From the Chicago Reader (September 23, 1988). — J.R.

1. A front-page story in the August 24 Variety begins, “Last week’s Republican National Convention garnered the worst network ratings of any convention in TV history.” An interesting piece of information, but not, as far as I know, one that was noted in daily newspapers, weekly newsmagazines, or on TV. Why does one have to go to Variety to discover this morsel of recent history? Perhaps it has something to do with Variety‘s status as a trade journal. Mainstream print and TV journalism may be part of the entertainment business, but they’re not generally about entertainment in the sense that a publication like Variety is.

The story in Variety goes on to report that both of this summer’s political conventions significantly boosted video rentals; a couple of large video rental chains reported increases in business between 30 and 57 percent. Do we interpret this as an opting for entertainment over news coverage, or as a preference for one kind of entertainment over another? Do we read it as a sign of desperate cynicism, or as a sign of healthy liberation? Or, if we read it as the latter, was it liberation only from the standard TV shows that the conventions were preempting?

According to contemporary parlance, it degrades a presidential campaign to regard it simply as entertainment, but validates a movie to regard it the same way. But with show biz equally operative and pertinent in both spheres, we do ourselves a certain disservice when we make these hard distinctions. Both movies and presidential candidates are designed to tell us what we want to hear — a task they perform either well or badly. As Richard Dyer points out in his essay “Entertainment and Utopia,” “Two of the taken-for-granted descriptions of entertainment, as ‘escape’ and as ‘wish-fulfillment,’ point to its central thrust, namely, utopianism.” And this utopianism, Dyer adds, “presents, head-on as it were, what utopia would feel like rather than how it would be organized.”

2. It may be a partial legacy of the Puritan work ethic that making money is not regarded in our society as any sort of escape. So little, in fact, is it currently considered a form of escape that virtually every other activity that fills our lives — eating, reading, thinking, sleeping, bathing, having sex, exercising, watching TV, talking to friends or relatives, going to movies, getting drunk or stoned — is considered a form of escape, an escape from making money and whatever that entails. Some of these “secondary” activities are treated with more respect than others, but they all generally take a back-seat to what most of us consider the main order of the day, which is going to work.

3. Entertainment is often defined in our minds by what it isn’t. “The life of Jesus isn’t entertainment,” read one of the placards in front of the Biograph a few weeks ago (or words to that effect), in protest of The Last Temptation of Christ. Another placard read, “God doesn’t like this movie.” Does that mean that God wasn’t entertained by it?

Roger Ebert recently objected on television to a scene in Betrayed in which a black man is hunted down for sport by a group of white racists. Citing the unpleasantness of this scene as a major reason why he didn’t like the movie, Ebert argued — again, I rely on memory — that it didn’t belong in a piece of Hollywood entertainment.

If we often define entertainment according to what it isn’t, our list of negatives may be almost as long as our list of escapes from making money: Entertainment isn’t art. (Art makes us nervous, usually requires dressing up, and, worst of all, is taught to us in school and is a risky way of making money.) Entertainment isn’t religion. Entertainment isn’t philosophy. Entertainment isn’t politics. Entertainment certainly isn’t making money. And for some people, entertainment isn’t thought, either. “I go to movies to relax and be en tertained,” a call-in listener remarked on Milt Rosenberg’s radio talk show Extension 720 last month. “If I want to think, I listen to your show.” (When nudged, however, she admitted that Extension 720 was relaxing, too.)

4. The French are fond of using the word “pleasure” a little bit like the way we use the word “entertainment.” One advantage to “pleasure” is that it implies commitment rather than distraction, and doesn’t create a pejorative dichotomy between art (serious) and entertainment (nonserious). When entertainment is defined as a form of relaxation, or at least closely associated with that experience, the implication is that an absence of excitement or passionate feeling is as important to the experience as an absence of thought. (Ronald Reagan, by this criterion, is entertainment, not art.)

5. What is the stereotypical desire of the hardworking capitalist who comes home from a long day at work carving up his or her neighbors and wants a little peace and quiet? To unwind, relax, take it easy; take a bath, read the paper, see a show. To forget the world and the bloodbath one’s left behind and think about something else for a change.

