This was written for the January 26, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader, a good five years before the premiere of at least one of my absolute favorite Akerman films: her non-fictional From the East (see the first photograph below; just below that is a smaller still from her subsequent From the Other Side in 2002, which isn’t exactly chopped liver either ). But in fact there were many high points and wonders from Akerman since then. — J.R.

THE FILMS OF CHANTAL AKERMAN

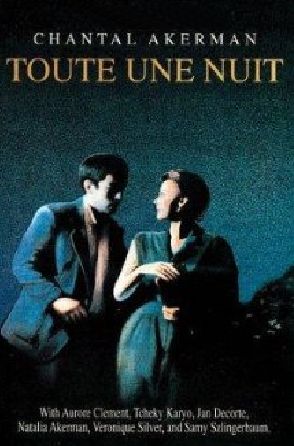

On one hand, the films of the 39-year-old Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman are about as varied as anyone could wish. Some are in 16-millimeter and some are in 35; some are narrative and some are nonnarrative; the running times range from 11 minutes to 205. The genres range from autobiography to personal psychodrama to domestic drama to comedy to musical to documentary to feature-in-progress — a span that still fails to include a silent, not-exactly-documentary study of a run-down New York hotel (Hotel Monterey), a vast collection of miniplots covering a single night in a city (Toute une nuit), and a feature-length string of Jewish jokes recited by immigrants in Brooklyn exteriors (Food, Family and Philosophy), among other oddities.

On the other hand, paradoxically, there are few important contemporary filmmakers whose range is as ruthlessly narrow as Akerman’s, formally and emotionally. Virtually all of her films, regardless of genre, come across as melancholy, narcissistic meditations charged with feelings of loneliness and anxiety; and nearly all of them have the same hard-edged painterly presence and monumentality, the same precise sense of framing, locations, and empty space. Most of them are fundamentally concerned with the discomfort of bodies in rooms. (Akerman is basically geared toward interiors, which may be one reason her latest feature, Food, Family and Philosophy, set mostly in exteriors, is not one of her strongest. The fact that virtually all of Window Shopping, her musical, is set inside a shopping mall sets up an interesting ambiguity about whether one is inside or out — until the shock of the ending, when the film finally moves out into the open air.)

Her movies generally rely quite a bit on real time (as opposed to film time), and although her sound tracks tend to be constructed in layers rather than randomly recorded, none of them, with the exception of Window Shopping, uses offscreen music. Finally, a good many of her movies qualify as remakes of her earlier works: Jeanne Dielman, her longest film, can be regarded as a remake of Saute ma ville, her first film and one of her shortest; and the medium-length The Man With a Suitcase can be seen as a remake of Jeanne Dielman. Similarly, from a certain standpoint, Les rendezvous d’Anna is a remake of Je tu il elle, and, to a lesser extent, Food, Family and Philosophy is a remake of Toute une nuit.

The Akerman retrospective that started at Facets Multimedia Center earlier this month and concludes in early February isn’t quite exhaustive: probably the most significant omissions, currently unavailable in the U.S., are Dis-moi (1980), The Man With a Suitcase (1984), and her most recent feature, Food, Family and Philosophy, aka Histoires d’Amérique (1988). (An uncharacteristic and fairly conventional documentary about Pina Bausch and her dance company, One Day Pina Asked . . ., also made in 1984, which turned up on cable a few years ago, is also missing.) Nevertheless, this is the most complete presentation of Akerman’s work that Chicagoans are likely to get in the foreseeable future. And considering both the importance of her work and its general scarcity in the U.S. — none of her films, for example, has yet made it onto video — interested viewers should brave the risk of uneven and/or calamitous projection that plagues Facets screenings and check this filmmaker out. Whether you love or hate her work, I can guarantee you won’t find anything else remotely like it playing anywhere else; and three of her very best films — Window Shopping, Toute une nuit, and her masterpiece, Jeanne Dielman — are showing this week.

There are, however, two potential obstacles to appreciating Akerman’s films that might be mitigated by a discussion of them. The first has to do with the role of a director and how it’s perceived. It’s widely believed, with some justice, that film criticism and appreciation in general made a significant step forward when the French term mise en scène was introduced in this country in the 60s, largely through the writing of Andrew Sarris. Becoming aware of the director, or metteur en scène, meant becoming aware of a director’s style and vision, and even though Sarris’s adoption of the term needlessly added hyphens to the French — giving “mise-en-scène” a certain mystical flavor in English which it retains even today — the term has added something of value to our overall conception of cinema.

Mise en scène literally means “place on the stage,” making us aware that it is the director who places the actors, the décor, and the camera in relation to one another. It is the stage of filmmaking that takes place after the writing of the script, during the shooting, and before the editing, and because the commercial Hollywood cinema tends to break up these three activities according to a strict division of labor, the importance of mise en scène as a creative concept is that it is distinct from both of the other processes.

