From the Chicago Reader (May 3, 1991). — J.R.

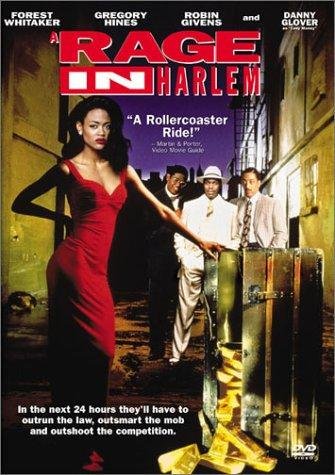

A RAGE IN HARLEM

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Bill Duke

Written by John Toles-Bey and Bobby Crawford

With Forest Whitaker, Gregory Hines, Robin Givens, Zakes Mokae, Danny Glover, Badja Djola, and John Toles-Bey.

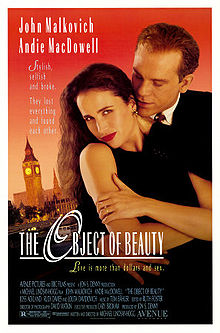

THE OBJECT OF BEAUTY

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Michael Lindsay-Hogg

With John Malkovich, Andie MacDowell, Joss Ackland, Rudi Davies, Peter Riegert, Lolita Davidovich, and Ricci Harnett.

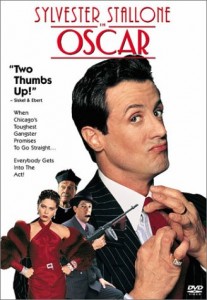

OSCAR

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by John Landis

Written by Michael Barrie and Jim Mulholland

With Sylvester Stallone, Peter Riegert, Joey Travolta, Elizabeth Barondes, Tim Curry, Vincent Spano, Ornella Muti, and Joycelyn O’Brien.

With at least three new comedies around at the moment — four counting the semicomic Impromptu — it seems like the silly season is fully upon us. Although the three urban comedies under review are set in different decades (Oscar in the 30s, A Rage in Harlem in the 50s, The Object of Beauty in the present), they all appear at first to be equally concerned with money — the thing that keeps the wheels of their complicated farcical plots turning. All have something to do with sex and romance as well, but it’s clearly money that holds the sex and romance in place. And all three abound in characters whose greed and preoccupation with money offset the innocent purity of other characters — a religious and unworldly undertaker (Forest Whitaker in A Rage in Harlem), a deaf-mute cleaning lady with an apparent taste for art (Rudi Davies in The Object of Beauty), and an elocutionist who lives with his mother (Tim Curry in Oscar).

Significantly, however, only The Object of Beauty — an English comedy with American stars — actually settles on money and its effects as its true subject; the other two ultimately use money more as an excuse for delving into other matters. Conversely, innocence in The Object of Beauty turns out to be more of a theoretical construct than in the other two pictures; as a subject in its own right, it barely seems to exist at all.

Innocence is of course a staple of comedy, but our definition of what constitutes appealing innocence varies from period to period and country to country, and any contemporary comedy that fails to match an audience’s expectations in this regard is bound to be in trouble. It seems to me, for example, that the antipathy that often currently greets the image of the holy fool and spastic bumbler established by Jerry Lewis in the 50s and 60s has something to do with the painful accuracy of that image as an index of the traumatic adolescence of the American character. (Critic Raymond Durgnat once pinpointed one aspect of this connection by referring to Lewis as “the anti-James Dean.”) Lewis clearly benefited from that image as long as his early fans were children who could readily recognize parts of themselves in Lewis’s behavior; but once many of these children grew older and had to confront the implications of that behavior in more grown-up terms, their affection tended to sour — largely, I think, because the arrested development they saw in Lewis was a source of embarrassment. Any sustained identification with his behavior entailed accepting a degree of helplessness that was incompatible with America’s self-image, particularly in terms of masculinity.