The problem is, all of us, even the bloodthirstiest capitalists, cheat on this premise. People don’t stand in line to see movies like Who Framed Roger Rabbit, A Fish Called Wanda, A Nightmare on Elm Street 4: The Dream Master, or Die Hard with the intention of being put to sleep by them. One thing that these four box-office hits have in common is that they’re frenetic; their action is defined by catastrophes and they’re populated largely by manic types. To call them utopian may not be wholly inaccurate, but it doesn’t get us very far in describing what it’s like on an immediate level to watch them. Almost going to hell in a handbasket is what most of the characters in these movies seem to be doing. Are narrow escapes from oblivion and destruction the only form of utopia available to us — perhaps because we’re too jaded to believe in any others? It’s a commercial trend, in any case, that has been with us at least since The Terminator (1984) — a movie that postulated apocalypse as a prerequisite for a happy ending.

6. “Movies are your best form of entertainment,” the old advertising slogan goes. You can be pretty sure that no one would ever think to claim, “Films are your best form of entertainment,” because films, as opposed to movies, are supposed to be “serious” — works of art, documentaries about important issues, foreign works with subtitles: rarefied and more upscale kinds of experience.

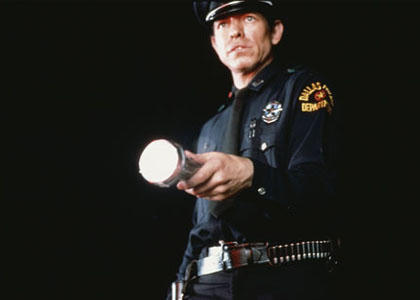

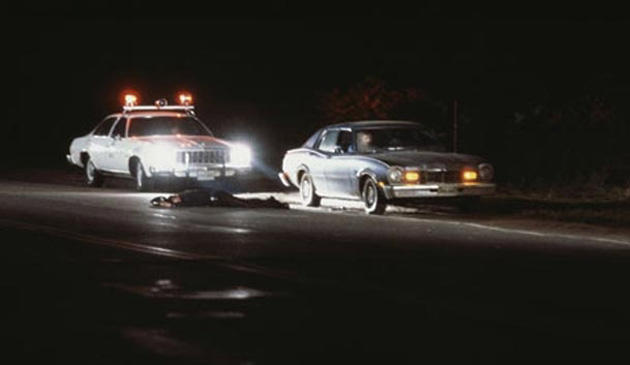

Errol Morris’s new feature, The Thin Blue Line, playing this week at the Music Box, is a good case in point because it manages to straddle these categories in a more obvious way than most other independent efforts. Even though it deals with real people and real events — those surrounding the murder of a Dallas cop in 1976 — as well as diverse speculations about them, the distributors are careful to refer to it as a “nonfiction” feature as opposed to a documentary, possibly so as not to scare away those who assume that it’s a “film” rather than a “movie.” According to the press materials, it “establishes a new genre in the tradition of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood” — a good example of a work that combines (or confuses) serious and nonserious categories in order to offer something for everyone (as they used to say in the 60s, different strokes for different folks).

Speaking for myself, I happen to find The Thin Blue Line entertaining — as a movie and as a film — in spite of the fact that it tries to do so much with its subject, metaphysically as well as journalistically, “entertainingly” as well as “seriously,” that it winds up as a work peculiarly divided against itself.

Included in the press materials for the film is an article by Morris that focuses on all the major facts and aspects of his subject that he decided to leave out of his feature, and in a way this supplementary data is every bit as absorbing as what he left in. The problem is, what’s entertaining about the movie — the fanciful re-creations of the crime, Philip Glass’s score, the handsome minimalist compositions, the film noir references, the callow Texas accents that we’re invited to laugh at in a superior manner — all intermittently work against the film’s efforts to be a serious social statement.

This isn’t to say that art (or entertainment) and social purpose always have to be in conflict with one another (think of Chaplin or Tati) — only that Morris hasn’t worked out a way that allows them consistently to serve the same masters. Metaphysical speculations about how innocent people can be convicted of crimes that they didn’t commit and the specific railroading of one hapless individual into the death penalty — later commuted to life imprisonment — are certainly related subjects. But the general should grow out of the particular rather than the other way around, and too many threads in Morris’s tapestry raise other questions — like motive — that his movie never addresses, but still can’t expel.