But there is another French term, in some ways an even more important one, that has never crossed the Atlantic to enter common usage in the U.S., in part because the concept behind it is a little more difficult to grasp: découpage. In terms of its popular French usage, it has three separate but interlocking meanings: the final form of a script, the breakdown of a film into separate shots and sequences prior to filming, and the basic structure of a finished film. (The verb découper means “to cut out” or “to cut up.”) The term découpage implies that there is a continuity between script and editing — a continuity imposed not by a writer, director, or editor, but by a filmmaker who carries the project through from beginning to end — and that mise en scène becomes a means toward an end in this continuity rather than an end in itself.

If the term mise en scène implies an industrial model of cinema, the term découpage implies an artistic or artisanal model. The latter term makes sense in France, where a filmmaker’s right to final cut is a part of actual law; it makes very little sense in a country like ours, where even the writer-directors who have an unusual amount of creative freedom — Woody Allen, for instance — do not produce a découpage in the sense that Robert Bresson does. (As we know from Ralph Rosenblum and Robert Karen’s book When the Shooting Stops . . . the Cutting Begins, practically all of Allen’s features are restructured and re-created in the cutting room, and the original scripts are quite different from the finished products.)

In this context it is misleading to talk merely about Akerman’s mise en scène in spite of her close attention to framing, because from that vantage point, many of her movies look rather anemic. It’s her découpage that matters — that is, not only what happens in her shots but what happens between them, among them, across them, and through them. (The same thing applies to practically all of the most important filmmakers in the history of movies: Carl Dreyer, Sergei Eisenstein, Alfred Hitchcock, Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, Jean Renoir, and Orson Welles may be known to us as master directors, but their art is ultimately the art of découpage rather than simply mise en scène.) Consequently, comparing Akerman to someone like Woody Allen, Susan Seidelman, Paul Mazursky, or Steven Soderbergh on the level of “mise en scène” is about as meaningless as comparing a microscope to a microwave, or a minimalist artist to an entertainer.

The second obstacle to appreciating Akerman’s films has to do with Akerman’s being a Belgian Jew—though she has spent extended periods of her adult life and shot several of her films in both France and the U.S. Most of her films are in French, and it has been all too easy for many critics to discuss her work as if it were essentially part of the French cinema; but it’s an impulse that should be firmly resisted. The cultural dominance of France and the U.S. in relation to such countries as Belgium, Switzerland, and Canada has led to a streak of cultural imperalism that confuses our understanding of filmmakers as important as Michael Snow (Canadian) and Jean-Luc Godard (Swiss) as well as Akerman.

The fact that Snow made his best-known film, Wavelength, in a Manhattan loft and that Godard made many of his best-known features in France obviously adds to this confusion, and at the same time it falsely enhances the reputations of these filmmakers by seeming to make them more fashionable. It’s been argued more than once that if Wavelength had been shot in, say, a Toronto loft, it might never have been so important to many Manhattan critics, and it’s worth adding that the period when Godard was most fashionable coincided with the period when he was based in Paris; now that he’s based in the vicinity of Lausanne, Switzerland, his work is generally considered a good deal more perverse and impenetrable.

The main point to be stressed here is that because she is both Belgian and Jewish, Akerman has a stance that is essentially that of an outsider in an international context. While it is possible to link her work to that of a few other, much lesser known Belgian independents — such as Samy Szlingerbaum, with whom she collaborated on one of her earliest films, the hardly ever shown Le 15/8 (1973) — and to see connections with a few Belgian painters (most notably Paul Delvaux, whose surrealist night scenes bear an eerie resemblance to some of her shots), it is probably even more pertinent to note the degree to which exile is a recurring theme in her work. (Major examples would include News From Home, Les rendezvous d’Anna, Toute une nuit, The Man With a Suitcase, Window Shopping, and Food, Family and Philosophy.)

***

Does one’s integrity ever lie in what he is not able to do? I think that usually it does, for free will does not mean one will, but many wills conflicting in one man. — Flannery O’Connor

If I have a reputation for being difficult, it’s because I love the everyday and want to present it. In general people go to the movies precisely to escape the everyday. — Chantal Akerman

A yearning for the ordinary as well as the everyday runs through Akerman’s work like a recurring, plaintive refrain. It is a longing that takes many forms: part of it is simply her ambition to make a commercially successful movie; another part is the desire of a self-destructive, somewhat regressive neurotic — Akerman herself in Saute ma ville, Je tu il elle, and The Man With a Suitcase; Delphine Seyrig in Jeanne Dielman; Aurore Clement in Les rendezvous d’Anna — to go legit and be like “normal” people. Je tu il elle and Les rendezvous d’Anna both feature a bisexual heroine who wants to either resolve an unhappy relationship with another woman or to go straight; in Saute ma ville, Je tu il elle, Jeanne Dielman, and The Man With a Suitcase, the desire to be “normal” is largely reflected in the efforts of the heroine simply to inhabit a domestic space.