Forest Whitaker does a good job of emulating Lewis in A Rage in Harlem, and one reason his imitation seems substantially less threatening than its model is the different set of associations Whitaker carries with him. This film also deals with sexuality in a way that Lewis films never do. It’s hard to imagine a sexual encounter between Lewis and Marilyn Monroe in a 50s picture (Monroe’s scenes with Tommy Noonan in Gentlemen Prefer Blondes are about the closest we get to this), but Whitaker’s scenes with Robin Givens — who suggests Monroe’s bombshell as much as Whitaker suggests Lewis’s fumbling innocent — show us some of the dynamics that such an encounter would have taken. It’s a pretty volatile combo.

These two star performances aren’t the only ones that give A Rage in Harlem spirit and energy; Gregory Hines does a good job as a street hustler, and Danny Glover plays a sinister, amiable crook named Easy Money, who carries a fluffy little dog with him everywhere he goes — a variation on the sort of black-comic part that Richard Widmark used to excel at in the 50s, most notably in Kiss of Death.

These memories of 50s Hollywood movies — the film is an adaptation of a Chester Himes crime novel published in 1957 — help director Bill Duke and writers John Toles-Bey and Bobby Crawford establish the period ambience, as do the well-chosen Cincinnati locations. The only limitation in the overall portraiture is a relative failure to distinguish between the speech patterns and attitudes of southern and nonsouthern black characters — a characteristic oversight in recent movies involving blacks (one also finds it in The Long Walk Home, though To Sleep With Anger pointedly and brilliantly avoids it). The fact that Givens’s street-smart character comes from Mississippi while Whitaker’s naive and inexperienced undertaker lives in Harlem suggests a rather fresh contrast in styles and views — a reversal of country bumpkin and city-slicker archetypes — that might have been used to enhance their comic encounters.

The movie has a relatively routine plot about a treasure chest full of gold stolen (in the precredits sequence) in Natchez, Mississippi, that turns up in Harlem. But what gives it life is the broad range of characters and character acting such a story permits — rarely have so many talented black actors been allowed so much leeway to show what they can do. A Rage in Harlem will be showing in competition at the Cannes film festival this month, along with Spike Lee’s still-unreleased Jungle Fever. Combine these films with The Five Heartbearts and last year’s To Sleep With Anger and you can see that a commercial black American cinema worthy of the name — free of the traditional tokenism and “special handling” that has dogged its progress — may finally have a chance to emerge, if enough people see these films.

The problem with the innocent character in The Object of Beauty — a chambermaid in London who swipes a small bronze Henry Moore sculpture from the hotel suite occupied by an American couple (John Malkovich and Andie MacDowell), thereby setting the plot in motion — is that, properly speaking, she doesn’t exist as a character at all. Writer-director Michael Lindsay-Hogg seems to make her a deaf-mute because he can’t imagine what she would say if she could speak; her speechlessness virtually defines her and has a lot to do with her status as an incompletely realized character.

The American couple are shallow and self-centered, conspicuous consumers, but as we discover in the witty opening scene — when Malkovich’s gold card is rejected in a plush restaurant — they’re seriously strapped for cash, unable even to pay their hotel bill. Before long they’re seriously considering using the bronze — an anniversary present from MacDowell’s now-estranged husband (Peter Riegert) — to get out of their jam. Malkovich suggests auctioning it off; MacDowell rejects this idea and later proposes that they pretend it’s been stolen in order to collect the insurance. When the maid steals the bronze, the couple’s mutual trust starts to erode as each suspects the other of surreptitiously making off with it.

Part of the satiric point of the movie is that the maid is the only one who really appreciates the bronze as an “object of beauty”; everyone else — from the couple to the rest of the hotel staff to the insurance people to the maid’s punk brother to the fence her brother knows — sees it chiefly as a source of money. The maid becomes a litmus test for the venality of others: she is hired by the cynical hotel manager (Joss Ackland at his funniest) only after the social worker who represents her threatens him with blackmail — a story in the press about the hotel’s unwillingness to hire the handicapped. And her adoration of the bronze is clearly meant to stand apart from the coarser motives of everyone else. But it isn’t until quite late in the film that the purity of her motives is spelled out. When an insurance man asks her why she stole the sculpture, she writes her answer on a piece of paper: “Because it spoke and I heard it.”