Because the plot isn’t a fait accompli, as the plot of Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man was (Randall Adams, apparently an innocent victim, is still in prison for the murder) the film’s soul-searching about fate overrides too many practical matters and issues, which it drops and kicks out of sight. One understands the technical problem: the necessity of making an endless jumble of facts lucid, legible, entertaining, on some level betrays its obscurity, its illegibility, its intransigence. Reaching for poetics to justify this obfuscation is understandable but dangerous. In the work of Werner Herzog, Morris’s mentor and principal influence, this has led to some of the worst excesses of German romanticism disguised as documentary and/or poetic truth — most recently, in Herzog’s Cobra Verde (according to some reports, a glorification of slave trading).

7. To cite a much greater film than The Thin Blue Line that doesn’t display the same kind of contradictions, I happen to find Shoah “entertaining” in a fashion as well. It might seem indecent to refer to a 503-minute nonfiction investigation into the Holocaust as “entertaining”; I certainly don’t want to imply that the film isn’t full of pain and sorrow, but let’s consider a hypothetical situation: a Jewish man who has lost most of his family in the Nazi concentration camps is watching all eight hours of Shoah. Most of us wouldn’t dream of calling this “escapism.” But it’s entirely possible that the man who is watching Shoah is so involved in the experience that he is forgetting all sorts of things that he might otherwise be concerned with: his hay fever, his problems at the office, his irritation about George Bush, his ailing spouse. Shoah certainly compels the viewer to think; as a complex statement that stages a dialectical encounter between existentialism and Judaism, the present and the past, it obliges us to reflect on the Holocaust in a way that many of us never have before.

But it’s only the use of “entertainment” in our vocabulary as a puritanical censoring device that arbitrarily isolates the experience of Shoah from the experience of being entertained at the movies. After all, Shoah is only a more concentrated, extended, and serious version of what we’re asked to think about in a “pure” movie like Judgment at Nuremberg. Why should the fact that Shoah performs this task infinitely better than Stanley Kramer’s movie, without the benefit of Judy Garland, deprive us of the validating term “entertainment”?

8. The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), directed by William Wyler, is a good example of how the postwar 40s dealt with the challenge of bearing witness to a social reality and entertaining an audience at the same time. The mesh of strategies isn’t a perfect fit, and much of the film trails off into mystifications about what happens to armless veterans, for instance, but at least the 40s audience was willing to accept the results as a movie and a film at the same time. In the case of George Romero’s recent Monkey Shines, the mass audience got scared away from one of the purest movie entertainments of the year because the hero is a quadriplegic, and quadriplegics by (puritanical mis-) definition are incompatible with entertainment — unlike heroes who have two broken legs, like James Stewart in Rear Window. It sounds crazy and it certainly becomes self-defeating, but the very word “quadriplegic” makes Monkey Shines sound like a film rather than a movie to people who haven’t seen it. Even quadriplegics themselves aren’t amused, to judge from reports of a protest by quadriplegics against the movie’s trailer in Los Angeles — which suggests that practically everyone seems to agree a priori that quadriplegics and movies don’t mix. Consequently, one of the year’s most effective entertainments gets treated like a leper.

9. On the other hand, an alleged “film” like Wings of Desire is chock-full of old-fashioned movie pleasures, from ethereal flights over Berlin to Peter Falk’s gutbucket voice and husky charisma, and audiences don’t seem to mind at all. The movie doesn’t even ask us to think very much — less, say, than The Last Emperor, another good example of crossover between film and movie that doesn’t scare an audience away. But the best cover of all for a filmmaker who wants to do something adventurous and “filmic” is to hide behind a foolproof package, as director Renny Harlin does in A Nightmare on Elm Street 4. As long as there’s no apparent threat that anything “serious” is being attempted, a filmmaker is free to do anything at all — in this case, put together a film that is little more than a nonnarrative string of dreams.

10. Entertainment implies that only one part of the brain is being used. Secretly, I suspect, all of us would rather be enraptured than diverted, and shaken up rather than soothed, but supposedly, goes the received wisdom, there’s something “safer” about mild diversion- – even if it eventually becomes a bludgeoning form of oppression. Imagine drowning in a sea of Perry Comos and you’ve got the 50s and its taste for tranquilizers down to a tee. Or think of Ronald Reagan, who wouldn’t be caught dead in a film and has managed to catch us all, dead as doornails, at the movies. But as soon as we reduce our possibilities to an either/or proposition — art or entertainment, entertainment or edification — we’ve limited our capacities to experience any of them.