This desire for normalcy accounts for much of the difficulty of assimilating Akerman’s work to any political program, feminist or otherwise. As an account of domestic oppression and repression, Jeanne Dielman — whose full title is Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai de Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles — largely escapes these strictures, and Akerman herself has admitted that this film can be regarded as feminist. But she has been less willing to let her other works be viewed in a political context — she once refused to let Je tu il elle be shown in a gay and lesbian film festival — denying that she considers herself a feminist filmmaker, despite the efforts of certain feminist film critics to claim her as one.

The two most extreme expressions of neurotic regression in Akerman’s work are probably the first third of Je tu il elle and the last half of The Man With a Suitcase, both of which show Akerman herself alone in a room, steadily growing crazier and crazier over several days. In Je tu il elle she compulsively rearranges her few items of furniture, eats only from a bag of sugar, writes and rewrites a letter to a real or potential boyfriend (rearranging the various drafts in a series of piles like a game of solitaire), and takes off her clothes and drapes them over her body like bed sheets. In the more comic The Man With a Suitcase, made ten years later, in which she is sharing an apartment with a young American man she hardly knows, she barricades herself in a single room and sets up a TV camera by the window to monitor his comings and goings.

Perhaps the most extreme evocations of “normality” in Akerman’s work are the many heterosexual couples seen in Toute une nuit and Window Shopping. And somewhere in between are the formidable figures of Jeanne Dielman, a widow and compulsive housekeeper who turns tricks with male clients in the afternoons, and Anna in Les rendezvous d’Anna, a Belgian filmmaker traveling on the train from Cologne to Paris via Brussels and making various stops on the way. One token of Anna’s in-betweenness is her visit with her mother, played by Léa Massari, in Brussels. Instead of going home, where Anna’s ailing father is already asleep, they check into a cheap hotel room where Anna, lying naked beside her mother in bed, calmly describes a lesbian affair she has recently become involved in. (Her lover is never seen in the film, but she’s heard on Anna’s answering machine when she returns to Paris; and, to complicate matters, the voice is Akerman’s.)

Considering Akerman’s craving to make a commercially successful film, it’s ironic that she gave the same French title, Les années 80, to both a feature-length preview of the musical she was trying to raise money for in 1983 (shown here as The Golden Eighties) and the finished musical that she finally made three years later (known in English as Window Shopping) — which certainly didn’t help matters much. It’s no less ironic that the preview — which consists of an hour of videotaped auditions with actresses, followed by 25 minutes of sample scenes from the movie in 35-millimeter — proves in many ways to be more emotionally affecting than the completed work. (If memory serves, these sample scenes aren’t included in Window Shopping because Akerman wound up making cast changes in the interim, although the same catchy songs — with music by Marc Herouet and lyrics by Akerman — are heard in both.)

A noble failure, Window Shopping is a musical inspired not so much by Hollywood as by some of the films of Jacques Demy — chiefly Lola, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and The Young Girls of Rochefort — which are themselves inspired by Hollywood. Composed of several intersecting stories about romances that occur between various workers and customers at a shopping mall, the movie evokes Demy in emotional tone and plotting rather than in filmmaking style: a character named Sylvie pining away for her boyfriend in Montréal directly evokes the heroine of Lola, while the fortuitous encounter in the mall of a middle-aged couple who haven’t seen each other in 30 years — an American (John Berry) and a Polish refugee (Delphine Seyrig) who now runs a boutique in the mall with her husband (Charles Denner) — harks back to The Young Girls of Rochefort.

Major differences include Akerman’s occasional use of characters — such as a youthful male quartet that suggests a French version of the Hi-Los — singing directly to the camera, and her avoidance of dancing, as well as an overall klutziness in the songs’ staging that often results in simple weirdness rather than the charm of Demy’s numbers. (No choreographer is listed in the credits, and the few desultory dance moves that are introduced in a number in a beauty salon are even clunkier than those in a similar setting in Spike Lee’s School Daze.)

The main problem with Window Shopping is that in spite of the power of the songs and the appeal of many of the performers, the movie as a whole proves to be rather uninvolving. The dialogue sequences are rather flat, and Akerman’s attempts to breathe life into her musical-comedy characters — which can be quite moving when we see her making that effort in The Golden Eighties — prove to be more compelling than the final results of her work.

There is something heroic about this failure, however, because in keeping with Flannery O’Connor’s statement quoted above, part of Akerman’s integrity as an artist consists of what she is not able to do. The yearning for romance and for the romance of the ordinary is a central ingredient of her work, but the most remarkable moments in her films are those in which her other, demonic impulses rebel against this fantasy. Emblematic in this respect is the ending of Toute une nuit, an insomniac’s movie about insomniacs, in which a couple’s lovemaking is gradually smothered, and all but obliterated from our attention, by the hectoring sounds of early-morning traffic outside. The tortured aggressiveness of such a moment is finally what her filmmaking is all about — her cold, elegantly symmetrical compositions and brutal sounds being hammered into our skulls with an obstinate will to power that makes Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sam Peckinpah, and Clint Eastwood all seem like pussycats.