Apart from this single and belated mystical utterance, the maid is kept mum because the story has no interest in her aside from her function as a contrast to everyone else. Curiously, Stuart Klawans in the Nation finds this limitation praiseworthy: “What’s wonderfully, bracingly disturbing is that the film comes down firmly on [the American couple’s] side. The more objectionable their behavior, the more sympathetic they become. Not that the film is unsympathetic toward the chambermaid . . . but it’s unsentimental enough to crush her. She’s the sort of person who has never had a break in her life, and the movie isn’t about to disrupt that pattern.”

Klawans seems to be saying that this movie lays bare the audience’s exclusive interest in the shallow couple and their shallow milieu by revealing that neither the film nor its audience is seriously interested in the moral alternative posed by the maid. Maybe so, but does this make the movie interesting? The problem with Lindsay-Hogg’s facile cynicism is that it keeps the movie in motion only as long as the fates of the couple and the bronze are unresolved; everything comes to a halt as soon as the monetary problems are overcome — which is largely why the film’s final scene seems so flat and enervated.

Missing from Klawans’s formulation, moreover, is the peculiarly British mixture of envy and ridicule expressed by the film toward the American couple and the glamour they represent. The film makes fun of this ambivalence when it crops up in some of the British characters; nevertheless, it isn’t sufficiently confident about its own moral and conceptual position to express any sustained independence from that ambivalence. The American couple are seen through so much resentment that any trait that doesn’t match their surface behavior tends to get short shrift. Perhaps the weakest moment in Malkovich’s generally fine and inventive performance is when he calls his parents in New Jersey to ask for money and their implied indifference prevents him from making his pitch — and it’s the script that lets him down. The scene is clearly meant to point up the “truth” of Malkovich’s shaky self-confidence that his smooth drawing-room manner is designed to conceal, but when it comes to examining hidden depths, the script is almost as shaky with this character as it is with the maid.

Surface effects are all the movie knows, though on this level Lindsay-Hogg’s script and direction — amply served by the talents of the cast — are a pleasure to follow. It’s only when the larger satirical picture looms into view that the edges of the class portraiture become blurry.

However inadequately realized it may be in this larger sense, Lindsay-Hogg’s movie at least has a subject. Whatever subject Oscar may once have had in its preproduction phases, it no longer registers — unless it’s Sylvester Stallone’s blunderbuss determination to impose himself as a comic actor (as opposed to, say, a comic presence).

A package in the worst sense, this movie is yet another American remake of a French boulevard farce — a 1967 Louis de Funes vehicle directed by Edouard Molinaro — that mechanically aims to be about as broad as a barn door and pretty much succeeds, but without generating much humor. The story concerns a well-to-do Prohibition gangster (Stallone) who promises his dying father (Kirk Douglas) in a precredits sequence that he’ll go straight, and then spends the remainder of the movie trying to live up to his promise, while getting into endless complications with his vast entourage — his accountant (Vincent Spano), his various henchmen (among others, Peter Riegert again), his servants (including Joycelyn O’Brien), his elocution instructor (Tim Curry), and his wife and daughter (Ornella Muti and Marisa Tomei), as well as other flunkies too numerous to mention.

An uneven director at best, John Landis usually combines a sense of comic innocence and sweetness with a tendency to overproduce and physically inflate his comic terrains, a combination that probably paid off best in The Blues Brothers. Here the only sweet and innocent character is the talented and chameleonlike Tim Curry, but even he often seems crushed by the leaden comic pacing and the physical layout — a gaudy mansion that often seems as swollen as a circus tent. And Stallone’s habit of pausing after every grimace and gag line, apparently because he expects them to be greeted by extended gales of laughter, turns much of the movie into a kind of slow-motion nightmare in which the other actors often seem to be standing about and gaping uncomfortably, waiting for their cues.

Landis, in an apparent effort to distract us from these awkward pauses — which he seems either unwilling or unable to eliminate (to all appearances Stallone is running the show) — hypes the rest of the action with such unnatural frenzy that the various would-be comic motifs (including Tomei’s crying jags and the endless substitutions of bags containing money and women’s underwear) have all the subtlety of avalanches landing in your lap. I recommend it as a perfect cure for insomnia.