater than the temperature of that lit cigarette. Most of the remainder of the film is informative but anticlimactic.

The 40-minute The Division of All Days — a dry Marxist analysis of capitalist exploitation with occasional sarcastic asides, cowritten and codirected by Hartmut Bitomsky — is the least interesting Farocki film I’ve seen. Unless I missed something, I’m afraid that adjectives such as “dour” and “pedantic” that have been applied unjustly to his subsequent works are more to the point here.

In striking contrast, The Taste of Life, a half-hour color documentary made the same year, is the most lyrical and “open” of all the Farocki films I’ve seen. A series of street scenes — some shown silently, some with sync sound — proceeds musically with variations around certain themes. The film opens with a series of identically framed shots of different adults and children stopping to examine the damage done to a car’s headlights in a collision; we see neither the collision nor the headlights, so the musical structure is mainly built around the ways various people crouch by, point at, and study the front of the car. A more extended motif is shot in front of a newsagent’s shop. We see the shop around opening time, on separate days, as a woman emerges carrying signs that advertise the headlines of different newspapers. There are two stretches of untranslated narration in this short that I couldn’t follow, and these might well add significantly to the film’s meaning, but even without this textual element, the film is a pleasure to watch and listen to.

An Image, another half-hour color documentary, is devoted to the construction of one centerfold photo, shot over a single day in Playboy‘s Munich studio. I mean “construction” literally: the film begins with the building of the set and the placement of props, then proceeds through the diverse poses and rearrangements of the model, complete with the photographer’s instructions (“Give us your usual saucy look”), followed by various critiques and conferences about the test photos and various reshoots before the lights are extinguished and the set is dismantled.

A materialist documentary in the best sense of the word, An Image provides a fascinating contrast with the artist-and-model sessions in Rivette’s recent La belle noiseuse. As in the Rivette film, many others besides the artist and the model are involved in the construction of the image, but here the others (many of them women) are visibly participating in its creation, and the ideological construction taking place is as evident as the various kinds of labor involved. Here industrial history and analysis — the explicit subject of many of Farocki’s films, and the implicit subject of many others — inform our basic understanding of how porn is manufactured, while incidentally providing us with some clues about how the porn dubbing sessions in As You See link up with some of that film’s other industrial subjects.

“The history of technology is fond of describing the route that development has taken from a to b,” the narrator says at a key juncture in As You See. “It should describe which alternatives there were and who rejected them.” The same thing might be said of the history of art, including the history of cinema. From this standpoint, the work of Harun Farocki — strategically positioned outside the history of cinema as it’s usually written — represents a tantalizing and exciting intellectual alternative, a road not taken.